Larger-Than-Life Creations

By: Jennifer Herseim | Categories: Alumni Association News

"Skelly"

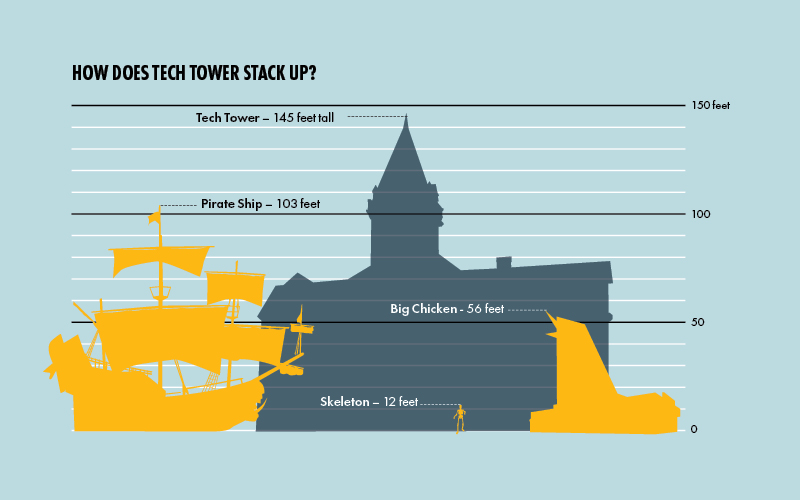

If you needed one more reason to love Halloween, every time you see Skelly, the shockingly tall skeleton that towers over trick-or-treaters in your neighborhood, know that there's a Georgia Tech engineer behind the phenomenon.

Rachel Little, BME 15, is a senior product engineer at The Home Depot, where she works on the company's Halloween and Christmas decorations. Her team was responsible for bringing Skelly to life, engineering the 12-foot-tall skeleton from skull to bony toes.

"A lot of the work I get to do is similar to what I did at the Invention Studio at Georgia Tech," Little says. She reviews 3D-printed models of the products before they move forward with manufacturing and then ship to stores. Often, the trickiest part in the design process is concealing structural frames and making the products withstand weather. "Wind is always the biggest challenge for me," Little says. In 2020, when her senior merchant of decorative holidays came to her and the team with the idea for a giant skeleton, Little thought, "OK, this is a good challenge." Fortunately, Skelly has a lot of bones that wind can pass through.

When Skelly was first released, he sold out within a few weeks. "It was the perfect storm," Little says, "It was the first year of Covid and everyone was stuck at home, so people really leaned into doing exterior decorations." The skeleton's oversized presence brought smiles to people's faces and even spawned its own viral videos on social media, where people shared videos of the skeleton strapped to the top of small cars.

Since engineering Skelly, Little and her team also introduced a 13-foot-tall animatronic Jack Skellington from The Nightmare Before Christmas.

Little's advice for holiday decorating is simple: Have fun with it and don't take it too seriously. "Spider webs and Halloween string lights can go a long way in enhancing your set. And fog. I always love fog."

Atlanta's Skyline

Atlanta would be unrecognizable without the iconic buildings designed by late architect and Yellow Jacket John Portman, Arch 50. His soaring structures include three of the city's tallest buildings: the 47-story Atlanta Marriott Marquis, which was the largest hotel in Atlanta when it was built in 1985; the Westin Peachtree Plaza, which was the tallest hotel in the world when it was completed in 1976; and the Truist Plaza, which at 871 feet is second in height in Atlanta only to the Bank of America Plaza building (932 feet).

The World's Largest Man-Made Whitewater River

For an Olympic kayaker like Scott Shipley, navigating a path through Georgia Tech while also participating in competitive kayaking required good balance and a bit of humor.

For example, during his last semester, Shipley's professor asked each member of the class to introduce themselves. The first student stated his name and said that he was a third-year senior, the next said she was a fifth-year senior, and so on. And, then it was Shipley's turn. "Hi, I'm Scott," Shipley said. "And I'm a 13-year senior."

Who could blame Shipley for his winding path to graduation when he was also competing for world championships and Olympic medals? When he did reach the finish line in 2001 with a bachelor's in mechanical engineering and in 2002 with his master's in ME, he held an impressive four world titles and had competed in three Olympics (1992, '96, and '00). His senior Tech project was designing a new kayak that he used to win one of those World Championships.

