The T-Files

By: Kelley Freund | Categories: Tech History

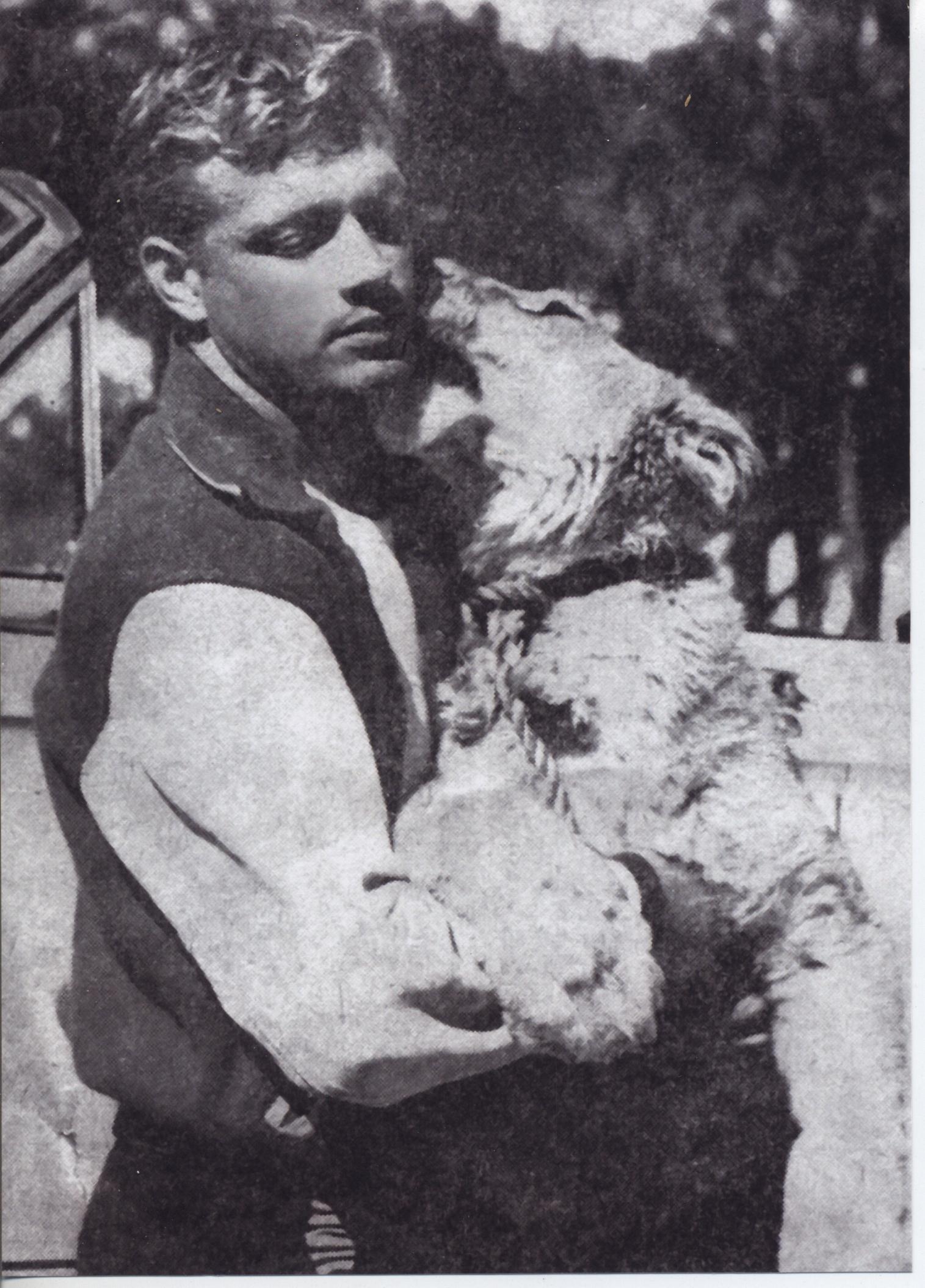

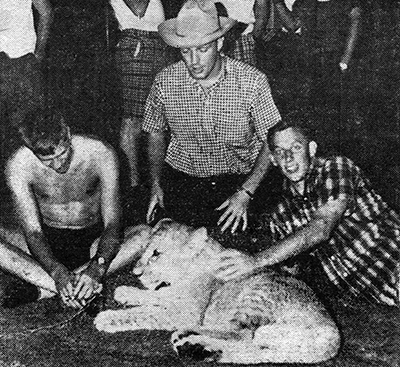

Joe Auer's Lion Cub

As the resident manager for a Georgia Tech dorm in the early 1960s, Bob Gahagan, IE 64, had to expect the usual student shenanigans. Still, he was quite surprised when he stepped out of his room one day to investigate some commotion: A lion cub was chasing three football players down the hall. The lion’s name was Clifford, and he belonged to footballer Joe Auer. Gahagan recalls a rumor that Auer bought Clifford from a fraternity at Emory. (But that was hearsay, and he was never sure if it was true.)

