Shane Kimbrough: Life on the International Space Station

By: ROGER SLAVENS | Categories: Alumni Association News

Shane Kimbrough: Life on the International Space Station

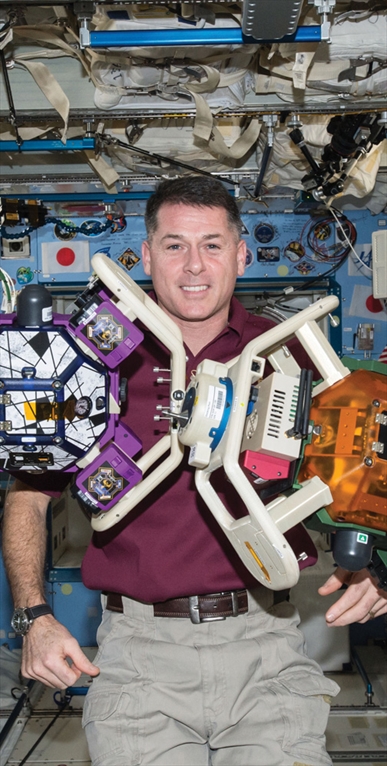

Youthful dreams of donning spacesuits and piloting rocket ships propelled most astronauts into their professions. But it’s their grown-up expertise in science and engineering that allows them to punch their tickets out of this world. Just ask NASA astronaut and Georgia Tech alumnus Shane Kimbrough, MS OR 98, who recently spent six months as commander of the International Space Station. He shares what living and working in space is really like—and what it took for him to get there.

RIGHT NOW, SOME 250 MILES ABOVE EARTH, the International Space Station (ISS) hurtles through the heavens at nearly 17,500 miles per hour—just as it has for nearly two decades. It’s hard for most of us to fathom that traveling at such a breakneck speed could result in anything short of disaster. Yet the station’s motion is relative, and the crew members onboard float along in microgravity unfazed, going about their daily routines as the ISS continues its ceaseless, frictionless orbit around our planet.

RIGHT NOW, SOME 250 MILES ABOVE EARTH, the International Space Station (ISS) hurtles through the heavens at nearly 17,500 miles per hour—just as it has for nearly two decades. It’s hard for most of us to fathom that traveling at such a breakneck speed could result in anything short of disaster. Yet the station’s motion is relative, and the crew members onboard float along in microgravity unfazed, going about their daily routines as the ISS continues its ceaseless, frictionless orbit around our planet.

Shane Kimbrough believes the station is the most peaceful place he’s ever visited. Serving as the commander of the ISS for a recent six-month mission, Kimbrough found himself drawn frequently to the observation module known as the Cupola, where he could marvel at the 360-degree panoramic views outside the station, especially its constant vigil on the Earth below.

The Cupola hasn’t always been a fixture of the ISS. For more than a decade, inhabitants of the station were afforded a rather poor glimpse of their celestial surroundings. The smattering of portholes and small windows throughout the station’s modules provided astronauts little perspective on their trajectory through space. To fix this design flaw, the Cupola was added in 2010, giving the ISS seven new windows on the cosmos.

“It’s a spectacular place to sit and think,” Kimbrough says of the Cupola. “Looking down upon the Earth is mesmerizing. Our planet is just so serene and strikingly beautiful. And if I sat there long enough, I could see virtually all of it, from the ice shelves of the Arctic Circle to the deserts of Africa to the reefs of Australia.”

But it’s what Kimbrough couldn’t see from this perfect perch that truly resonated with him. “From this vantage point, I couldn’t see the wars going on,” he says. “I couldn’t see any signs of conflict even though I knew it was there. It made me wish everyone else could see our world like this and realize what a gift we have and need to protect.”

Many of us grew up dreaming of becoming astronauts, setting out to escape the bounds of Earth and explore the depths of space in high-powered rockets. However, except for a determined, lucky few, we inevitably gave up this flight of fancy for more practical pursuits—namely because we thought the opportunity to launch into the heavens was completely out of our reach.

For Kimbrough, however, the dream was closer at hand. Much closer.

He was born in 1967, right in the middle of the great space race between the United States and the Soviet Union—and just as mankind was reaching for the moon. “When the Apollo missions were launching, the whole country stopped whatever they were doing and watched,” Kimbrough says. “It’s different now, but I think everyone my age wanted to be an astronaut. I just had a little more of that desire in my blood.”

