Decisions, Decisions

By: Erin Peterson | Categories: Campus News

Every moment of our lives is filled with decisions—some small, some monumental. Should you drive through that yellow light? Is it time to let your company know a colleague is taking liberties with the expense account? How should you choose whether or not to take that life-changing opportunity that’s halfway across the world?In the following pages, we share the insights of eight Georgia Tech experts who understand decision-making at every level, from inside our brains to inside the boardroom. They share the quirky decisions that humans make—and the surprising ones that robots make.

They might not to be able to give you the exact answers you seek, but they just might be able to help you with the process of getting there.

HOW AI HELPS HUMANS MAKE CHOICES AND VICE VERSA

There’s no question that much of the population is looking forward to a world fueled by artificial intelligence. Over the years, we’ve watched Deep Blue defeat chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov, trusted our email software to filter out the most egregious spam and phishing messages, and used Alexa and Siri as our personal assistants. Eventually, artificial intelligence projects powered by companies like Waymo and Uber might allow us all to hand off our driving duties for good. At Georgia Tech, we even pioneered the first AI teaching assistant to help students succeed in class.

Ayanna Howard, chair of the School of Interactive Computing, says such advances have often led us to place greater confidence in robots than maybe we should. Studies have shown, for example, that people will defer to a robot’s faulty suggestion, even in high-stakes situations such as an emergency evacuation. “If they trust them, humans tend to defer their decisions to robots,” she says.

Howard, who has spent her career exploring both the possibilities and limitations of artificial intelligence, says these findings illuminate just how important it is to make sure that machines can make decisions wisely.

There are plenty of cautionary tales about the failings of artificial intelligence, says Charles Isbell, professor and executive associate dean for Tech’s College of Computing. From the well-publicized Amazon hiring algorithm that turned out to have a bias against women, to systems designed to predict an inmate’s recidivism rate that primarily predict race and neighborhood residence, machine learning isn’t always better.

“Computers make us more efficient at making bad decisions just as well as they make us more efficient in making good decisions,” Isbell says.

If humans and machines are imperfect in their decision-making, is there a better option? Isbell says yes. It turns out that humans paired with artificial intelligence can do far better work than either one alone.

For example, teaming a mediocre chess player with a chess AI system creates a chess-playing powerhouse that is better than artificial intelligence or a human grandmaster alone.

"If they trust them, humans tend to defer their decisions to robots," Howard says.

“Machines can simulate millions of moves a minute and imagine futures faster than any person,” Isbell says. “But they can’t necessarily figure out that it’s important to have pieces in the middle of the board or that pawns should be clustered together. Humans can help eliminate a billion useless moves and save an exponential amount of time.”

Howard, meanwhile, says that injecting cold, calculating AI systems with a bit of human empathy can help make them more effective. She knows first-hand from building AI systems to support therapy for children with autism and cerebral palsy.

A therapy program, for example, might ask a patient to move quickly to hit a target on a screen. If the patient only partially completes the task, he or she can still get a bit of positive reinforcement from the robot along with helpful guidance. “The machine might say, ‘Great job, you hit one of the targets! Next time, move a little faster,’” she explains.

If the guidance works, the machine learns the appropriate form of interaction and tucks that information away for later use. If it fails to evoke the anticipated reaction, it can go back to the figurative drawing board.

In the end, Isbell says, diversifying our intelligence by making the most of both human perceptiveness and raw computer power can accelerate our progress on some of society’s most vexing problems.

“Human and AI strengths complement each other, and our weaknesses complement each other,” he says. “Decision-making is better when we combine those completely different strengths.”

UNDERSTANDING THE PSYCHOLOGY OF HIGH-STAKES DECISION-MAKING

If you go to the doctor’s office with a laundry list of mysterious symptoms, your doctor is likely to choose a medical test or two to help zero in on a diagnosis. You might reasonably assume that those test suggestions are based on his or her careful, logical assessment of the information you provided.

But according to research done by Tech Associate Professor of Psychology Rick Thomas, doctors—just like the rest of us—are influenced by what are known as primacy and recency (bias) effects. “The first few pieces of information and the last few pieces of information tend to have a greater influence on diagnostic behavior than information that happened in the middle of a sequence,” Thomas says.

The stakes for such basic psychological quirks turn out to be surprisingly high when it comes to making medical decisions: That unequal weighting may lead to less useful test suggestions, a longer timeline to a successful diagnosis, and higher costs to patients who need more testing.

"A deeper understanding of what is influencing test selections may help scientists develop processes that allow doctors to choose more wisely," Thomas says.

Thomas serves as director of Tech’s Decision Processes Lab, where he and his team use eye tracking, EEG and statistical modeling to understand how experts in high-stakes professions—including doctors, intelligence analysts and pilots—make decisions. He and his researchers also develop tools to help people and AI systems arrive at better choices.He says that the more we understand what influences a person’s decision-making, the better chance we have of seeing and correcting errors.

In the case of doctors and test selection, a deeper understanding of what is influencing test selections may help scientists develop processes that allow doctors to choose more wisely. “In theory,” Thomas says, “that might mean creating a decision-support system, such as an artificial intelligence agent that could help give doctors advice.”