The lion’s name was Clifford, and he belonged to footballer Joe Auer. Gahagan recalls a rumor that Auer bought Clifford from a fraternity at Emory. (But that was hearsay, and he was never sure if it was true.)

“I remember seeing Joe Auer riding around with the lion in his car, the lion’s head and paws hanging out the back of it like a dog,” Gahagan says. “Everyone thought it was the funniest thing.”

The cub lived in Cloudman Hall, where residents would occasionally walk to the lavatories late at night, half-asleep, only to be startled fully awake by Clifford’s hot breath on the back of their legs. According to a 2014 issue of the Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine, the cheerleaders for the Northside High School Tigers painted stripes on Clifford and used him as a fill-in for their mascot.

The day Auer brought Clifford to Gahagan’s dorm, two other football players joined in on the fun. Clifford repeatedly chased Auer, Billy Lothridge, and Doug Cooper down the hall. But the boys rounded a corner that was too tight a turn for the lion cub, and he kept crashing into the wall.

“My thought was, ‘I’m enjoying watching this, but I’m going to lose my job,’” Gahagan says.

Another visit banished Clifford for good. During Gahagan’s time at Tech, a housekeeper came into the dorms to make up the beds and clean. Gahagan was in his room when he heard the maid screaming, “Mr. Bob! Mr. Bob!” He came out of his room to find the housekeeper rushing

toward him.

“There’s a lion in that room!” she yelled. It turns out the football players had put Clifford in Cooper’s bed for the housekeeper to find.

And that was the end of the lion in Gahagan’s dorm. He never saw the lion again. One source says that as Clifford got older, he began growling at night—a problem that eventually led students in the hall to sign a petition to send him away.

“If nothing else it provided me with great stories for years afterwards,” Gahagan says. “All three of the footballers have passed away, but they provided great entertainment both on and off the field.”

During the second quarter of the 1929 Rose Bowl game, a University of California player picked up a fumble made by Georgia Tech’s “Stumpy” Thomason, and then ran 65 yards in the wrong direction. The mistake led to Tech’s two-point safety on the ensuing punt, and Georgia Tech went on to win the game, 8-7. Somehow, the outcome of this victory was a bear named Bruin coming to Georgia Tech. While some sources claim Bruin was a gift from an adoring fan, others say the bear was given to Tech alumnus Chip Robert from the Rose Bowl committee, who then gave it

to Stumpy.

Either way, Bruin became known as Stumpy’s bear and was a familiar face around campus. A March 1929 issue of the Technique says Stumpy brought the bear to a fraternity house shortly after he got it to show off some of the stunts Bruin had learned. All was going well until Stumpy started a wrestling match. Bruin grabbed Stumpy with his claws, and Stumpy had to get three stitches in his hand.

Dean of Students Emeritus George Griffin once described the 400-pound Bruin “as smart as most Tech students with all the bad habits of modern youth.” The bear rode in the backseat of Stumpy’s car, and drank beer and Coca-Cola, often consuming as many as 20 Cokes at a time at the local drug store. Bruin was arrested for scaring residents, as well as for drunk and disorderly conduct.

Later in 1929, the bear went with Stumpy to Buffalo, N.Y., where Stumpy had earned a coaching position with a team called (fittingly) the Bears. It’s not known what happened to him after moving north.

In the days before Buzz, there was an unofficial mascot of the student body that attended classes from 1945 to 1947. Her name was Sideways, and she was a white terrier with a black patch over one eye who walked with her shoulders about 15 degrees out of line with her hindquarters. This interesting gait was due to injuries sustained when, as a puppy, she was tossed from the window of a moving vehicle in front of The Varsity. A local boarding house owner, Annie Schofield, nursed her back to health, and when Tech students saw the dog’s walk, they named her Sideways.