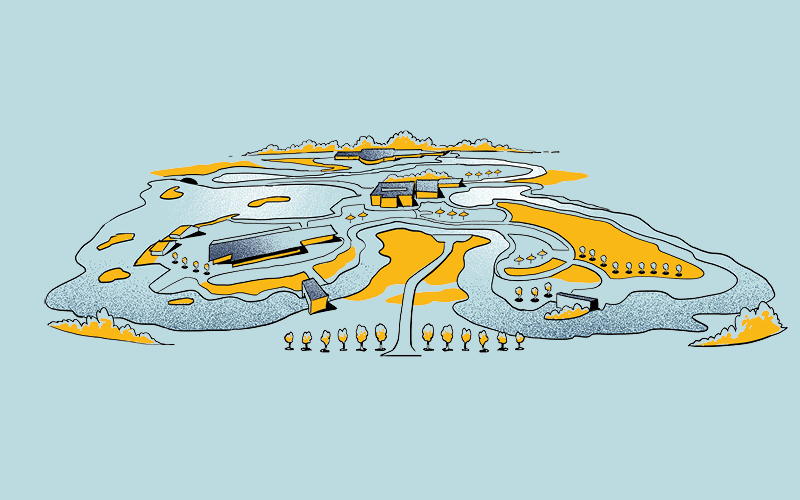

After graduation, Shipley leveraged his experience and degrees from Tech to design more than 20 premier whitewater centers around the world. One of his first projects was the U.S. National Whitewater Center, which features an enormous 3,750-foot man-made whitewater river. It was the largest man-made whitewater river in the world—until Shipley built the Montgomery Whitewater Center last year in Alabama.

The Montgomery facility boasts a 1,600-foot Olympic standard competition channel and a 2,200-foot creek channel that provides an approachable path for new and experienced paddlers.

"You can show up with your family and raft on the same channel that Olympians win gold medals on," Shipley says. "But we know that not everyone wants to get wet," he adds. The facility also includes plenty of spaces for dry activities like a conference center, ropes course, and mountain biking and jogging trails. "We set out to create this whitewater center, but what we've created in the end was an outdoor adventure center where everybody can find their adventure," he says.

Shipley's firm has revolutionized the design of whitewater courses. For the 2012 Olympic games, he was challenged to design a course that would be state-of-the-art 10 years into the future. The result was the invention of Rapid Blocs, a patented system of moveable blocks that allows for an infinite number of whitewater course design combinations. The polyethylene blocks can be moved to create new eddies or new waves.

Shipley says it wouldn't have been possible without Georgia Tech. "The life lessons I learned from Tech have made all this possible—the ability to run a design process and completely rethink the way we've done things—it makes me super thankful that I had that opportunity to go to Tech and was able to spend my 'short' 13 years there."

A World-Class Racetrack

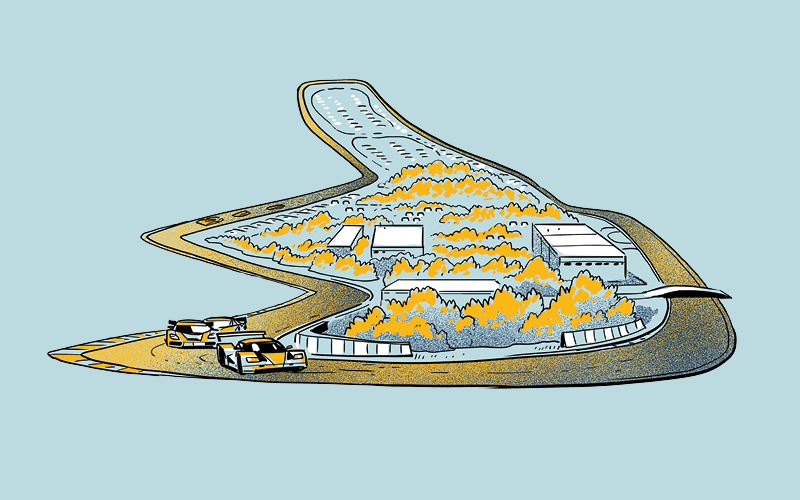

The 750-acre Michelin Raceway Road Atlanta, one of the world's premier road courses, got its start in 1969 with Ramblin' Wreck Earl Walker, AE 61, and his business partners David Sloyer and Arthur Montgomery.

