The Big Moment

By: Shelley Wunder-Smith | Categories: Tech History

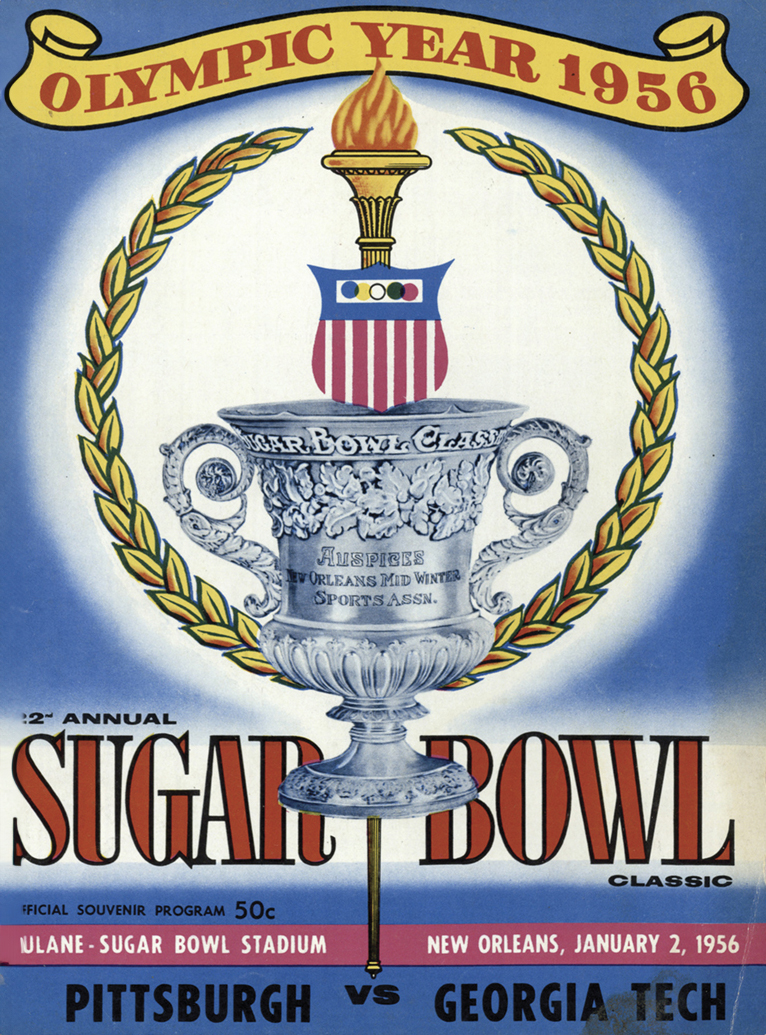

In 1961, Georgia Tech became the first university in the Deep South to integrate without a court order. Perhaps less well known is the Institute’s role in an earlier step toward racial integration: the 1956 Sugar Bowl.

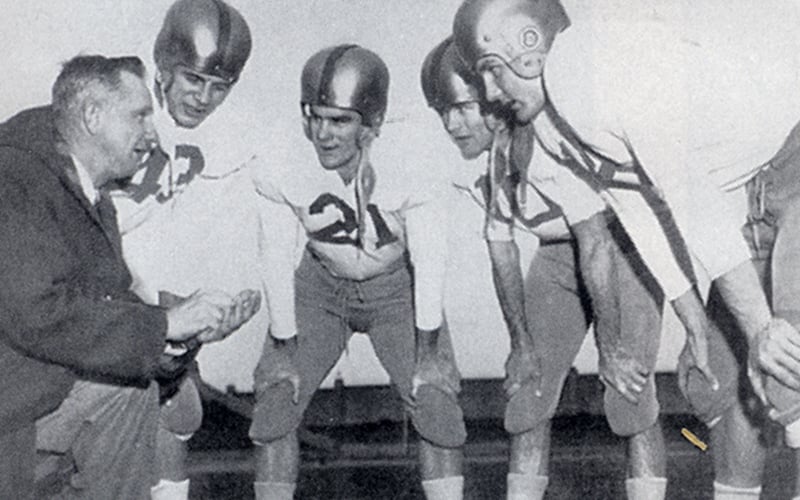

At the time, Tech belonged to the Southeastern Conference and commanded respect as a national football powerhouse. Under Coach Bobby Dodd, the team earned its third national championship in 1952 (shared with Michigan State) and enjoyed successive winning seasons, including multiple victories against the University of Georgia and in bowl games. So when the Yellow Jackets accepted an invitation to the Sugar Bowl, Tech supporters didn’t expect anything other than a possibly hard-fought win in New Orleans against the University of Pittsburgh Panthers.