Part of that interest and desire grew from his opportunity to watch numerous rocket launches up close and in person as a young child. His grandparents’ house was located right across from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and Kimbrough even lived with them for a spell while his father, a career officer with the U.S. Army, served in Vietnam.

“When I was living there or visiting on vacation, my grandfather took me there to see everything that launched at Cape Canaveral—the Apollo rockets, satellites, everything,” he says. “It was so exciting to be a kid and to see them all blast off.”

He didn’t know it at the time, but in just a few decades, it would be Kimbrough himself who would blast off into the cosmos as a NASA astronaut. He’s since visited space twice: once on the Space Shuttle Endeavour mission STS-126 in 2008 (alongside fellow Tech alumni Eric Boe, MS EE 97, and Sandra Magnus, PhD MSE 96 ) and more recently via a Russian-built Soyuz spacecraft that launched in October 2016. Both times he was bound for the ISS.

ALL ABOUT THE ISS

The ISS is a joint project of five space agencies: NASA, Roscosmos (formerly the Russian Federal Space Agency), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). The station’s primary function is to serve as a microgravity (read: weightless) and space-environment research facility, as well as a place to test spacecraft systems and equipment for demanding future missions to places such as Mars.

Launch and assembly of the ISS began in 1998, and it took 10 years and more than 30 international missions to construct the modular station as it’s configured today. The ISS was built in orbit, piece by piece, using robotic equipment and spacewalking astronauts from Soyuz ships and NASA shuttles, and eventually, once habitable, from the station itself. It’s scheduled to get even larger, as two new modules—designed to accommodate larger crews and commercial spacecraft—are scheduled to be added by 2019.

The ISS measures roughly the length of an American football field, including end zones, and weighs more than 430 tons. It’s composed of 16 different pressurized modules and connecting nodes that contain living quarters (sleeping cabins, a kitchen, a gym, two bathrooms) for the crew, as well as laboratories, power and life-support systems, the Cupola, docking ports and other facilities.

The first humans to reside on the station were NASA astronaut Bill Shepherd and Russian cosmonauts Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev in 2000. The ISS now accommodates up to six full-time crew members at once.

Kimbrough affectionately calls his first visit to the ISS aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour less than a decade ago the “home improvement” mission. “Our goal was to help expand the crew area, and we brought and installed a new bathroom, a new kitchen, a new gym, and new bedroom,” he says. “Shuttle missions only last about two weeks, however, and we were only docked to the station for 10 days or so. We got a lot of it set up but not everything was functioning when we left. When I came back to the ISS some eight years later, it was neat to see all these areas working and also get a chance to use them for six months.”

TIME TO TRAIN

A few years after his Space Shuttle mission, Kimbrough was visiting the Kennedy Space Center when he got the call asking him if he wanted to go back into space and serve on ISS Expeditions 49 and 50. His answer was an instant and resounding “Yes!” Kimbrough’s administrative duties at NASA were interesting and challenging, but spaceflight was the reason he became an astronaut.

That thrill quickly turned to resolve as his two-and-a-half years of mission training—much of it spent in Star City, Russia, home of the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center—began. “I had to travel to Star City four to five weeks at a time because the only vehicle we have to travel to the ISS right now is a Russian spacecraft,” he says.

This new schedule proved to be a challenge for Kimbrough, his wife Robbie, and their three children. The family lived in the Houston area not far from the Johnson Space Center, but Star City was nearly 6,000 miles away.

“It took a while to get into the flow with my family of the here-a-month, gone-a-month, then-repeat routine,” he says. “Luckily, they knew what a special opportunity this was for me and they were incredibly supportive. Robbie already knew full well what the life of a military officer and an astronaut demands of a family.”

As you might suspect, training in Russia on Russian spaceflight systems requires a considerable command of the Russian language.

“Astronauts have to be at a certain fluency level before NASA will ever consider assigning you to a mission,” Kimbrough says. “That’s because once you’re in that spacecraft, everything is in Russian—the displays, the computers, the checklists, the communications from mission control in Moscow. You’re not learning how to ask ‘Can I have a cup of coffee?’ It’s very challenging and technical, and it uses a completely different and difficult alphabet (Cyrillic), too.”

In addition to learning the language, Kimbrough had to adapt to the Russian style of training. Safe to say, it was even more intimidating than earning his master’s degree at Georgia Tech.

