Up, Up, & Away

By: Jennifer Herseim | Categories: Alumni Celebrations

Yellow Jacket Flying Club

Formed in 1945, YJFC is the nation's oldest collegiate flying club.

If a Yellow Jacket mascot is not enough of a hint, there are plenty of other signs that Georgia Tech students and alumni are fascinated with flight. In fact, Tech is home to the nation’s oldest collegiate flying club, started by student veterans in 1945.

Jackets have also taken flight in the military—in the most literal sense of the phrase—becoming some of the world’s best aviators.

Aviation and military service have a long history at Tech, beginning in 1917 when the School of Military Aeronautics opened on campus in response to World War I. The U.S. War Department selected several universities, including Tech, to be ground schools for pilots.

Enthusiasm for flying really took off on campus, however, after World War II. In 1945, J.M. Hoffman (pictured below) returned from the war and enrolled at Tech to pursue a degree in architecture. Hoffman approached a professor about starting Georgia Tech’s first flying club, which last year marked its 75th anniversary.

While the pandemic temporarily grounded celebrations, the Yellow Jacket Flying Club (YJFC) plans to host an event to mark the milestone anniversary at the Delta Flying Museum in Atlanta in the spring of 2022.

One of the unique benefits members of Tech’s flying club enjoy is access to club-owned airplanes, says Alec Liberman, YJFC’s president and one of the club’s flight instructors. “Good luck finding another college that owns one airplane, let alone four,” he says. Liberman graduated high school with his commercial pilot’s license, but no previous flying experience is required to join the club.

“We have people of all levels, from alumni who are former Air Force and who want to get back into smaller aircraft to students who have never touched an aircraft before,” Liberman says.

Students, staff, and alumni are all welcome. The one commonality in the group is a shared love of flying.

“It’s a totally different feeling seeing the world from above,” Liberman says.

Mahdi Al-Husseini, PP 18, BME 18, MS CS 2

Army medevac helicopter pilot

“DUSTOFF” PILOTS fly the Army’s elite helicopter ambulances. (Originally DUSTOFF was the term used for casualty evacuation from a combat zone via helicopter.) Their mission is to go anywhere, under any conditions, to transport wounded soldiers from the battlefield to the hospital.

It’s that mission, not the flying (although that’s cool, too), that won over Triple Jacket Mahdi Al-Husseini. He first learned about the mission while he was a student at Tech, interning for the U.S. Army Aeromedical Research Lab (USAARL) in Fort Rucker, Alabama, where he met two DUSTOFF pilots. “They told me about the phrase ‘DUSTOFF, Would Go, ’ and basically, I was hooked,” he says. The phrase comes from a pilot named Charles Kelly, who was killed during a medevac mission in Vietnam. It was his “can-do” attitude that convinced Al-Husseini to become an Army medevac pilot. “No matter the situation, no matter the environment, we do our job to ensure others can live,” Al-Husseini says.