This all changed when political officials in Georgia—staunch segregationists who had taken an openly defiant stance toward the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling—discovered that the Panthers fielded an integrated team. Pitt had one Black player, fullback Bobby Grier. And Grier’s appearance in New Orleans would make the Sugar Bowl the Deep South’s first racially integrated bowl game.

What followed was a storm that entangled politics and athletics and, for about a month, focused the eyes of the nation on Georgia. Governor Marvin Griffin demanded that the Yellow Jackets not go to the Sugar Bowl. At the prospect of their beloved Jackets being barred from play, Tech students rioted and burned the governor in effigy. After much contention, the University System of Georgia’s Board of Regents (BOR) voted overwhelmingly to allow the Institute to fulfill its signed contract with the Sugar Bowl. This was not exactly an achievement for integration, however. The BOR also mandated that no desegregated games, including teams and audiences, would be played within Georgia’s borders—a rule that was ultimately never enforced.

That said, the game itself represented a step toward racial equality. When Tech and Pitt met in Tulane Stadium on Jan. 2, 1956, no racial incidents occurred, and the overwhelmingly white, Southern crowd clapped for and cheered Grier’s performance.

According to Georgia Tech Professor Johnny Smith, who teaches a class on the history of American sports, “The color line was smudged here and there, erased and then redrawn. The history of civil rights and racial progress is complicated. Sometimes victories were followed by two steps backward.”

Events after the Sugar Bowl exemplified this. While the national Civil Rights Movement rapidly accelerated, Louisiana politicians, in an attempt to enforce segregation, passed Act 257, prohibiting integrated sports within the state. The Sugar Bowl did not host another Northern team for eight more years. On the other hand, just four years later, three young men set foot on campus as the Institute’s first Black students.

Breaking the Color Barrier in Sports

Below, read about the path to integration through these Georgia Tech-specific milestones (in blue), Black athletes in sports milestones (in gold), and civil rights milestones (in black).

1889

Three Black students—William Henry Lewis (Amherst), W.T.S. Jackson (Amherst), and Thomas James Fisher (Beloit)—break the color barrier for college football.

1892

Georgia Tech fields its inaugural, all-white football team.

1896

The U.S. Supreme Court upholds Plessy v. Ferguson, enshrining racial segregation as a means of keeping whites and non-whites “separate but equal.”

1899

Marshall Taylor, “the Black Cyclone,” wins the one-mile cycling sprint at the World Track Championships in Montreal—the first Black American to become a world champion in any sport, and only the second Black athlete in the world to do so.

1904

Georgia Tech hires John Heisman as college football’s first paid coach.

1917

Tech wins its first national college football championship.

1920

Fritz Pollard joins the Akron Pros as both coach and star player. He is the first Black coach in the National Football League. The next year he leads the Akron Pros to their first NFL championship.

1928

Tech defeats the University of California in the Rose Bowl (Jan. 1, 1929), the Jackets’ first-ever bowl appearance, and earns its second national championship.

1934

Georgia Tech refuses to play the University of Michigan until the Wolverines agree to keep Black star end Willis Ward on the sidelines. Under the “gentlemen’s agreement,” Georgia Tech benches star end Hoot Gibson in return.

The “Gentlemen’s Agreement”

As college sports grew in popularity in the late 1800s, segregated universities—most of them in the South—pushed to keep teams all-white. After 1910, many Northern universities began integrating their teams but informally agreed to keep their Black players out of games played in the South; in return, Southern schools would bench their players of similar skill and talent to ensure a fair contest. This was the so-called “gentlemen’s agreement.”

Eventually, Northern schools balked at leaving their Black players on the sidelines, and so some Southern schools quietly acquiesced to playing opponents with integrated teams—when the games took place above the Mason-Dixon line. Georgia Tech and UGA each played against integrated teams in the early 1950s.

