Tech Engineers: Is This Word Missing From Your Degree?

By: Jennifer Herseim | Categories: Tech History

If you “got out” between 1945 and 1999 with an undergraduate degree in engineering, check your diploma. We’ll wait… Chances are high that you received a “Bachelor” rather than a “Bachelor of Science” degree.

In his first year at Tech, Van Leer dropped “science” from the name of Tech’s engineering degrees. This lasted until 1999, when the word was added back to diplomas. During that time, there were 45,806 “Bachelor of” degrees given at Georgia Tech. There have been only four since 1999 when the decision was reversed.

While nothing points to a difference in curriculum between the two degree types, if you’re a Tech engineer whose diploma reads “Bachelor of,” you might be wondering, why?

Engineer Turned Investigator

The questions started in the U.S. Air Force, says Al Clary.

“My local unit’s training office was confused about my record,” he remembers. “It said BAE, and they weren’t sure what it meant.”

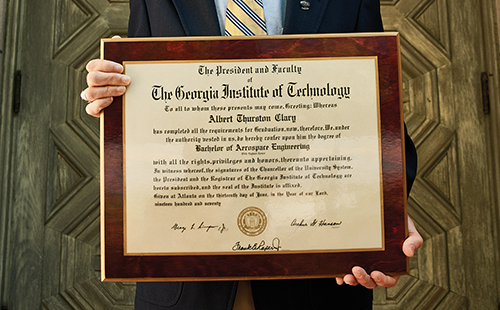

Clary received his Bachelor of Aerospace Engineering at Tech in 1970 with highest honors, was sworn into the Air Force Reserve, and got married to his wife, Judy (a graduate of nearby Grady Memorial Hospital School of Nursing), all within the same week. He stayed at Tech and obtained his Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering a year later and then entered active duty in the Air Force.

Is it a Business of Administration degree? A Bachelor of Arts degree?

When he left active duty in the Air Force, the confusion about his BAE degree followed. Clary retired after 24 years at Eastman Chemical Company and nine years at EBASCO Services, Inc. Along the way, he earned an MBA degree, became a licensed Professional Engineer, and worked with all types of engineers throughout the South. He also retired from the Air Force Reserve as a lieutenant colonel.

He never crossed paths with any engineer—aside from fellow Georgia Tech alumni—who did not have at least a Bachelor of Science degree. Even though the BAE degree never created any professional obstacles, the question still nagged at him from time to time. When his youngest son David graduated from Georgia Tech in 1997 with a Bachelor of Industrial Engineering, the mystery resurfaced.

“I never understood why it wasn’t a bachelor of science, and I dealt with engineers all over the South who all had their B.S. degrees,” Clary says.

In 2024, he searched for an answer.

Clary pored over course catalogs, contacted university archives, called the offices of the major national engineering professional organizations, and started to piece together why “science” was missing from his diploma—and 45,805 others.

Cracking the Case

Clary’s search zeroed in on a central figure—another proud engineer and veteran—Col. Blake Van Leer. Two other institutions where Van Leer had served as dean of Engineering also dropped “science” from some of their engineering degree names: North Carolina State and the University of Florida.

When Van Leer returned to Tech following World War II, his attention went to the Institute’s engineering programs. In his first year, he established the School of Industrial Engineering, now named the H. Milton Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering.

That same year, Van Leer made the case to the Board of Regents to drop “science” from Tech’s engineering degree names. In the 1944–1945 University System of Georgia annual report, Van Leer called it a “progressive step” that aligned Tech with standards recommended by the Society for the Promotion of Engineering Education (SPEE) and the Engineers’ Council for Professional Development. He added that “the word ‘science’ has been dropped from the designation of all accredited professional engineering curricula.”

Clary was able to locate an earlier report from SPEE in 1918 that recommended naming undergraduate degrees a “Bachelor of Science” in engineering, a recommendation that was reaffirmed by SPEE in 1930. It’s still not clear why or when the recommendation changed. “That part remains a mystery,” Clary says. “We don’t know for certain, but I imagine it had to do with elevating the engineering degree.”

Between 1926 and 1960, the number of schools offering “Bachelor of Engineering” degrees increased from eight to 33, SPEE records show. Georgia Tech was among those schools.

“There was clearly something influencing this shift,” Clary says. “By 1940, 45 states had taken over certification of engineers, likely driven in part because some engineering schools as early as 1900 had begun to issue professional degrees. These degrees that confer the title of engineer would simply say, ‘Civil Engineer’ or ‘Mechanical Engineer.’” While these degrees were different from Tech’s “Bachelor of” engineering degrees, the emphasis at the time was clearly to focus on the professional title, Clary says.

The other piece of the puzzle is why Tech didn’t add “science” back until 1999, Clary says. By comparison, NC State added the word back in 1959. Interestingly, a few universities still offer a “Bachelor of” degree in engineering disciplines, such as Vanderbilt University, but it’s rare compared to its peak in the 1960s.

One possible reason why Tech reversed the decision in 1999 is the switch from quarters to the semester system.

Early in his investigation, Clary reached out to Joseph Oefelein, professor and associate chair for Undergraduate Programs in the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering. Oefelein inquired with senior faculty, who pointed out that many of the degree programs received a slightly different name during the switch to the semester system, including the BAE becoming a BSAE.

Oefelein also confirmed that Tech’s BAE and BSAE are equivalent. “Aside from differences associated with advances in the state of the art over time, the required courses were essentially the same,” Oefelein replied.

War, Sputnik, & Engineering

“I realized this mystery is a story about the growing pains of the engineering profession in the first half of the 20th century,” Clary says. “Today, we think of engineering and Georgia Tech with so many students enrolled as being well established, but it hasn’t always been that way.”

One way to understand the “Bachelor of” trend is to look at the history of engineering education.

In the 1920s and ’30s, engineering struggled to gain a foothold. It lacked the prestige of more established professions of the time, like medicine and law. As World War II accelerated the need for progress in science and technology, engineers were often passed over for key wartime jobs in favor of scientists. Even well into the 1950s and ’60s, engineering educators debated how to draw more students into the profession and grow the reputation of an engineering degree.

In a talk delivered in 1982, L.E. Grinter, who had served previously as president of the American Society for Engineering Education, discussed how these trends didn’t shift until after Russia’s launch of Sputnik and the dawn of the space race. “It was a watershed moment,” Clary says. “It was a shock to the country that all of a sudden caused a need to push forward, to drive growth, and to drive the need for engineers,” he says.

In the end, Clary believes Van Leer and the other engineering educators who pushed for the “Bachelor of” degree name did so to elevate engineering at a time when it was less well regarded. And while Clary is searching for more answers, he’s coming to terms with how this story might end.

“I’m realizing we may never find out exactly what happened,” he says. Still, he’s satisfied knowing his BAE degree isn’t missing anything.