Freddy Lanoue, a revered swim coach at Georgia Tech and an accomplished swimmer and diver in his own right, didn’t believe in doing anything halfway. As the world edged ever closer to war in the late 1930s, officials in the Navy tapped him for a big job: come up with a water survival technique that sailors could use to stay alive in worst-case scenarios. He did. His “drownproofing” method — a process that allowed people to stay alive in the water for hours while conserving energy—was adopted by the Navy and continues to be taught to Navy SEALS today. Among Lanoue’s first guinea pigs as he honed his method were Georgia Tech athletes and students, who ultimately learned to perform the technique with both their arms and legs tied. The skill was considered so essential that it was a graduation requirement—at least some version of it—for students until 1986. Most alumni consider learning it a badge of honor.

While students today might not be familiar with drownproofing, there’s no question it's had a lasting impact, says Tech’s Living History Program Director Marilyn Somers. “I go out and tell stories and mention drownproofing. People almost always come up to tell me their story about how they used it to save their life,” she says. “It really does work.”

The sun was just beginning to set when the propeller snagged the towrope and the mosquitoes swarmed the idle runabout. Back at the houseboat, still tethered to the dock, the celebration was in full swing: cold drinks and fresh barbecue and so many toasts to the bride-to-be. Little did they know the groom had literally jumped ship; that he and his best friend, unwilling to endure another blood-sucking bite, had chosen to swim several hundred yards back to the party rather than wait for help; that they’d spent all afternoon swaddled in the Arkansas heat, skiing and boating and hamming it up, and were now foolishly racing to shore from the middle of the lake, several drinks deep.

“I just dove in with him,” says Ed Beard, IM 57. But of course, his friend was a competitive swimmer, and Beard was not, and roughly halfway back, “I just gave out.” His 23-year-old ego couldn’t propel him any further. His adrenaline was drained. He was cramping and beginning to panic.

“Johnny,” he sputtered. “I’m in trouble.”

His friend, a fellow Phi Delta Theta, circled back. He reminded Beard of their “drownproofing” course at Tech, and though Beard hadn’t passed every test, the term itself triggered his better instincts. He remembered all the hours he’d spent in that old campus pool, the rigorous training he and his peers had endured: the underwater obstacles, the pint-sized swim coach barking orders. He slowed his breathing, “got my mind settled down,” he says, and began to alternate between a back float and—when his strength returned—a slow front crawl, off and on, back and forth, swallowing one creeping doubt after the next, relaxing again whenever the cramps returned, until finally the houseboat was in reach.

“They were all partying and carrying on,” he says. “I don’t think I even said anything about it—but I never forgot it. I knew I was in trouble.”

Nearly 60 years later, after a career in investment banking, Beard noticed a discussion on the GT Swarm chat forum about drownproofing, a term he hadn’t heard in years. He posted a short note about his own harrowing experience on that lake near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, so long ago, and how “the GT drownproofing course…saved my life.”

“I did that mainly to give credit to [coach] Freddie Lanoue,” he says. " I may be here posting because of that course."

Born in Brockton, Massachusetts, in 1908, Frederic Richard Lanoue, a self-described “Spartan disciplinarian,” sparked a revolution in water safety. “Although his voice suggested a permanent cramp in mid-stream and his physique was more suitable for right guard than Australian crawl,” reported the Knoxville News Sentinel following one of his numerous speaking engagements in January 1954, “Fred was a surprising hit with the audience…And he was interesting, too.” He wore exclusively second-hand clothes and a gap-toothed smile, and though he barked orders like a drill sergeant, his hairline receding a little further each year, his students adored him.

“He was emphatic about every statement he made,” says Ed McBrayer, AE 68. “He was quick to tell you if you were doing something wrong, and rewarded you if you did something right.”