“You’d study and train on all the systems and equipment, and then they’d hit you with exams,” he says. “They’re particularly big on oral exams, and you have to be prepared to sit in front of a committee of experts who will hammer you with questions. It was scary at first. They like to yell a lot. But you get used to it. It’s just the way they do things. And then after you’ve passed an exam, you’re debriefed and you all go out to socialize together.”

Final exams are particularly brutal, and Kimbrough had to go through them twice—the first time as a member of the backup crew for the preceding expedition and the second just weeks before his scheduled launch. “These last tests take two full days, back to back, one in the ISS trainer and then one in their Soyuz spacecraft,” he says.

After Kimbrough and his fellow crew passed, then came the pomp and circumstance.

“They’re really big on formal ceremonies here, so the next day we traveled down to Red Square in Moscow and visited the gravesite of the first man in space, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, and then we went to the Kremlin,” Kimbrough says. “The Russians are a warm people and very proud of their space program, so it turned out to be an amazing, emotional experience that made me feel like I was part of the country’s history.”

SHANE KIMBROUGH: A CAREER IN SPACE

Full Name: Robert Shane Kimbrough

Full Name: Robert Shane Kimbrough

Birthdate/place: June 4, 1967, in Killeen, Texas

Family: Married to Robbie Lynn (Nickels) Kimbrough; they have two daughters and a son.

Education: Graduated from The Lovett School in Atlanta in 1985; earned a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering in 1989 from the United States Military Academy (West Point) and a master’s degree in operations research in 1998 from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Military Experience: Commissioned as Second Lieutenant in U.S. Army in 1989 and entered U.S. Army Aviation School; designated Army (helicopter) aviator in 1990; assigned to 24th Infantry Division in Fort Stewart, Ga., then deployed to Southwest Asia and served in Operation Desert Storm; in 1994 was assigned to the 229th Aviation Regiment at Fort Bragg, N.C.; after completing graduate school at Georgia Tech, became assistant professor of mathematical sciences at West Point. He retired as colonel in the U.S. Army.

NASA Experience: Joined Johnson Space Center in 2000 as a flight simulation engineer; selected as an astronaut candidate in 2004; completed astronaut candidate training in 2006; between missions has served in a variety of capacities, including chief of the Vehicle Integration Test Office, as well as chief of the Robotics Branch for the Astronaut Office.

First Spaceflight: 2008 Space Shuttle Endeavour mission STS-126 to International Space Station; helped expand living quarters to accommodate six-member crew on the ISS; logged nearly 16 days in space, including two spacewalks.

Second Spaceflight: Commander of ISS Expedition 49/50; launched into space on Oct. 19, 2016, returning six months later on April 10, 2017; completed four spacewalks (totaling 26 hours).

Total Time in Space: 189 days (so far)

THE ROAD TO LIFTOFF

After a few days off to relax, the time came to travel to the Baikonur Cosmodrome, the world’s first and largest spaceport, located on the steppes of southern Kazakhstan. This is the place that the Soviets sent the first satellite, Sputnik, into space.

“We flew over on two of these giant, old-school military planes,” Kimbrough says. “The planes were just full of people—all our trainers, engineers and support staff came with us. You can’t take a commercial flight there to Baikonur. There’s only one way in and one way out. To be safe, the prime crew flew on one airplane and the backup crew on the other.”

Arriving two weeks before launch, Kimbrough and a great number of his teammates went straight into quarantine at the large complex. “Mission control didn’t want us to get sick or injured and otherwise compromise the expedition,” he says.

Eventually, the crew’s families and other guests joined them in Kazakhstan. “We each got to invite about 15 people to see the launch,” Kimbrough says. “It’s an expensive trip, so a lot of folks can’t make it, but it’s a treat for those who could. My wife and kids came over, of course. Everyone had to pass their medical screenings before they could get into the facilities. Even then, my interactions with my family were very limited.”

Finally, launch day arrived—Oct. 19, 2016—a month later than planned due to technical difficulties. Considering all they went though and the added delays, it was none too soon for Kimbrough and his two cosmonaut compatriots, Sergey Ryzhikov and Andrey Borisenko.

“Launch day was a crazy day,” Kimbrough says. “We got up, were put through a battery of unpleasant medical tests and ate breakfast. Then, once again, came the ceremonies. All the crew members gathered with their spouses, and we were joined by NASA and Russian officials for a series of toasts.”