1935

The Sugar Bowl is established. It is racially segregated.

1947

Jackie Robinson joins the Brooklyn Dodgers as Major League Baseball’s first Black player.

1948

President Harry Truman signs an executive order ending segregation in the U.S. military services.

In Dallas, Texas, the Cotton Bowl hosts its first integrated game.

At the London Olympics, American Alice Coachman becomes the first Black female athlete to win a gold medal—for the high jump.

1952

President Blake Van Leer opens the Institute to female students for the first time.

Michigan State and Georgia Tech, both undefeated, are designated national football co-champions.

1953

Georgia Tech plays an integrated Notre Dame football team at South Bend, Indiana. Notre Dame wins (27-14), breaking Tech’s 31-game winning streak.

The Sun Bowl, held in El Paso, Texas, holds its first integrated game.

1954

The Supreme Court rules segregated schools are unlawful in Brown v. Board of Education.

1955

August 28: Fourteen-year-old Emmett Till is lynched in Mississippi. His two murderers, white men, are later acquitted by an all-white, all-male jury.

November 22: Sugar Bowl officials formally invite the Pittsburgh Panthers, a racially integrated team, to play in the Sugar Bowl. Although Tulane Stadium is segregated, officials will permit the Pitt spectator section to be unsegregated.

November 26: At the annual Georgia Tech–UGA rivalry match, President Van Leer casually mentions to newly elected Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin that should Tech prevail, the Yellow Jackets will receive—and accept—an invitation to play in the Sugar Bowl. “Fine,” is the governor’s response. Tech wins, 21-3.

The Team Votes

Later, when the press eventually asked Tech’s star quarterback Wade Mitchell, Text 57, for his opinion about the furor, he said, “I personally have no objection to playing a team with a [Black] member on it, and, as far as I know, the rest of the boys felt the same way.”

That same weekend, Dodd polls his Yellow Jackets regarding the Sugar Bowl invitation, noting they will play against an integrated Pittsburgh team. The entire team votes to play.

November 29: Coach Dodd receives a telegram from former U.S. Ambassador Hugh Grant, one of the founders of the segregationist group the States’ Rights Council of Georgia, urging Dodd to uphold “our laws, customs, and traditions of segregation.”

Dodd gives the telegram to Van Leer and informs Griffin about it. A Griffin aide tells Dodd “not to worry about it.”

November 30: Robert Arnold, chairman of Georgia’s Board of Regents (BOR), which oversees Georgia’s higher-education institutions, notes that both Georgia Tech and UGA have previously played integrated teams (in the North). Arnold says he will not bring up the question of whether Tech should play in the Sugar Bowl because the BOR does not supervise the schools’ athletic events.

December 1: Rosa Parks refuses to give up her bus seat to a white man, which eventually leads to the months-long Montgomery Bus Boycott. The following November, the Supreme Court rules that segregated buses are unconstitutional.

December 2: Governor Griffin sends his now-infamous segregationist screed to the BOR. His telegram declares, “The South stands at Armageddon,” and demands that the regents prevent the Yellow Jackets from playing in the Sugar Bowl.

Governor Griffin’s Stance

“The South stands at Armageddon. The battle is joined. We cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in this dark and lamentable hour of struggle. There is no more difference in compromising integrity of race on the playing field than in doing so in the classrooms. One break in the dike and the relentless enemy will rush in and destroy us.” —Text of Griffin’s telegram to the Board of Regents dated Dec. 2, 1955

Meanwhile, the University of Pittsburgh announces that Grier will go to the Sugar Bowl and will “travel, eat, live, practice, and play” with the rest of the Panthers.

Late that evening, a crowd of around 2,500 students and supporters of Georgia Tech riot in protest of Griffin’s stance.

The Students Protest

Around 2,500 Tech students protested Griffin’s stance. They were not all rioting on behalf of racial justice. Rather, as Charles Griffin (no relation to the governor), a Tech freshman at the time of the riot, recently recalled, “We did not want to be denied the chance to play in the Sugar Bowl. Our team had a good record, and it just didn’t make sense. We decided we needed to do something about it, and we realized that if we only had a small crowd, the governor could chalk the protest up to the Northern students. So we went through all the dorms and got the students to all come out. We gathered at Peters Park and lit a bonfire.”