After graduating from Georgia Tech, Walker became hooked on road racing. While working on Chrysler's Saturn Space Vehicle in Huntsville, Ala., he raced his family's Sunbeam Alpine, which he had modified with a roll bar, scatter shield, and a shoulder harness. "I was young and naïve and luckily never wrecked it," he shared.

By the time he moved back to Atlanta and met Sloyer, a southeast road racing champion, Walker was racing every chance he got. He and Sloyer read Dave Carnegie's classic, How To Win Friends and Influence People, and decided to apply the business guru's approach to their shared dream of building a world-class racetrack in Georgia. "We were young and indestructible and the positive attitude worked," Walker recalls. After their first attempt at buying and developing land failed, they found a piece of farmland in Hall County, Ga., and went to work transforming it into a racetrack. Their big break came in 1970 when a storm damaged a course in New York that was set to host the Can-Am series, which at the time was the most popular professional road race. The series needed a new track fast and moved the race to Road Atlanta, even as the course was still under construction. Walker and his partners accelerated their plans to finish the track and added new bathrooms, a concession stand, and other facilities for the event. With days left before the big race, they realized they needed a new building for ticket control. Walker found a company with a new quick-construction method, and they poured the foundation and framed the building with expanding foam over cloth. "It wasn't uniform and looked like a toadstool, which is what we called it. The woodpeckers loved it and it leaked when it rained but it served its purpose," Walker remembers. On the day of the race, he was outside the venue, directing traffic as tens of thousands of spectators rolled in. The race was an overwhelming success, but they didn't have time to celebrate because they were already preparing to host an even bigger race, the American Road Race of Champions, a couple months later. In 1978, Road Atlanta was sold to new owners, and it changed hands several times during the decades that followed. Today, Michelin Raceway Road Atlanta is owned by NASCAR Holdings and receives more than 400,000 annual visitors.

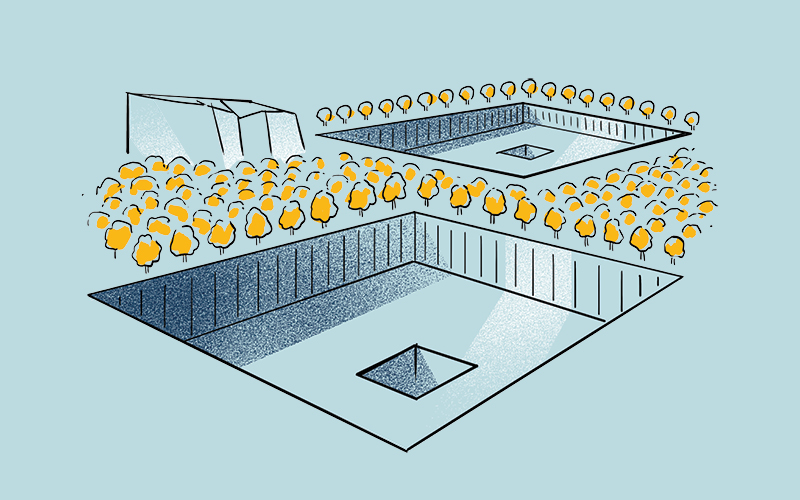

Reflecting Absence

The serene sounds of falling water bathe visitors as they gaze into two pools, each nearly an acre in size, that rest in the footprints of the North and South Towers of the World Trade Center. Along the edges of the pools are the names of the 2,983 people who lost their lives in the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. Architect Michael Arad, M Arch 99, designed the pools to represent "absence made visible." Water descends 30 feet into a square basin and then another 20 feet into a central void, making the pools the largest man-made waterfalls in North America.

Ponce City Market Revitalization

A swarm of Yellow Jackets played a role in transforming this historic building into a bustling hub for pedestrians and visitors. The revitalization of Ponce City Market in Atlanta's Old Fourth Ward involved restoring the Southeast's largest masonry structure, a 1926 building originally constructed by Sears, Roebuck & Co. Updating the building while preserving its history required the expertise of several contractors and nearly 3 million combined worker hours. Gay Construction Co., led by alumnus Tom Gay, IM 66, spearheaded the base building and site renovations. Several other Yellow Jackets at the construction company played crucial roles in the project, including Joe Thompson, CE 71, Mark Whitney, ME 03, David Martin, CE 93, MS BC 94, Rick Carswell, ID 94, and Tommy Herrington, IM 82.