In the days before Buzz, there was an unofficial mascot of the student body that attended classes from 1945 to 1947. Her name was Sideways, and she was a white terrier with a black patch over one eye who walked with her shoulders about 15 degrees out of line with her hindquarters. This interesting gait was due to injuries sustained when, as a puppy, she was tossed from the window of a moving vehicle in front of The Varsity. A local boarding house owner, Annie Schofield, nursed her back to health, and when Tech students saw the dog’s walk, they named her Sideways.Sideways attended classes and athletic events, sampled food from the dining hall, and slept in different dorms each night. Once, a Tech man found her in the middle of the dance floor at the Delta Phi Epsilon’s fraternity house in Athens, apparently kidnapped by students from the University of Georgia.

In August 1947, Sideways accidentally ate some meat laced with rat poison outside one of the dorms. “She was buried by a group of students in the plot between the Textile Building and the Post Office,” according to the Technique.

The student council, along with a special committee, were able to secure a donated marble stone from the McNeel Marble Company of Marietta, Ga., which was then sent to Chicago, where an engraved likeness of Sideways could be placed on the monument. A dedication ceremony was held in March 1948 to honor what one Technique staffer called “one of the most beloved figures ever to set foot on the Georgia Tech campus.”Today, it’s said that placing a penny on her grave will bring good luck.

The student council, along with a special committee, were able to secure a donated marble stone from the McNeel Marble Company of Marietta, Ga., which was then sent to Chicago, where an engraved likeness of Sideways could be placed on the monument. A dedication ceremony was held in March 1948 to honor what one Technique staffer called “one of the most beloved figures ever to set foot on the Georgia Tech campus.”Today, it’s said that placing a penny on her grave will bring good luck.The Whistlenapping

It’s unclear when exactly the student body began to poach the Tech steam whistle. The Georgia Tech Living History Program notes the first “whistlenapping” occurred in either 1902 or 1903, “when two rival campus factions literally battled to determine which group would steal the whistle.” The lucky leader of the winning group was lowered out of a window to unscrew it. The whistle was returned anonymously the next day after a stern warning from the administration.

A 1964 issue of the Alumni Magazine does not mention this incident, instead claiming the first theft occurred in 1905, engineered by a student named L.A. Emerson. According to the Atlanta Constitution story following the whistlenapping, “The members of the faculty were almost frantic for a while, as they did not know how to summon the students. The wildest confusion prevailed.”

In this case, the culprits so feared the administration’s retaliation that the whistle was not returned until 1949. In a letter to the alumni secretary at that time, Emerson wrote, “The recollection of the student body being called into chapel and the fearful consequences promised the guilty parties still gives me a numb feeling all along my aging spine. It was even rumored that the cost would be taken from the ‘damage fees’ of the entire student body—unless the culprits confessed.”

According to the 1964 article, Emerson did end up confessing at some point to Dean George C. Griffin, who was involved with Georgia Tech in some capacity for almost 50 years. Griffin was presented with a stolen whistle as a retirement gift in 1964 from an anonymous group of students who called themselves the Magnificent Seven. The group had snatched the whistle on Oct. 31, 1963, before having it engraved, mounted on a base, and sent to Griffin via a delivery boy in May 1964.

Griffin turned the whistle back over to Tech, and the whistlenapping continued in the fall of 1981. Georgia Tech personnel housed near the whistle had complained so much about the noise that the hourly signal was discontinued, leaving the student body outraged. Students held the whistle for ransom, promising to return it only if it could continue its hourly blasts. A compromise was reached, allowing the whistle to return with the duration of its sound reduced from 10 seconds to five seconds.

When G. Wayne Clough was inaugurated as Georgia Tech’s 10th president in 1994, the whistle was supposed to be blown 10 times to signify Clough as the 10th president. However, Kevin Morgan, EE 95, and Duane Horton, BC 97, had stolen the whistle the night before, leaving the facilities staff to find a replacement, the sound of which Morgan later described as an “air burst…raspberry…blubbery sound.” The whistle was returned to Clough at a meeting in his office.

“I knew I was winding down on five years of hard mischief and thought this might be a good one to finish up on,” Smith says.

They built a ladder out of pilfered lumber, counting the bricks up the building to see how tall they needed to make it. Their original thought was to hang the clock in the middle of the night but realized that actually might draw more attention to roaming police. So around 8:00 on a November evening, Claxton held the bottom of the ladder while Smith attached the clock on the east side of Skiles. One person approached them to ask what they were doing, and when Claxton told him they were hanging a clock, the guy’s response was, “Far out, man.”

Smith and Claxton hoped the clock would be up long enough so they could take a picture; instead it was up for years. Eventually, the mechanism broke, and the plan was to just remove the clock. But there was such an outcry from the campus that a duplicate was built and placed back up.