Though once a competitive swimmer, Lanoue himself was a natural “sinker,” he said, all muscle and bone. He couldn’t float—not without a great deal of effort, anyhow. And thus in 1938, as a young swimming instructor at the Atlanta Athletic Club, he began developing a system he called “drownproofing,” or “a new survival technique that can keep you afloat indefinitely,” he wrote in his popular 1963 book for Prentice Hall, the educational publisher—even his fellow sinkers. In its most basic sense, drownproofing is a method of controlled breathing that allows one to conserve energy while suspended in water, no matter the circumstance: wet clothes, body cramps, rough seas, and more. But while Lanoue’s instruction was often physically punishing, a fortified mental fitness was the ultimate goal.

“This technique is better and cheaper than any insurance or life-saving gadget a man can buy,” Lanoue once said. “What we’re trying to accomplish is a change from fear of water to respect for the water.”

When Tech opened its new swimming pool at the Heisman Gym in 1939, the college hired him as the head swim coach. With Lanoue at the helm, Tech would win four SEC championships within the next decade and change, and in 1958, he would be elected president of the College Swimming Coaches’ Association. But just one year after he arrived at Tech, he also began teaching a quarterly drownproofing course—what he would ultimately consider his crowning achievement—to everyone who enrolled at Tech. The course proved so popular, so obviously practical, that it remained in the school’s course catalog until 1986, decades after Lanoue had died and his successor, Coach Herb McAuley, EE 47, took the reins.

“It was intense, but I don’t remember anybody throwing shade at the course,” McBrayer says. “Everybody thought it was a great thing to learn, and they were very proud that they had been through it.”

Tech students often spoke of drownproofing like a rite of passage, like boot camp—and for good reason. Lanoue’s primary objective was to keep his students above water in the event of an emergency, but he didn’t stop with a simple bob alone. Each course grew increasingly more difficult. Students eventually found themselves lashed to a 10-pound weight, sinking to the bottom of the deep end with their hands and feet tied together, tasked with staying afloat for a minimum of one hour. In perhaps the most extreme exercise, students were instructed to jump feet first off the diving board, push off the bottom, and swim the entire length of the 25-yard pool. And then back again. Underwater. Lanoue developed the test to simulate a particularly extreme boating accident in which one might need to swim out from beneath a flaming oil slick.

McBrayer still remembers the euphoria that washed through him just before he passed out—so eerily similar to the way Lanoue had once described it. He made it all the way down, and halfway back, the pressure mounting with every kick, every stroke, his blurry peers hovering poolside, and when his heart finally threatened to punch straight through, he felt a sudden, uncanny relief.

McBrayer still remembers the euphoria that washed through him just before he passed out—so eerily similar to the way Lanoue had once described it. He made it all the way down, and halfway back, the pressure mounting with every kick, every stroke, his blurry peers hovering poolside, and when his heart finally threatened to punch straight through, he felt a sudden, uncanny relief.“I started feeling like I don’t really care if I go up or not,” he says. “And the next thing I knew I was gagging and coughing on the side of the pool, and two guys had me by the arm.”

But Lanoue didn’t save his drownproofing course for Tech students alone. He also taught Naval Cadets and Peace Corps volunteers as a “water safety consultant,” and was hired to conduct private and public drownproofing seminars across the country. According to the UPI, both the British Royal Family and President Kennedy took great interest in his work, and the diminutive coach became so locally adored that Celestine Sibley, the celebrated Atlanta Constitution columnist, called it the “Fred Lanoue cult.”

“In Atlanta, there is a sizable community of citizens who think that the Georgia Tech swimming coach, Fred R. Lanoue, is the greatest man in the world,” she wrote in a June 1963 review of his book, Drownproofing: A New Technique for Water Safety. “They speak of his genius, his tough- fibered intelligence, his patience, his imagination.”

