Things New and Strange, an Excerpt

By: G. Wayne Clough | Categories: Alumni Association News

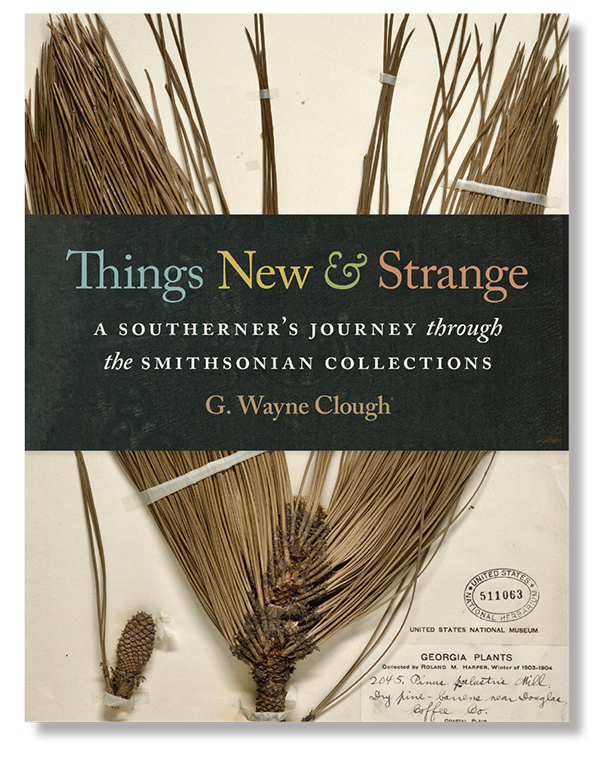

Things New and Strange: A Southerner’s Journey Through the Smithsonian Collections

By G. Wayne Clough, CE 64, MS CE 65, Hon PhD 15, President Emeritus of Georgia Tech and Secretary Emeritus of the Smithsonian Institution

The following is the introduction from a fascinating new book written by Georgia Tech President Emeritus G. Wayne Clough that chronicles a quixotic scavenger hunt he took after retiring from the Smithsonian Institution. As the first secretary of the Smithsonian born in the South, Clough was curious to see what its collections could tell him about South Georgia, where he grew up. Along the way Clough made many surprising discoveries—ranging from animal and plant specimens to cultural artifacts and works of art—that helped him better understand the region from which he came.

One of my first official duties as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution was to be blessed by Buddhist monks. The ceremony took place in a wooden replica of a Buddhist temple, built on the National Mall for the Smithsonian’s 2008 Folklife Festival, which featured the small Himalayan nation of Bhutan. Representing Bhutan at the festival’s opening ceremonies were Prince Jigme Dorji Wangchuck of the royal family and a group of Buddhist monks from a remote mountain monastery. When it was over, the monks told me through an interpreter that they had flown on an airplane for the first time on their trip to Washington, D.C. They said it felt like an out-of-body experience, and as the brand-new Smithsonian secretary, I could relate. But my journey had begun many years before in a small town in South Georgia.

Some may have wondered about my qualifications to be secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, which is the equivalent of being the CEO of a corporation. I could not blame them, because hardly anyone is fully prepared for the diverse responsibilities that come with this position. The Smithsonian is a multidisciplinary enterprise with activities in 140 countries; 19 museums and galleries plus the National Zoo; and nine research centers, including the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, which operates observatories around the world. The Smithsonian serves 30 million visitors a year and reaches about 150 million people through its television channel, magazines, websites and social media. Not to be left out are the collections, which contain more than 154 million objects, specimens, and works of art. And this total does not include its archives and libraries, whose books, documents, recordings, videos and films number in the millions.

"You don’t apply to become the secretary of the Smithsonian; the job finds you,” Clough says.

You don’t apply to become the secretary of the Smithsonian; the job finds you, because someone believes you are the type of person who can preside over an institution that complex and historic. It helps if you like a challenge, feel that you owe a debt to your country, enjoy learning, and are prepared to devote evenings and weekends to the job. Someone believed I was such a person, and the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian agreed. I was the first secretary born below the Mason-Dixon Line.