The first phase of the 2.1 million-square-foot redevelopment opened in 2013 and has become a pedestrian-friendly economic hub in the Fourth Ward neighborhood.

The Big Chicken

Georgia Tech alumnus Hubert Puckett, Arch 57, designed the 56-foot-tall structure that over the last six decades has become a point of pride and a local landmark for the city of Marietta, Georgia. The Big Chicken was constructed in 1963 and restored in 1993 following storm damage. It underwent another renovation in 2017, when the rooster's moving eyes and beak were added. At 90, Puckett still designs buildings through his company U.S. Building Technology. He never expected the Big Chicken to become such a local phenomenon.

Tampa Bay Bucs' Pirate Ship

Chip Hayward, Arch 79, M Arch 81, was project manager and architect, representing the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, for the design and construction of Raymond James Stadium—an impressive 65,000-seat structure—but it's the 103-foot-long ship docked in the stands that was a dream come true for the architect and sailing enthusiast. "I got to fulfill my dream of designing a ship, even though it is still in and has never left dry dock," Hayward shared in 2009 with the Alumni Magazine.

Hayward says the biggest challenge was constructing the ship while the stadium construction was ongoing. The pirate ship was designed to be disassembled in quadrants so it could be removed to make room for the expanded temporary seating required for the Super Bowl; however the TV networks loved the ship and requested it remain for gameday broadcasts.

The stadium has been the location of three Super Bowls and, this past December, saw the Yellow Jackets beat the UCF Knights 30-17 in the Gasparilla Bowl.

"The Tampa Bay Yellow Jackets love when the Yellow Jackets come to Tampa," Hayward says. "We all feel more connected to Ma Tech when this happens, and we get to see our fellow alumni and families in a great venue. Go Jackets! THWg!"

GTRI's ARTS-VI

One of the largest systems ever built by the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is a new 142-ton threat simulator system that rolled out to the U.S. Air Force last June. The ARTS-V1 system, the first of three contracts with the Air Force, is designed to help pilots train for a variety of scenarios they might encounter in contested airspace and help them prepare for real combat situations. To put the size of the system in perspective, the radar unit is housed in a trailer that's 81 feet long and the operator unit requires a trailer that's more than 94 feet long. Transporting the system required the Air Force's largest aircraft, the C-5M Super Galaxy. More than 50 GTRI researchers and technicians contributed to the design of the system. Check out the list of alumni and students involved.

Georgia Tech alumni involved in GTRI's ARTS-V1

Dinal Andreasen, EE 77, Samuel Bass, MS ME 25, ME 23, Vince Camp, EE 83, Robert Case, MS ME 17, Henry Cotten, MS ME 74, ME 68, Dante Dimenichi, ME 14, MS ME 19, Robert Dunning, ME 23, MS ME 24, Zachary Eaton, ME 04, MS ME 06, Brian Faust, CmpE 04, MS ECE 06, MBA 18, Justin Fox, EE 03, MS ECE 06, Ian Harrison, ME 13, MS ME 20, Brian Holman, EE 06, Jacob Houck, ME 10, MS EE 12, MBA 17, Joshua Hurt, ME 19, MS ME 21, Burt Jennings, ME 81, Steven Johnston, ME 18, MS ME 19, PhD candidate ME 24, Joshua Judson, ME 22, Christopher Keel, MS ME 23, Daniel Kotten, ME 22, Ryan Lewis, MS ME 12 MS ME 24, Jeffrey McMichael, ME 18, Nicholas McGilvray, EE 18, Matt Rash, ME 11, CE 16, MS CE 19, Barry Sharp, EE 76, MS EE 81, Scott Travis, EE 08, M ASE 16, Max Tannenbaum, ME 14, MS ME 19, Michael Witten, MS EE 85

Current Students:

Kevin Kamperman II, MS ME 24, Austin Pettit, MS ECE 26, Daniel Polito, M ASE 24, Tyler Russell, MS ECE 24

Atlanta Beltline

From a master's thesis to a reality, the 22-mile Atlanta BeltLine was the brainchild of Georgia Tech grad Ryan Gravel, Arch 95, M Arch and M CRP 99. Gravel's idea to convert unused railroad corridors into a system of pedestrian-friendly trails connecting Atlanta has become an inspiration for sustainable growth and connectivity. By the end of 2024, 85% of the BeltLine's projects will be complete or actively under construction, with 10.4 miles of the main loop and 10.3 miles of connector trails finished.