Sibley then praised the book herself, calling it “a fascinating revelation of how much research and study is going on locally in water safety.” Drownproofing reached thousands beyond the Heisman Gym, as did the serialized version later published in The Atlanta Constitution. But it was never quite enough—not for Lanoue. He often reminded his audience that roughly 7,000 Americans drown ever year, and claimed that at least 6,500 could survive by practicing his drownproofing technique. And so the “Spartan disciplinarian” kept at it, spreading the gospel of water safety wherever and whenever he could: to Mobil Oil Company employees in Lafayette, to children with physical disabilities at Georgia’s Warm Springs Foundation, and on the very day he died, to the Marines stationed at Parris Island in South Carolina.

“Never mind pretty little swimming pool situations. What is the worst situation you might run into from a swimming standpoint?” Lanoue once told a reporter at the Lexington Herald-Leader. “…Any ‘drownproofed’ person can handle this situation with ease. Can you?”

Drown Proofing Remembered

Howard Tillison, EES 74

On March 1, 1978, I was pilot in command of a Navy HH-46A helicopter that experienced a mechanical failure, causing us to hit the water going backwards, vertically, and at about 100 mph. Much to my surprise, I was still alive and conscious after we crashed, and I found myself immediately submerged with bubbles rising around my face at the moment of impact. As I went through my training steps to escape from the sinking helicopter, my escape door was jammed, so I had to try a couple of different approaches before I was finally able to plant my feet and push hard enough to get the door open. At that point, I was somewhere between 30-60 feet deep (it's a long story how I know that, but I know that), and I was able to partially inflate my CO₂-powered flotation device.

When I saw the partially inflated "lobe," I knew that it would take me to the surface if I could hold my breath long enough. I had taken my last breath somewhere around 100 feet above the surface and had held it by the grace of God and the DISCIPLINE I learned in the GT Drownproofing class. I was able to relax and continue holding my breath, knowing that I was rising to the surface, even though I was exhausted from the effort of breaking out of the wreck. It was later estimated, based upon eyewitness accounts of the crash as seen from the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, that I was underwater for about two minutes, holding that single breath I took before impact. I directly attribute my survival to my GT swimming class and the skills I learned there.

Phillip Gossage, Cls 69

My roommate and I took Freddie's Drownproofing class in the fall of 1964. Being swimmers all our lives, plus having earned our senior Red Cross Lifesaving certificates, we were like ducks in the water. We enjoyed and embraced learning the "new" technique. However, of our class of about 40 students, half came from rural parts of Georgia and had not been in water deeper than 6-inch creeks their entire life. Freddie showed no mercy to those who stood on the side of the pool. He gave them ten seconds to make up their minds, yelling, "Get your [a**] in that pool, […] or I will throw you in!" If they hesitated, he would physically throw them into the deep end. While we laughed, we also felt sorry for them, seeing the terror in their faces. The course had nothing to do with learning to swim. It taught facing fear down and developing self confidence in tackling and later mastering something that one feared. This lesson stuck with most of us students for the rest of our lives.

The Underwater Brick

Mary Lou Wotring, TE 81

The underwater swim was the very last thing I had to do to graduate... I kept popping up for air about fifteen feet from the end of the pool. Coach finally threw a brick in the water where I kept stopping and said, "When you see the brick, you just have to go fifteen more feet to get your diploma."

It worked!!! Everyone there was cheering for me as I passed the brick. Coach took pity on me and gave me a "C" as a graduation present.

Success, Failure, and Brief Unconsciousness

William "Bill" Moore Jr., EE 64

Along with 25 other innocents, I filed into the bleachers beside Georgia Tech’s indoor pool and took a seat. Coach Fred Lanoue climbed out of the water and toweled himself off. Grabbing his clipboard, he called the roll. He was the head coach of Tech’s swimming team and the notorious creator and instructor of PT 101 - Swimming. I sized him up. He couldn’t have been more than 5'2", and he looked old enough to be my grandfather. He had on only the briefest of swimsuits, one I would have been embarrassed to wear. He was bald, skinny and shrunken. A misshapen leg hung from his left hip. He didn’t so much walk, as he sidled. Though his bearing was not impressive, his voice was. He spoke with a kind of gruff bark, with great authority, as if he were a drill sergeant lecturing a bunch of new recruits.