My home was the small town of Douglas, the seat of Coffee County in southeastern Georgia—far enough south to be closer to Jacksonville, Florida, than to Atlanta, the capital of Georgia. Asked where we were from, my family always said “South Georgia,” a place where the land is flat, often sandy, traversed by slow-moving rivers, and dotted with swamps. To us, North Georgia, although part of the same state, was a different place— home to hills and mountains, fast-moving rivers, and the big city of Atlanta. My first trip through North Georgia did not come until I was 12, when we drove through that part of the state on our move to Chattanooga, Tennessee. I was amazed to see my first mountains and, in the winter, my first snowfall.

When I was growing up in Douglas in the 1940s and 1950s, our schools were segregated; streets such as Grady Avenue, where I lived, were not paved; and most folks who lived on nearby farms, including many of my relatives, had no electricity or indoor plumbing. History books in our schools referred to the Civil War as the War between the States, and a memorial to the Confederate soldier stood at the center of town. It was also a place where a young boy could immerse himself in nature—roaming the pine barrens, exploring the swamps, swimming in the rivers, camping under the stars and learning about flora and fauna through firsthand encounters.

After we moved from Douglas to Chattanooga, I continued my love affair with nature, only now in the surrounding Appalachian Mountains. Geology fascinated me, and I took up spelunking: exploring the caves that were found in the limestone formations. Spelunking led to my studies in geological engineering, first at the Georgia Institute of Technology and eventually at the University of California, Berkeley, where I earned my PhD. I embarked on an academic career and was fortunate to serve as a faculty member and administrator at a number of prestigious universities. At the culmination of my academic career I returned to my undergraduate alma mater, Georgia Tech, as president. As I contemplated retirement after 14 years in that post, fate swooped in, and I was appointed secretary of the Smithsonian. Although some people scratched their heads over the amazing fortune of a small-town boy, it was actually the small town in the boy that served as the anchor throughout the unexpected experiences of a peripatetic life.

As my tenure at the Smithsonian drew to a close, I thought about writing a memoir of my early years, but I realized that others had already done the “Southern childhood” book better than I ever could. However, as I thought about this idea, it became apparent how little I really knew about the place where I had spent my childhood. That’s when it struck me. I was the head of an institution with vast collections that covered natural history, pre-Columbian history, American history, art, culture and just about everything else. Why not explore the insights the Smithsonian collections could provide on the place where I grew up? Like many apparent strokes of inspiration, this one would prove to be a bit like Alice’s rabbit hole—once inside, there was no going back.

The big historical events that shaped our nation barely grazed my hometown of Douglas. So, as I began my quest to learn about my boyhood home from the Smithsonian’s collections, I worried that not much from Douglas or South Georgia had merited inclusion. But this concern showed how little I understood about where I grew up and how much the Smithsonian collections had to teach me.

When I began to search the collections, I was pleased to discover more artifacts connected to South Georgia than I ever expected, and most of them had people tied to them. Usually, people entered the equation with the acquisition of an artifact. Sometimes they were Smithsonian staff who were focused on adding to the collections. But just as often they were unusual people who collected out of love, a desire to learn, a hope they could make money, or a little of all of these things. Collectors can be obsessive and may go to great lengths to find, buy, dig up or even occasionally steal what they want. The portraits, books, landscape paintings and photographs in the history and art collections also tell interesting stories about people. And once artifacts are in the collections, another group of people—curators—takes care of them, organizes them, writes books about them, or makes revelatory findings with them. The people tied to the collections become part of the stories taught by the collections.

Along the way many asked about my project, and I realized that other people might want to undertake a similar search. After all, here was a means to learn about almost anything from a different point of view and an opportunity to experience the surprise and joy of seeing things in new ways. Of course, as the secretary of the Smithsonian I had access to any curator I wanted to ask for help. But I am convinced that the digitization of the collections, which is well underway and proceeding rapidly, offers everyone the opportunity to pursue their own quests through direct online access to objects and documents. The possibilities are unlimited.

A recent concept in our digital world is the Internet of Things. With the development of the cloud and linked digital systems, everything and just about everybody can somehow be linked to everything and everybody else. I learned that the concept of interconnectedness is true when it comes to the Smithsonian collections, if you dig deeply enough. As the great naturalist John Muir said, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” It was this idea that made me realize that my search through the collections was not about understanding what my home in South Georgia was, but rather about understanding how it came to be what it was and why.