Kimbrough got a few minutes to be alone with Robbie, but he wasn’t allowed to hug or kiss her—again for fear of picking up a bug and carrying it up into the closed environment of the ISS. “All the precautions were a little extreme, but I understood,” says Kimbrough, who served as the expedition’s de facto medical officer.

A few more ceremonial acts later, and the crew was taken from quarantine to facilities near the launch pad where they donned their spacesuits. Then the goodbyes continued.

“They sat us down at a table right across from our families—still separated by glass—and we got talk to them through microphones,” Kimbrough says. “It lasted another 45 minutes, which was way too long. I just wanted to get on the vehicle and fly; we had already said our goodbyes several times.”

Three hours before the scheduled liftoff, the prime flight crew was finally given the thumbs up and sent to the launch pad. “They took us by bus to the Soyuz rocket, where we rode up an elevator to the spacecraft, stepped aboard and got strapped in for the flight,” Kimbrough says.

When the countdown came and the engines ignited, Kimbrough was surprised by how smooth the takeoff and ride turned out to be. “The Soyuz rocket and spacecraft are much smaller than the Space Shuttle’s configuration and produced far less turbulence,” he says. “It was super easy, super smooth, all the way up. And those nine-and-a-half minutes it took to get into space went by quickly.”

ARRIVAL AT THE ISS

Normally, after reaching low-Earth orbit, it takes about six hours to travel to and dock with the International Space Station, Kimbrough says.

“Unfortunately, we had to take our time to get there,” he says. “But we knew that going in. We were just the second flight of this upgraded [Soyuz MS series] spacecraft and Moscow Mission Control wanted to test all the new hardware and software changes. So we orbited the earth for a couple days before heading for the ISS—it was tough being cramped in there.”

The docking process proved to be relatively fast, but despite their eagerness to board the ISS, Kimbrough and his crewmates couldn’t leave their confines immediately. “We had to wait about two hours for the pressure to equalize before we could open the hatches and set foot on the station,” he says.

The first half of ISS Expedition 49 was waiting for them. Russian cosmonaut Anatoli Ivanishin, NASA astronaut Kathleen Rubins and Japanese astronaut Takuya Onishi had arrived at the station in July 2016 as the second half of Expedition 48, and the trio had been on the ISS by themselves since early September.

“They threw us a party right off the bat,” Kimbrough says. “They also had everything set up for us to conduct media interviews and talk to our families back in Moscow and Houston. Robbie and our kids had already returned home to the States and they got to see me from the Johnson Space Center.”

DAY-TO-DAY LIFE IN SPACE

It took Kimbrough and his crewmates a little while to get into the swing of things onboard the ISS. The first step was adjusting to microgravity. “It takes time to orient yourself to the physics of weightlessness,” Kimbrough says.

The new arrivals also had to get caught up to speed by the existing crew, who were already preparing for their return flight to Earth, which would take place about a week later on Oct. 30. And they had to adjust to the new regimen of daily duties and routines on the space station.

The workday on the ISS is 12 hours long, from 7:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., Kimbrough says. “And there’s a stopwatch of sorts tracking your progress when you’re working, a literal red line that you have to stay ahead of,” he says.

Every morning, the alarm sounds at 6 a.m. “You have about an hour and a half to clean up, get breakfast and prepare yourself for the day,” he says. “Then at 7:30 a.m., we’d usually start with a conference call with the various Mission Control centers located around the world to discuss the day’s priorities and get any updates we needed. They’d last about 10-to-15 minutes unless something important had come up.”

The crew spends roughly half of each workday—about six hours—conducting scientific experiments for researchers back on Earth. “We’re basically their glorified lab technicians,” Kimbrough jokes.

The rest of the time is split between maintaining the station and the equipment, conducting interviews with media, and exercising and eating. “On very special days, we might have a spacewalk or dock with a ship or satellite,” he says.

After punching the clock at 7:30 p.m. at the end of the workday, the crew grabs dinner and enjoys some free time. Lights out is at 10 p.m.

“We all sleep at the same time,” Kimbrough says. “There’s no one up manning the station or taking the night shift, so to speak. Our Mission Control teams do that job for us, making sure all systems are fine while we rest. They’ll wake us up if there’s a problem, but there rarely is.”

Every astronaut gets a bedroom, if you can call it that.