“This is a swimming class,” he growled, “but I’m not here to teach you how to swim. You should know that already. If you don’t, it’s too late for me to do much about it.” A not-so-great swimmer myself, I wondered what any non-swimmer must be thinking. He went on. “What I am here to do is teach you how not to drown. Listen carefully, do exactly what I tell you, and you’ll never, ever be in danger of dying in deep water.”

Coach Lanoue’s method for not drowning was called Drownproofing. We spent weeks learning it. In theory, it was simple. You took a deep breath and assumed the position of the dead man’s float: your head, arms, and legs hung down in the water. Every twenty seconds or so, you brought your head up and refilled your lungs, expending as little energy as possible while treading with your arms and legs. You then resumed the dead-man position. It was Coach Lanoue’s contention that by establishing a steady rhythm of these moves, anyone could stay afloat for hours. Much as I tried, I couldn’t master the steady pace that Drownproofing required. Some days, I might be able to sustain it for fifteen minutes. Others, I’d have to swim to the side of the pool after only five. Coach Lanoue had little patience with slow learners. His idea of poolside assistance was a push on your head — with his bad leg.

As we approached the time for the first test of our Drownproofing prowess, Coach Lanoue described what we‘d be doing. “Take this piece of rope. Cross your ankles and tie them together with one end. Loop the other end around your waist and tie it back to itself at your navel. Crawl to the edge of the pool and push yourself in. Use Drownproofing to stay afloat for twenty minutes. I’ll time you. After that, use Drownproofing and your arms to swim your way across the width of the pool — two times. Go to the bottom. Retrieve this plastic ring you’ll find there. Do all that, and I’ll give you an A. Anything less, and I’ll decide how much credit I think you deserve.” Was he serious? Damn right he was!

Test day came, and the best I could manage was the twenty minute float and one side-to-side swim. I was surprised that I had managed even that. Amazingly, half the class did it all. The tests that followed weren’t any easier. We had to perform similar feats with our hands tied behind our backs, then with both our hands and feet tied. I muddled through with minimal credit. Was I going to pass this course? I'd certainly hoped so. It was required in order to graduate. There was a senior in our class who had failed two previous attempts. I was relieved that we were finished with basic Drownproofing.

The test that followed was more to my liking. Jump from the high platform with your clothes on. Take off your pants, knot the legs, and inflate them into a makeshift life preserver. Use it to stay afloat for fifteen minutes. I’d done this in Boy Scouts. I did it again for the test. Things were looking up. Coach Lanoue described our final challenge: a 50-yard swim, two lengths of the pool, down and back, from a diving start. There would be two wrinkles. The first: we’d have to stay underwater for the entire swim. The second: just to be sure that the diving start didn’t give anyone an advantage, we’d have to do an underwater flip immediately after we’d dived. Coach said the whole test should take each of us about a minute. Even some of the good swimmers in the class seemed concerned. Fifty yards underwater was a long way. One minute without a breath could seem an eternity. Coach Lanoue was sure that everyone could do it. And again, he had a method. If we just did what he was going to teach us, there was no way we could fail. “Just like drownproofing,” I was thinking.

Part one of Coach Lanoue’s method: “Before you dive, hyperventilate. For about a minute, take deep breaths in rapid succession. Make each exhale as long and forceful as you can. Inhale naturally after each exhale. When your fingers begin to tingle, you’re ready to dive." Part two: “Take long, smooth, steady strokes with your arms, and make frog-like kicks with your legs. Glide. Relax. There’s no rush. There’s plenty of oxygen in your lungs. When you reach the far end of the pool, turn and push off with a good kick. Glide and stroke some more. You’ll be back to where you started before you know it.” I practiced this swim diligently for two weeks. I practiced it during classes, and I practiced it between classes. I must have gone through twenty rehearsals. Breathing, diving, flipping, stroking, kicking, turning, gliding — I polished all my moves. But during none of this practice was I ever able to make it further than about thirty of the required fifty yards. An undeniable need for air would take hold, and I’d have to surface. Test day arrived.