HOW YOU CAN MAKE BETTER DECISIONS WHEN EVERYTHING'S ON THE LINE

Rick Thomas says three rules of thumb can help us make the right decision when it counts the most.

1. Give yourself time. It turns out that there really is some scientific validity to sleeping on a tough decision. “With more time, you’ll end up generating a richer set of alternatives than if you make a snap judgment,” Thomas says.

2. Stay focused. Big decisions demand that we make the most of our brain power, so try to tackle your toughest decisions when there aren’t countless other distractions competing for your attention.

3. Take another’s perspective. In group decision-making, like work projects, it’s easy for people to take their own priorities into account first. When you can take the perspective of someone else in your group who might have different interests, you might come to a different conclusion. “It’s an approach that helps you think about a problem in a different way,” he says.

MAKING ETHICAL CHOICES TAKES BRAVERY

From Facebook’s shady political dealings to the many #MeToo coverups that have been brought to light after percolating for decades, there’s no question that many businesses and leaders need to make some ethical overhauls before their unscrupulous deeds or policies catch up to them.

It’s easier said than done, says Steve Salbu, Cecil B. Day Chair in Business Ethics and former Scheller College of Business dean. “Business incentives can create cultures where employees aren’t comfortable reporting ethical lapses—or are ill-equipped to do so,” Salbu says.

Without protections in place, whistleblowers can lose their status, miss out on future opportunities, or even get booted from their jobs. Often, it’s easier just to decide to go with the status quo rather than to stand up for what’s right.

"Being ethical often takes courage," Salbu says."If it were easy, most people would always do the right thing, but with pressures that encourage unethical behavior, doing the right thing requires bravery."

Similarly, employees might let their ethical code slide if a fat bonus is on the line, or if they see fellow coworkers making ethically dubious choices. “Being ethical often takes courage,” Salbu says. “If it were easy, most people would always do the right thing, but with pressures that encourage unethical behavior, doing the right thing requires bravery.”

WHY START-UP INNOVATORS STRUGGLE WITH BLIND SPOTS

As a whole, entrepreneurs are a bright and remarkably perceptive group. But after years of working with them, Merrick Furst, distinguished professor in the College of Computing and the founding director of Tech’s Center for Deliberate Innovation, uncovered a surprising truth: Almost all of them had blind spots that were sabotaging their businesses.

“If you notice you have an important decision to make, for example, you can work on it. There are probably lots of tools available,” he says. “But what if you don’t even notice that decision point in the first place? People don’t notice that they’re not noticing something.”

“Not noticing that you’re not noticing” sounds like a brain-twisting Zen koan. But Furst says illuminating those dark corners of entrepreneurial attention is essential. Too often, entrepreneurs are focused on common problems—make a product, find a customer, raise money—but don’t realize that they need to solve a far bigger issue, such as discovering a truly authentic demand for a product or service.

So how can entrepreneurs (or any of us) begin to notice all of the important things that have flown under the radar?

It starts, says Furst, by building a culture designed to pick up on things we might otherwise miss. He compares the process to working in a woodshop. “You might not notice that you’ve forgotten to measure things before you cut them if you’re in the kitchen” he says. “But if you’re in a woodshop—where there are signs that say ‘measure twice, cut once,’ where there are rulers everywhere, and where you’ve hopefully had some training—you’ll probably remember to measure before you cut.”

Creating a culture that focuses on finding blind spots is similar to creating that woodshop.

It’s advice that perhaps we all could take, whether we’re trying to launch a new venture or not. Uncovering your own blind spots may be as simple as asking someone to share their candid assessment of how you are thinking, if you (and they) can bear it. “Assume they’re being reasonable,” Furst says. “A practice like that is much better than doing nothing at all.”