“The sleep stations are about the size of a phone booth, only not as tall,” he says. “These cabins are laid out in kind of a circle, one on each sidewall, plus one on the ceiling and one on the floor. Remember, without gravity, there’s no true up or down in space.”

Because of that, crew members do tuck themselves tightly into their sleeping bags, which are attached to the walls. “You zip yourself up to keep from ‘sleep-floating’ around the ISS at night,” Kimbrough says. “Some people like to put a bungee cord around their arms or knees to stay in a good sleeping position all night long.”

Daily hygiene also takes some getting used to.

“We have two bathrooms on the station, one in the U.S. module and one in the Russian module, and you have to learn to share just like you would with family,” he says. “But there are no showers. We haven’t figured out how to do that one yet—water loose on the station would be a disaster—so we use washcloths to wipe down in the morning or after exercising. There’s no dirt onboard so we’re really just washing away our workout sweat for the sake of the other crew. Smell does travel in space, at least aboard the station.”

“We have two bathrooms on the station, one in the U.S. module and one in the Russian module, and you have to learn to share just like you would with family,” he says. “But there are no showers. We haven’t figured out how to do that one yet—water loose on the station would be a disaster—so we use washcloths to wipe down in the morning or after exercising. There’s no dirt onboard so we’re really just washing away our workout sweat for the sake of the other crew. Smell does travel in space, at least aboard the station.”

There’s an area outside each bathroom that is designed so that crew can brush their teeth, shave and wash their hair (with dry, rinseless shampoo, of course). “We have a wall with a bunch of Velcro stuck to it so each of us can stash our travel kits and all our personal hygiene gear,” Kimbrough says. “To hold ourselves stable when we’re shaving and getting ready, we stick our feet into some special anchored loops.”

Special leg restraints also come handy when astronauts use the bathroom toilets, which work like vacuum cleaners that suck waste into the commode. Each crewmember even has their own personal urinal funnel that is attached to a hose system.

EATING & EXERCISE

Kimbrough admits that the food on the station was far better than he expected. “It’s come a long way since my Space Shuttle mission,” he says. “The variety is very good, and when you’re cooped up for so long, that variety is key.”

It helped that the crew members hail from different countries with very different cuisines.

“The Russian food, in particular was very tasty, very different than American food,” he says. “I made a point to go down every Friday night to the Russian module to eat with them, and they often would come return the favor on Saturday night. I was also lucky enough to fly with Japanese and French astronauts, and their food was fantastic as well.”

Dining on the ISS isn’t far different from what you’d experience on a long-term camping trip. There’s plenty of food onboard and most of it won’t spoil. Some of it comes in dehydrated packages, with the food needing liquid to be added while it’s cooked over heat. Meanwhile, other food is ready to eat, like cookies and fruit. The station has an oven, but no refrigerator. Spices are available, but primarily in liquid form since stray salt or pepper grains could wreak havoc with the station’s sensitive systems.

Whenever a new supply ship docks at the ISS, it’s the source of big excitement for the astronauts—because it means fresh food. (Shipments arrive every few months.) Once, Kimbrough got to supplement the fresh offerings with lettuce he grew for an experiment, though it amounted to just a small salad that was shared among the crew.

The crew cooks and eats three regular meals daily. And they’re encouraged to take in the proper amount of calories to fuel their activities and keep their bodies healthy. “For me, I needed to try to consume 3,000 calories a day,” Kimbrough says. “But the portions were so small that I had a problem getting enough, so I had to raid the pantry a lot. It felt like I was eating all the time.”

Like maintaining a generous diet, getting daily exercise is critical for long-term stays in space. “In our early missions to the ISS, astronauts didn’t exercise,” he says. “They really didn’t have any way to work out let alone any equipment. Now we understand that if you don’t exercise, it really messes with the human body. In extended time in microgravity environments, you can lose a lot of bone density and muscle mass.”

For this reason, crew members must exercise for at least two hours a day. That includes cardio work on a treadmill or exercise bike, and resistance training on the NASA-designed Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED). Kimbrough’s Space Shuttle STS-126 mission delivered and installed the ARED, which provides enough resistance equivalent to simulate weight training. (Weight training is virtually impossible in microgravity; what weights 200 pounds on Earth would be no effort to lift on the ISS.)