The crowd went to Little Five Points, where they hung an effigy of the governor from a light post. Charles Griffin explained, “My father worked for the railroad, and I had gotten a railroad flare from him and used it to light the dummy on fire. Then everyone marched up to the Capitol, where some of them tore up the bushes around the building and again burned the governor’s effigy.”

By 1:30 early the next morning, the crowd had gathered at the governor’s mansion, where Gov. Griffin was inside with the lights off. They were eventually convinced to disperse by a former Tech football player and state legislator, Milton M. Smith, who promised the protesters that Tech would go to New Orleans. The governor had been burned in effigy at least three times during the evening.

Tech’s quarterback, Wade Mitchell, would later tell his son, Wright, that his most vivid pre-game memory was “standing at his dorm room window, watching the students march up Techwood Drive toward the governor’s mansion” (at the time located in Ansley Park). Mitchell did not participate in the protest because Coach Dodd had told his players to “focus on football, not politics.”

Despite Dodd’s dictate, however, some football players joined the crowd of protesters. Carl Vereen, IM 57, a junior tackle on the 1956 team, recently said, “I participated, and there were quite a number of other players who did as well. We wanted to be allowed to play.”

On December 5, most unusually, a large crowd of UGA students gathered in support of the Tech protesters, carrying signs that read, “For Once, We’re for Tech.” Smaller groups of Emory and Mercer students also burned the governor in effigy on Tech’s behalf.

December 4: A front-page editorial in the Atlanta Journal calls the Sugar Bowl controversy “Griffin’s Teapot Tempest” and excoriates the governor for possibly damaging the state’s reputation among prospective business interests.

Georgia Tech’s student body president, George Harris, apologizes via telegram to the University of Pittsburgh for the governor’s actions, saying, “We look forward to seeing your entire team and student body in the Sugar Bowl.” Pitt’s student government responded with a telegram of their own: “The Pitt student body greatly appreciates the spirit shown by the Georgia Tech student body. We are looking forward to a great game on Jan. 2.”

The Game and After

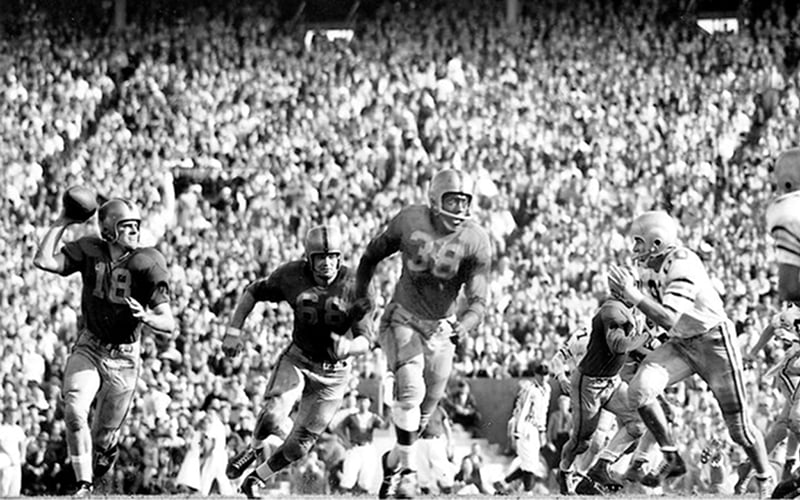

The Yellow Jackets–Panthers clash was a fierce defensive struggle. After a call against Grier with seconds left in the game, Georgia Tech won, 7-0. While the call was controversial, and the referee later admitted it was a mistake, no one thought it was racially motivated. Grier was the game’s leading rusher, with 51 yards.

The Yellow Jackets–Panthers clash was a fierce defensive struggle. After a call against Grier with seconds left in the game, Georgia Tech won, 7-0. While the call was controversial, and the referee later admitted it was a mistake, no one thought it was racially motivated. Grier was the game’s leading rusher, with 51 yards.

December 5: The BOR convenes a special session to decide whether Georgia Tech can play in the Sugar Bowl. After several hours of debate, Van Leer declares, “Either we’re going to the Sugar Bowl, or you can find yourself another damn president of Georgia Tech.”