HOW NOT TO MAKE AN IMPORTANT DECISION

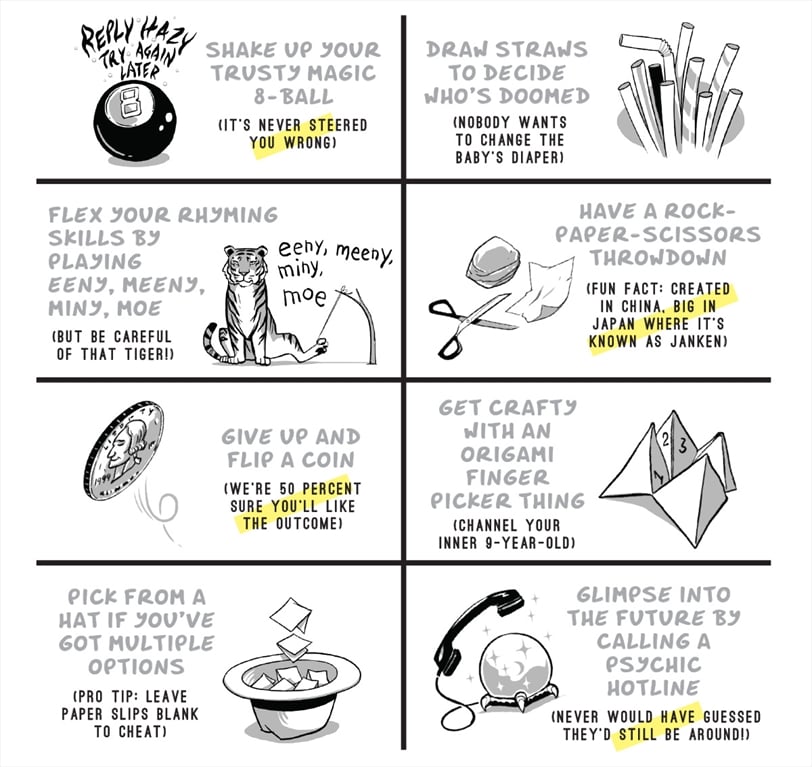

A Comic By Roger Slavens | Illustrations by Charlie Layton

Sometimes it may seem nigh impossible to make an extremely critical choice in life. Like whether you should switch careers (give up the cushy desk job to go on the professional karaoke circuit?). Or where you should take the family on holiday (wintering in Greenland to score those sweet off-season deals?). Or who gets the last slice of Hawaiian pizza (we hope it’s not us—seriously, pineapple on pizza?). But Georgia Tech experts agree that no matter how tempted you are to shirk your responsibility or indulge your superstitious nature, you shouldn’t use any of the following methods when the stakes are truly sky high.

3 WAYS THE BRAIN WORKS TO MAKE CHOICES

1. HOW MEMORY PLAYS A ROLE

Plenty of our memories are easy to retrieve without a moment’s hesitation: a first kiss, a major achievement, where you were on 9/11. But other memories take time to retrieve. Who was the vaguely familiar person who said hello to you at the grocery store last night? What did you have for dinner two days ago?

As you sift through context clues to figure out the answer—you might not remember that two-days-ago dinner, but do recall that you went to a movie that night, so maybe you reheated leftovers, like pizza?—your brain will see increased activity in areas including the inferior temporal, frontal and parietal regions, according to the research of Tech Professor of Psychology Mark Wheeler.

Once those regions reach a certain level of activity, you’ll also feel a sense of recognition that persuades you that your memory is correct. (“Yes, it was definitely pizza.”)

“When we’re deciding if a memory is accurate, we might have a very strong sense of something that’s accompanied by lots of detail, and sometimes it just ‘feels’ like the right thing,” Wheeler says. In other words, that feeling of confidence is more than just an ephemeral emotion: It’s determined by very real activity in the brain.

2. THE PERFECT MENTAL STATE FOR SNAP JUDGMENTS

To make good, quick decisions in uncertain environments—whether or not to drive through that yellow light, for example—it’s important to be paying just the right amount of attention to the appropriate things.

Deep in our brain’s cortex, we have a mix of excitatory and inhibitory neurons that help us do that. “These neurons are connected to each other, and there’s a constant interplay between them to keep things in an optimal state,” says Bilal Haider, assistant professor of bioengineering.

So if you’re driving home from work on autopilot one evening, you might see a stoplight turn yellow and hit the brakes, even if you could have easily made it through. Perhaps you’re simply in a low-attention state where you don’t feel the urgency to make a quick decision. The next day, however, you might be driving the same route and hit the same yellow light—but you know you’d like to make it home to catch the tail end of a football game on TV. So you’re paying attention closely and safely sail right through the light. “The only thing that’s different is the context in your brain that says you need to detect and respond to the stimulus in one way one day, and another way on another day,” Haider says.

You might be able to imagine a third scenario in which you’re driving a friend who’s in labor to the hospital. She’s anxious, you’re anxious, and you might be too agitated to make a good decision about an otherwise easy call on that yellow light.

For Haider, the point is that balance is essential in certain types of decision-making. “There’s a sweet spot in the middle where you’re calm and alert,” he says. “You’re not too disengaged to act, but also not paralyzed by the consequences. Because those two extremes are when the decision-making suffers.”

3. DECISION-MAKING MISTAKES MAY SIGNAL ALZHEIMER'S OR OTHER DISEASES

To understand how brains work during the decision-making process, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering Annabelle Singer sends rats through mazes and measures their brain activity. After successful runs, the rats tend to show specific patterns of neuronal activity in their hippocampus that suggest that they are “replaying” their route. They encode it into their brains so that they can remember the right choice to make at every fork in the path.

As the rats get better at knowing the best routes over time, Singer and her team see these same neuronal patterns in the rats before they start a successful run—suggesting that they may be “pre-playing” the successful route.

Because rats’ and humans’ brains share so many similarities, Singer’s work is helping shine a light on how decision-making works in humans—and what it might tell us when things go awry. We’re not navigating mazes, but we do have to make our way around the world every single day—and when that goes off track, there may be a specific area in the brain we need to be paying attention to.

“The hippocampus is implicated in many different diseases, including Alzheimer’s,” Singer says. “And one of the first symptoms of Alzheimer’s is that people get lost in a familiar place.”

Singer’s work may help us pinpoint the brain-linked glitches that signal bigger problems—and help develop treatments that can make an impact before a disease has progressed.