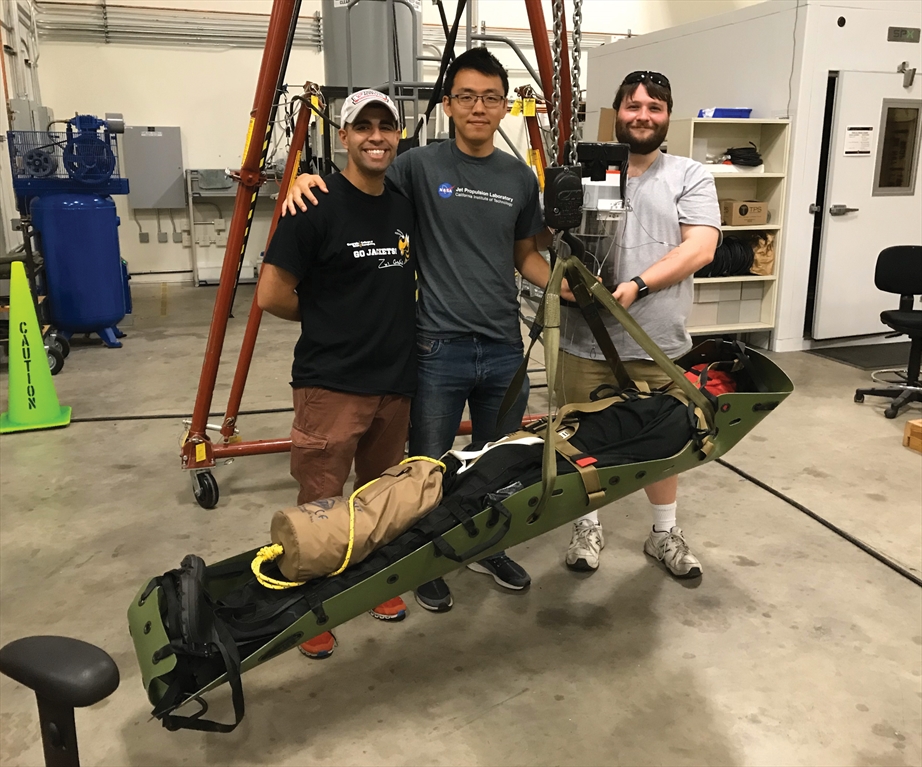

DUSTOFF pilots are expert aviators, who must be ready to fly at a moment’s notice. One of the special operations that they perform is a hoist maneuver. They keep the aircraft hovering while a person is lowered from the back of the helicopter to load a patient onto a stretcher. “It’s a crazy thought, to be honest,” Al-Husseini says. “Any improper input from the controls could result in oscillation, and you could have a person under the aircraft spinning and going up and down.”

Even held steady, downwash created by the rotor blades can cause the stretcher to oscillate. Al-Husseini and his former Tech roommate, Joshua Barnett, Phys 18, invented a device that counteracts this oscillation. The SALUS device attaches between the stretcher and the hoist line and uses reaction wheels to create a counterforce, which stabilizes the stretcher. The device has won several awards and was acquired by Vita Inclinata Technologies earlier this year. Barnett and Al-Husseini have other aviation safety devices in the works, but Al-Husseini is also interested in creating an innovation pipeline between students and Army soldiers.

“There’s a saying in the Army that if soldiers aren’t complaining, something’s wrong. I want to take that innate talent, creativity, and awareness that soldiers have and work with students to help them solve problems.” His unit in Hawaii has begun partnering with students at universities.

Al-Husseini gets his deep commitment to public service from his family and his hometown of Douglasville, Ga. “I’ve had such a tremendous outpouring of support from my family and from my Douglasville community,” he says. “It shaped me. It continues to make me want to give back.”

While he loves flying, his motivation always goes back to public service. “For me, it’s always been about the mission, which at the end of the day is saving people’s lives. Flying, like engineering, is another way to accomplish that mission.”

Jenny Moore, AE 05

Former U.S. Navy Fighter Pilot & Flight Instructor

A failed ride in an F/A-18 Super Hornet was the final confirmation Jenny Lentz Moore needed to become a fighter jet pilot. She was invited to ride in the backseat of the aircraft when she was a Nuclear Power Instructor in the Navy. But just before she and the pilot were set to take off, the ride didn’t end up happening. Standing on Virginia Beach that day, she thought to herself, “Well, apparently the only way I’m going to fly in an F/A-18 is if I fly it myself.”

Four years later, she sat in a Super Hornet—this time in the pilot’s seat. “I remember lining up on the runway and thinking, well here I am. I’m getting my F/A-18 ride finally.” Moore had dreamt of the day since middle school. She was the type of kid who jumped off cliffs into rivers with friends and raced cross-country with her track teammates. “I always wanted to go fast,” she says. But even at top speeds, she knew her feet weren’t meant to stay on the ground.

She applied and was accepted into the Air Force Academy, but in the end, she chose Georgia Tech because of its reputation in aviation and aerospace. “I knew that so many astronauts and aviators had come out of Georgia Tech,” Moore says. “If I wanted to [become a pilot], I knew I could still do it after Tech.”

Moore joined the Georgia Tech track and field team as well as the school’s first female swimming and diving team. Her track team would often run near the Chattahoochee River, close to Dobbins Air Reserve Base. Teammates would tease her because, at the sound of an engine overhead, Moore would stop midrun to search the sky for the plane.

Earning her aerospace engineering degree from the Institute was one of the hardest things Moore says she’s ever done. She learned how to push herself, but also when to get help. “I was the student who instead of agonizing over a lab, I would go to the teacher’s aide and my classmates. I needed that network of resources to survive Tech. That’s served me throughout my entire career and adult life.”

Just as at Tech, in flight school, she put in extra work to learn how to fly. “Some people are natural aviators. I was not one of them,” she recalls. Her perseverance paid off, and in 2013, she joined her first fleet squadron, the VFA-22, also known as the “Fighting Redcocks.”

She flew in combat missions in Syria and Iraq before transitioning from active duty in 2017 and from the reserves in 2020.