Around the time of the clock caper, the Smaxton Organization concocted another scheme. This one represented some unfinished business on Smith’s part. Before he met Claxton, Smith and some other pals made an attempt to paint a giant GT on the back of Stone Mountain, getting two-thirds of the way done before they heard sirens and fled the scene. So a few years later, Claxton helped him finish the job. Within a week, staff at the park had painted over the GT, and while the gray paint made it more subtle, the Smaxton Organization’s handiwork was still visible, even 40 years later, when Smith found it on Google Earth.

In 2016 when Carl G. “Jere” Justus read the book Georgia Myths and Legends, one chapter especially piqued his interest. Chapter five was titled “Jimmy Carter and the UFO,” and it chronicled an interesting experience Carter had in 1969, when he was serving as a district governor of the Lion’s Club.

What did Carter see?

When Justus read Carter’s description in 2016, his thought was, “That sounds like an upper atmosphere barium release.”

He would know. In the 1960s, both as a graduate student and in his early days on the faculty at Georgia Tech, Justus was part of Air Force and NASA studies of the upper atmosphere in preparation for the Apollo missions. He spent his time at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, launching various chemical tracers into the upper atmosphere with small to medium rockets and observing the particle clouds. With barium, the clouds would initially glow bluish and then take on a reddish glow as some of the barium became ionized by sunlight. The rockets were launched at twilight, so the clouds would be sunlit at high altitude but it would be dark enough at ground level for researchers to observe the movement of the clouds against the dark sky.

Justus would go on to spend 18 years as a contractor at Marshall Space Flight Center and then worked as a consultant for Langley Research Center. He continues to read about science and study how the universe works. So when he read Carter’s report, curiosity got the better of him.

“It was the scientist in me,” he says. “I had to make sure what really happened.”

Justus dug up some records and discovered a rocket had in fact been launched from Eglin on January 6, around the time of Carter’s sighting. (Justus was back in Atlanta on January 6, so he was not involved with this particular launch.) The clouds would absolutely have been visible in Leary, about 150 miles away. They would have appeared 33 degrees above the horizon, and their increase in size and brightness followed by their subsequent decrease in size and brightness would have made it seem like the object was coming closer and then moving away, as Carter described.

Justus sent a letter to The Carter Center explaining his conclusions, which was then forwarded to the Carter family. In 2020, he completed an extensive study of these particular barium clouds and submitted the report to be archived at the Jimmy Carter Library.

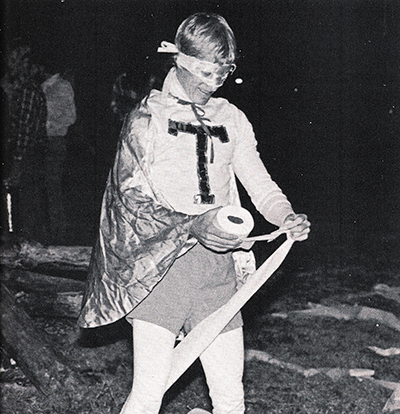

“Able to leap bar stools in a single bound. Faster than an elephant with the trots…” And the last line has been censored by the editor due to inappropriateness. But if you want to know the rest, you can talk to Rett Addy, EE 78. In 1974, he attended some of the weekly football pep rallies that featured the duo of T-Man and his sidekick, T-Squared, and remembers the duo’s intro, modeled after Superman’s.

Another alumnus, Greg Ross, IE 78, had a front-row seat to the spectacle a couple of times, when he was asked to fill in as T-Squared. It wasn’t a complicated gig—Ross’s instructions were to be goofy and run around.

“There wasn’t a heck of a lot to it,” Ross says. “It was all very simple. There was no inflatable 30-foot T-Squared somewhere. I had on tights, which I wasn’t used to wearing, a T-shirt with a ‘T’ on it, and a mask.”

T-Man and T-Squared were not as well-loved as Buzz turned out to be, and the duo only lasted a few years as Tech’s mascots. But for a little while, they delighted the hearts of Georgia Tech students.

“Tech is such a demanding, stressful place to be,” Addy says. “But these pep rallies were one of those things where you could go and just laugh for a bit.”

The superhero mascots impacted Addy so much that on gojackets.com, an unofficial Tech athletics website, his handle is T-Squared. Addy is also part of Tech’s Lunch Bunch, which gathers to hear coaches, ex-players, and administrators speak.

Ross also still bleeds gold. His house is painted yellow. There is a Georgia Tech corner in his home. And each year, he attends his fraternity’s reunion held at the property of a fellow brother. The group has been coming together for 40 years, and they now have three generations of Tech alumni in attendance.