We sat in the bleachers waiting for our turn to be called. Coach Lanoue prefaced the session with new information. It was possible, he said, that some of us might pass out during this test. Not to worry. The body’s natural reaction, when this took place, would be to prevent water from coming into the lungs. If he saw it happen to anyone, he’d have them brought out of the water, and they’d get an automatic A. I wanted no part of that outcome. As the first swimmer took his dive and made his flip, Coach Lanoue droned. “Those of you who think this guy might need help are welcome to begin the first verse of ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers.’” A few who apparently appreciated the irony started singing. But most of us just stared with growing wonder. The brave soul we were watching made a clean turn, stroked smoothly through his final lap, and emerged, arms raised, at the finish. Cheers rang out across the pool and echoed off the walls. It was indeed possible to complete this test. Even more incredibly, the next five swimmers succeeded. Coach Lanoue shouted their times as they touched the finish. Each one was within ten seconds of the sixty he had told us we would need. The class was on a roll. I was becoming a believer. But would I be the one to break our streak?

A classmate we all knew to be a poor swimmer nervously took his place at poolside. He hyperventilated and dove. His flip left him pointed in the wrong direction. A few tentative strokes took him into the side wall. He bounced off and headed back to where he’d started. Another ten seconds of going nowhere, and he’d had enough. He surfaced, dog-paddled to a ladder, and climbed out. Coach Lanoue muttered an unintelligible curse. “Thank God”, I thought. “I won’t be the first."

Then Coach Lanoue’s prediction came true. An accomplished swimmer, he stretched his arms forward, five yards from the finish. His body froze. The coach watched intently (as did we all) for about five seconds. Coach signaled an assistant who was standing poolside to go down and bring the student up. In his rescuer’s clutches and gasping for air, he looked blankly in our direction, as if he just awoke from a crazy dream. Later, he told us that he didn’t remember anything beyond his dive. Coach had called it. The student had no water in his lungs. And he’d earned his "A."

By the time my turn came, I had seen it all: success, failure, and even brief unconsciousness. I stood at the end of the pool. Exhaling and inhaling, with extreme emphasis, as Coach Lanoue had stressed, on the exhales. I felt he ends of my fingers tingle. It was time. I dove. I vaguely remember turning my flip and taking a couple of strokes. My next recollection is of touching a wall and kicking back toward where I’d come from. I saw the break in the pool bottom where shallow water began tapering down to deep. The last five yards didn’t register. I touched the finishing wall and heard the coach’s voice, “Sixty-three seconds!” Then, the clapping of hands. I'd never known a prouder moment. I’d aced the test and passed the course. And I’d done it with a feat that sounded impossible when I’d heard Coach Lanoue describe it, a feat I’d not been able to do in practice, a feat I’d surely never have to do again.

Coach Fred Lanoue died unexpectedly in 1965. He was teaching drownproofing to Marines at Parris Island, S.C., when he suffered a heart attack. His legacy has lived on in stories that his students still tell and in a book he wrote about drownproofing. Drownproofing continues to be used for training in the military, the State Department, and the Peace Corps. As ornery and didactic as he seemed, I’ll never forget Coach Lanoue’s incredible course nor the knowledge and courage he gave to me and others in order to complete miraculous accomplishments.

Wrong Way!

Quenton "Lanny" Gilbert, ICS 84

The course final was to jump off the high dive, turn a complete somersault underwater, and then swim the length of the pool underwater. The lady ahead of me was doing well, until she got about halfway to the end, at which point she started swimming toward the left side of the pool. When she reached the side, she pulled out of the water with a triumphant “Yes!” complete with a fist pump. When she realized she’d swam to the side of the pool instead of the end, she said “Dang it!" and had to do it over again.