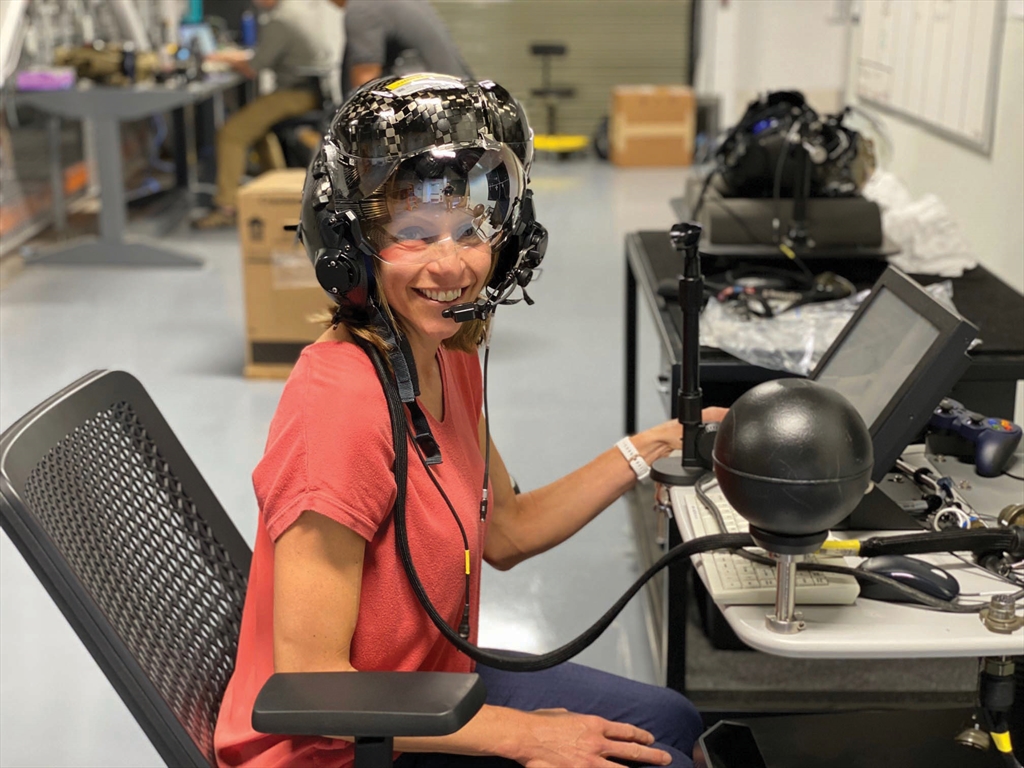

Today, Moore is the training operations manager and lead F-35 instructor pilot at the Marine Corps Air Station Miramar. Teaching pilots how to fly the F-35, one of the country’s most sophisticated aircraft, merges several of her passions. “I love airplanes. I love flying. And I love teaching,” she says.

One thing she does miss from her days piloting fighter jets, however, is the catapult shot that launches fighter jets and their pilots off an aircraft carrier at top speeds. “You go from zero to 150 mph in a very short distance. It’s incredible during the day; it’s terrifying at night.”

Richard Truly, AE 59, HON PhD 09

Former Astronaut and Retired Vice Admiral in the U.S. Navy

A magnet for aspiring aviators and astronauts, Georgia Tech has produced a total of 14 astronauts, including one of the first military astronauts to join the Manned Orbital Laboratory: Richard Truly, retired vice admiral in the U.S. Navy, former fighter pilot, and test pilot.

Truly piloted the Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-2) in 1981 and served as commander of Space Shuttle Challenger in 1983. In a career with an impressive list of highlights, he also served as the first commander of the Naval Space Command; he oversaw the rebuilding of the space shuttle program as NASA’s associate administrator for space flight; and later he led the Georgia Tech Research Institute as vice president and director (1992 to 1997).

Truly and other pioneers in spaceflight inspired generations of future Yellow Jackets to dream of one day becoming an astronaut. But when he was growing up, there was no such thing.

In high school in Meridian, Miss., Truly took the ROTC exam and earned a Navy ROTC scholarship that paid for his education at Georgia Tech. About halfway through his schooling, he decided he wanted to fly.

“The choices then were submarines, surface, or flying. Flying seemed like a great adventure, so I signed up,” he says. “Astronauts hadn’t been invented yet. I had never flown an airplane or flown in an airplane at that point.”

After graduating, Truly became a Navy fighter pilot and then applied for test pilot school.

At the time, the Air Force Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) was starting. Unbeknownst to Truly, his commandant at test pilot school (the famed Chuck Yeager) included the students in Truly’s class as eligible for a position at MOL.

Truly was accepted. He worked on classified missions with MOL until the summer of 1969, when MOL was canceled and he was sent to NASA. “I graduated from Tech and suddenly I found myself at the right age and the right time and it just all fell into place,” he says.

Truly joined NASA between the Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 missions. “At the time, I didn’t really appreciate being part of the historic beginning of the space shuttle program. I was just a kid that wanted to fly. It was fantastic.”

Some parts of flying in space are similar to being in a commercial airplane, Truly says. “In an airplane you look out and here goes Colorado Springs and there goes Denver. In the shuttle, you look out and here goes Italy, here goes Greece.” But then, you’re reminded of the wonder and awe of spaceflight, Truly says.

“I remember the colors of the Earth, the green land and the blue sea and the white clouds. And I remember flying over the Himalayas, which were already snow-covered in November. I remember floating over them. It was just incredible.”