The BOR settles the matter by voting to allow Tech to adhere to its previously signed contract with the Sugar Bowl. However, it also upholds the state’s segregationist policies, mandating that no integrated games (teams or audiences) will be played within Georgia’s borders.

1956

January 2: The No. 7–ranked Yellow Jackets play the No. 11–ranked Pittsburgh Panthers in New Orleans. Pitt fullback Bobby Grier takes the field, making this the first racially integrated bowl game in the Deep South.

January 24: President Van Leer dies of a heart attack, attributed to the stress of events surrounding the Sugar Bowl.March: 19 U.S. senators and 77 U.S. representatives sign the “Southern Manifesto,” pledging to oppose racial integration.

December 29: Georgia Tech and Pitt meet for a rematch, this time in the Gator Bowl. Tech prevails, 21-14. This is Wade Mitchell’s last turn at QB for the Yellow Jackets; Grier had already graduated and as such did not play.

1960

By a large majority, Georgia Tech students vote to give qualified applicants admission to the Institute, regardless of race.

1961

The Freedom Rides begin, a seven-month campaign to test the Supreme Court ruling (Boynton v. Virginia, 1960) in favor of desegregated interstate travel.

Three Black students—Ford C. Greene, Ralph A. Long, Jr., and Lawrence Williams—begin attending classes at Tech, making the Institute the first university in the Deep South to be integrated peacefully, without a court order.

1963

The March on Washington is attended by over 250,000 Americans of all races.

1964

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act into law, ending discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, and national origin.

Ronald Yancey earns an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering, becoming Tech’s first Black alumnus.

President Johnson also signs the Voting Rights Act into law.

1967

Harvey Webb, a first-year Black student, plays for Tech’s freshman men’s basketball team against UGA.

1969

Eddie McAshan, at quarterback, becomes the first Black player to receive a football scholarship and to start and play for Georgia Tech. Freshman weren't eligible to play for varsity teams, so he started in 1970.

1970

The first Black women—Adesola Kujoure Nurudeen, Tawana (Derricotte) Miller, Grace Hammonds, and Clemmie Whatley—enroll at Georgia Tech. Whatley and Hammonds complete master’s degrees in math to become Tech’s first Black alumnae.

Karl Barnes walks on to the football team, eventually becoming Tech’s first Black student-athlete and letterwinner to graduate. Barnes goes on to earn an undergraduate degree in industrial management (1973) and a master’s degree in architecture (1977).

1971

Karl Binns joins the Yellow Jackets men’s varsity basketball team as its first Black player.

1975

Jan Hilliard becomes Tech’s first Black female student-athlete to play for and letter in women’s basketball.

Arthur Ashe defeats defending champion Jimmy Connors, becoming the first Black men’s tennis player to win at Wimbledon.

1985

Outfielder K.G. White becomes Georgia Tech’s first Black baseball player.

1986

Debi Thomas wins the U.S. figure-skating singles championship, the first Black woman to do so, and also wins the world championship. Two years later, Thomas becomes the Winter Olympics’ first-ever Black female medalist, winning bronze at Calgary.

1990

Georgia Tech wins its fourth national football championship.

2022

Bobby Grier travels to Atlanta in honor of Juneteenth; at Bobby Dodd Stadium, he and Wade Mitchell shake hands for the first time since 1956.

Wade Mitchell and Bobby Grier Meet Again

In June of 2022, Bobby Grier—then 89 years old—made a trip to Atlanta in honor of Juneteenth. Together with his son Rob and President Van Leer’s grandson, Blake, they toured the National Civil and Human Rights Museum, the College Football Hall of Fame, and Georgia Tech. In a special surprise, Wade Mitchell met and shook hands with Grier for the first time since 1956. The group shared a meal at a local Atlanta restaurant, along with Mitchell’s son, Wright.

Blake Van Leer and Rob Grier are currently working together on a film called Bowl Game Armageddon. It will focus on Bobby Grier and Tech President Blake R. Van Leer, the 1956 Sugar Bowl, and the two men’s legacies. In a statement for a 2022 Atlanta Journal-Constitution article, Wade Mitchell said, “I greatly admired Bobby [Grier]’s courage during that time… There was a lot of pressure on Bobby, but he remained true to his values, and I hope that his legacy can be shared more widely through this project.”