Reginald Robinson, CE 57

As a third-quarter freshman, I took the “swimming” class during the summer of 1953 under Coach Freddie Lanoue. I hated every minute of it! Because I did not like to be tied up and perform the required skills for grades, he had the gall to flunk me! I remember one of his favorite expressions was “Blow, sucker, blow!”

That quarter was a disaster for me at Tech. I roomed in Glenn with three other guys, which was a big mistake! Studying was a problem because someone was always creating a disturbance. I also flunked first-quarter calculus, which caused me to be placed on probation for the next quarter. Fortunately, I passed all classes the next quarter and every other quarter until graduation in 1957. I delayed repeating the water survival class until the summer of 1954. The administration kept reminding me that “I’d better take it again if I wanted to graduate.” I passed the class under Coach Herb McAuley with a “C” grade. What a relief that was.

Elizabeth "Beth" Logan, EE 86, MS EE 86

First, I am so sorry to hear that GT doesn’t even offer the class, not even as an elective. The lore of the class was all about the horrors, and I am more of a hiking/biking kind of gal than a swimmer, so I delayed taking it. Finally, I did. There were about 20 men in the class and 4 women. One woman went to the “fear of water” class, one dropped out, and one broke her wrist. That left me, 5’4” and 118 pounds, with 20 guys. Thankfully, my wonderful professor got a woman from the swim team to be his assistant. She became my partner when needed. The tallest guy in the class complained that I should be his partner because we needed to know that I could rescue a bigger person. The professor promised that during an emergency my adrenaline would kick in and I would rescue him.

We began taking the test each week, and I passed the first nine at 10 points each; that was a 90! I was really looking forward to having a perfect score in at least one class at GT, but it wasn’t to be. The professor said, “Don’t come back to class.” I started to argue when he said, “You have your 'A,' and I have a lot of students to get through this class.” While I may have never taken the last test, I still am proud to have learned everything. Just last month, I offered to teach all my neighbors' children in one of the neighbor's pool. I wish more people learned it.

Troy "Gene" Barber, IE 62

Successfully passed the individual test requirements of staying afloat — feet tied, hands tied, removing clothing, and floating — but had to have monitor assistance remove me from the pool on the test to stay afloat with hands and feet both tied behind, suspended midway between top and bottom of pool. Being removed twice on the test day, I received a "C" passing grade for this test and a successful passing grade for the course.

Charles Clark, IE 72

In 1967, you were required to take one quarter of swimming, track, and gymnastics as part of your first-year curriculum. I chose swimming for my first quarter, because I had been a very active swimmer prior to attending Tech. I believe our instructor was Coach Nelson at that time. Anyways, I was able to complete all of the required tasks for the Drownproofing course during the first half of the term, and I spent the second half helping others. The most challenging activity for me was the requirement to swim down and back underwater on a single breath. Coach Nelson explained to me how the secret was to hyperventilate first to get the highest amount of oxygen in your lungs, and then to take your time underwater with slow movements that kept you streamlined and gliding. I was amazed how well that worked, as I was able to do the down and back many times. Even after leaving Tech, if I were at a large pool, I would test my ability to still do this, and I found that I could. This always amazed those who were watching, and it gave me great confidence to know that if ever I were faced with having to be underwater for an extended period, I could do so, as long as I practiced what Coach Nelson taught me.

Arthur "Art" Kunzer, Text 54

Took Coach Lanoue’s Drownproofing course in the winter quarter of 1951, 8AM Tues., Thurs., and Sat. I was a Red Cross-certified lifesaver, so I had no trouble with the course; I got an "A" in the course! I was surprised to see how many classmates were terrified of the water upon reaching college. Coach Lanoue taught us how to stretch our limits (swimming two laps with hands and feet tied), and I can still hear him yelling encouragement while underwater! He was truly a legend for all who “survived” his Drownproofing course!