For this reason, crew members must exercise for at least two hours a day. That includes cardio work on a treadmill or exercise bike, and resistance training on the NASA-designed Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED). Kimbrough’s Space Shuttle STS-126 mission delivered and installed the ARED, which provides enough resistance equivalent to simulate weight training. (Weight training is virtually impossible in microgravity; what weights 200 pounds on Earth would be no effort to lift on the ISS.)

“On the ARED, you can do dead lifts, squats, bench presses, curls, abs and whatever you could do on the ground in a normal gym back home,” he says.

The absence of Earth’s gravity also has other little-known effects on the human body. “For one, in space, the fluid in your body tends to shift toward your head rather than your feet,” Kimbrough says. “That’s why a lot of astronauts look red and puffy-faced during interviews while we’re up there. But it also does get rid of your wrinkles, which is a good thing, I guess.”

Also, with no gravitational compression on his spine, Kimbrough and his colleagues grew taller in space. “My spine expanded a little bit and I finally hit my lifetime goal of topping 6 feet in height,” he says. “Our support teams had to account for this growth when they sized us for our spacesuits back on Earth.”

EXPERIMENTS & COMMUNICATIONS

The bulk of the astronauts’ work duties on the ISS involves conducting scientific experiments. After all, the main reason the station exists is to investigate the effects of microgravity on a variety of scientific disciplines, from biology to physics to technology. The station also provides a unique vantage point for collecting data about the Earth and outer space.

What’s somewhat surprising is that the crew members running this research usually know little about the experiments themselves.

“The projects that we test at the ISS have gone through an extensive vetting process before they make it to space, but it’s impractical and impossible for us to be trained on all of them,” Kimbrough says. “The experiments have been optimized so we can easily follow instructions to conduct them and record the results. Sometimes we get the researcher on the phone to walk us through the process if it’s especially complicated.

“We try our hardest to get the research right, because we know scientists have spent years to get their experiments onto the station. We’re very careful—sometimes things take a little longer than planned, but as long as we get the data they want, it’s well worth it.”

When the work is done each day, the crew enjoys a couple hours of downtime. As much as Kimbrough liked to visit the Cupola to gaze at the Earth, his favorite way to unwind was to connect with his family.

“I got to talk to my wife every day and my kids about three to four times a week,” he says. “On Sunday afternoons, we’d do a video conference weekly. Even though I had two daughters in college and my wife and son at home, the technology allowed us all to interact with each other, almost like we were sitting in the same room together. It was just that mine was 250 miles up in the sky.”

A WELCOME BUT BUMPY RIDE HOME

After six months in space, Kimbrough was ready to go home. “We had a great mission, but we couldn’t wait to return to Earth,” he says.

The day of disembarkment, April 10, 2017, started with a “fluid-loading” protocol where the astronauts drank a lot of liquids and took salt tablets to keep it in their systems. “It helps with your recovery coming back into gravity and you just feel better if you follow the process,” he says.

Everything got packed up, including an official Ramblin’ Wreck flag that Kimbrough had proudly flown on the station, and the crew members put on their spacesuits, got into their respective seats and strapped in to leave the ISS. About an hour later, after all systems were checked, the Soyuz MS-02 undocked from the station and started its controlled descent. It was going to take about three-and-a-half hours for the return trip to where it all started, the steppes of Kazakhstan. And, yes, that meant the landing would literally be a hard one.

“It was a really interesting ride home—very dynamic,” Kimbrough says. “We weren’t under constant stress, but we definitely felt the big events like the explosions that preceded the module separations and the opening of the parachute. Only the crew module survived re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, with the other modules burning up along the way.”

And then the trip abruptly came to an end.

“We crashed into the ground hard—really hard,” Kimbrough says. “We actually rolled a couple times and then got dragged around a bit because the wind played with our parachute. But once all that settled out, the search and rescue forces only took about 10 minutes to find us. None of us were hurt except for some bumps and bruises, thankfully, but we didn’t feel that great either because our bodies were readjusting to the forces of gravity.”

And then the Russian technicians opened the module and helped the astronauts out of the spacecraft.

“It was so amazing to smell fresh air again and to feel the sun on my face,” Kimbrough says. “We had spent six months on the ISS able to see the sun 24/7, but since we were separated from it by layers of glass and insulation and steel, we could never feel its warmth.”

A helicopter ride to a major airfield, a jump on a NASA airplane, and 24 hours after putting his feet back down on solid ground, Kimbrough was back in Houston and in the arms of his wife and kids. He was already starting to feel like an earthling again.