“Attending Georgia Tech was one of the top two or three things I’m happiest about and proudest of in my entire life,” says Ross. “So to say that I was something at Georgia Tech, to say I was T-Squared a couple of times, that’s a thrill for me.”

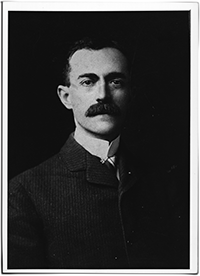

President Lyman Hall's Ghost

While serving as Georgia Tech’s second president from 1896 to 1905, Lyman Hall added four new degrees to the academic roster: electrical engineering, chemical engineering, textile engineering, and general engineering. But perhaps what he was most known for was being a disciplinarian. It’s said that the West Point graduate was known as Captain Hall instead of President Hall. In 1901, he suspended the entire senior class of 18 students for returning to classes a day late after the Christmas holidays, forcing them to return during the following fall semester.

While serving as Georgia Tech’s second president from 1896 to 1905, Lyman Hall added four new degrees to the academic roster: electrical engineering, chemical engineering, textile engineering, and general engineering. But perhaps what he was most known for was being a disciplinarian. It’s said that the West Point graduate was known as Captain Hall instead of President Hall. In 1901, he suspended the entire senior class of 18 students for returning to classes a day late after the Christmas holidays, forcing them to return during the following fall semester.Hall became ill during his time at Georgia Tech and passed away in 1905. Although he didn’t die at Georgia Tech, some students have claimed run-ins with his ghost in and around his namesake building. Ever the disciplinarian, Hall is perhaps maintaining a presence to ensure students are behaving and studying.

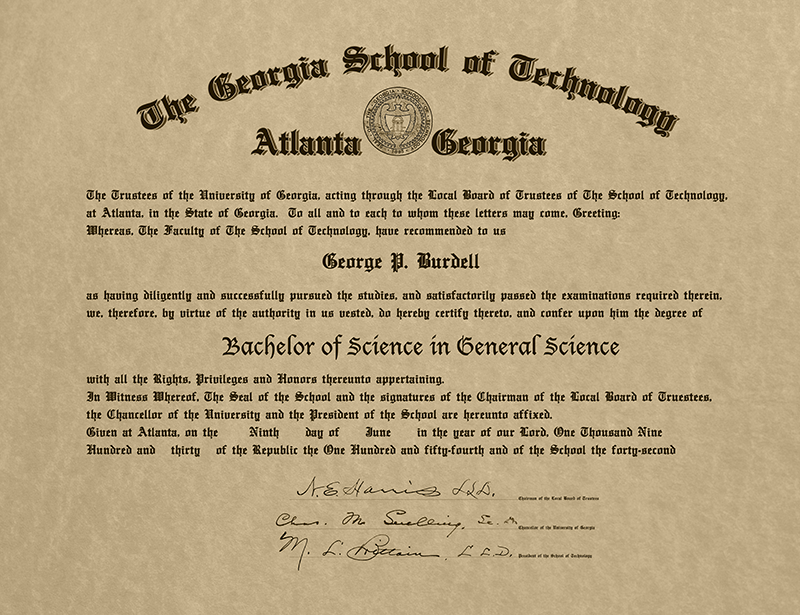

George P. Burdell

In 1927, when William Edgar “Ed” Smith accidentally received two enrollment forms for his admission into Georgia Tech, he got an idea. At the time, Smith was a student at the Richmond Academy in Augusta, Ga.; the president of the academy was George P. Butler, a former University of Georgia football captain. Smith decided to enroll the president to Georgia Tech, but lost his nerve and instead used the maiden name of his best friend’s mother, Burdell.

But he didn’t stop there. Smith developed Burdell into an actual student, enrolling him in classes and turning in extra copies of homework assignments and exams, changing his handwriting style so professors would be none the wiser.

Burdell went on to receive a bachelor’s degree and master’s degree in mechanical engineering from Tech. And still, the joke wasn’t over. He was listed on the flight crew of a B-17 bomber, flying 12 missions in Europe with the Eighth Air Force in England during World War II. In 1958, members of the senior class of Agnes Scott College announced the wedding engagement of Burdell and fictional Agnes Scott student Ramona Cartwright in the Atlanta Journal.

In 1969, Georgia Tech computerized registration, but somehow Burdell managed to enroll in every course the Institute offered—over 3,000 credit hours. This happened again in 1975 and 1980.

Over the years, Burdell has fought in other wars, served on the board of directors of MAD magazine, and led in online polls for Time magazine’s Person of the Year. He has a Facebook and LinkedIn page, and apparently joined the faculty of Georgia Tech in 2005.