Bill Brockman, Mgt 73

As I tell anyone who will listen, Drownproofing was by far the most memorable class I took in my four years at Tech. Imagine, a 1-credit hour class taken in the winter quarter of 1971, and 50 years later it is vivid in my memory. I had the great Coach Herb McAuley, and what a character! I am so glad to see his name honored at the 1996 Olympic pool facility every day when I swim laps there.

My story involves the underwater swim. The pool was 25 yards, and to pass the class, one had to swim one length underwater. To get an "A," one had to swim down and back without surfacing. To make it harder, we had to jump in and turn a somersault underwater to start without pushing off the end wall. We could push off the far end for the return length. We were allowed to hyperventilate before (which has since been banned as dangerous), which gave a real advantage. If one passed out and had to be rescued, that was also worth an "A." Before we were tested, Coach McAuley told us that “Every successful GT alum had gotten an "A" in Drownproofing, including astronauts." Test day, everybody passed, including me, except for two unfortunate young men who surfaced before completing one length. Coach went after them in a manner that would surely have gotten him fired today; he told them they could retest next session. Needless to say, both got an "A" by doing a full down-and-back! I was struggling academically that sophomore year, and it’s possible the one-credit hour "A" I got in Drownproofing is the reason I have a GT diploma on my wall today.

Earl Walker, AE 61

My most vivid memory is of swimming with my hands and feet tied, just after surviving for 45 minutes. I made it about halfway, but I was unable to get up high enough to get air and couldn't exhale enough to go to the bottom and push off. Eventually the coach who was watching pulled me up for a breath of air, and I continued the swim. I grew up on the beach in Florida, swimming almost every day, but I learned so much more from this experience. I didn't panic.

Al Berst, Arch 54

In the spring quarter of 1951, the U.S. Navy sent personnel to see Lanoue's drownproofing. Lanoue asked for volunteers in his classes, offering to let us skip the 1500-meter swim. The goal was eight hours — yes, eight hours. Some had their feet bound, some their hands. I chose not to be bound. The pool was crowded, but at about lunch time, it had thinned out. I got out after five hours. The Navy was impressed. This was life-altering for me, as it proved we could master our fears and remain vigilant. Lanoue was a true leader.

Mike Esterman, Chem 64, ABio 65, MS ABio 67

Winter of 1960 was my second quarter at Tech. I had already heard scary tales about the course and was apprehensive going in. The coach for my course was McAuley. I was a decent swimmer going in. I did not find the course intimidating at all and was glad I was able to take the course. I did get an "A." I regret that it is no longer a part of the curriculum.

David Paradice, InfoSci 78, MS IM 79

I think three students passed out on the underwater swim before my turn to do it. I came up about 15 feet short of making it all the way, and I have been mad about coming up for air that close ever since! In a class of about 23, six passed out during that test. My brother also took the class. I think every challenge we have faced since graduation has included at least a passing thought of “At least it doesn’t involve being tied up and thrown in a pool…” It was a challenging class, but that was expected. What I didn’t expect was the life-changing experience it would turn out to be. I took the class in the “old gym.” Every now and then, a ceiling tile would just fall into the pool. That just added to the class’s charm…

Ken Klein, IE 67

As I wrote in my autobiography, Boat in a Bottle, I “knew” Freddie Lanoue and read his Drownproofing. A Georgia Tech physics professor, he applied body physics to surviving rough water. I still have nightmares about being late for Drownproofing Class, a required Georgia Tech PT (Practically Traumatic) course. Mr. Lanoue was a gruff instructor with a weak leg (like my dad, who also built his upper body and was a strong ocean swimmer), who forbade us to be late or drown during his class. I tried to nap before class and wake up in time, before being tossed in the pool with feet and hands tied, float for an hour without touching the pool’s side or drowning, or swim underwater for 100 yards (or was it 1000 yards? I forget). I was a fair swimmer who did not panic. I scored 1100 out of 1000 points (100 extra credit for being on time, having fast lap times, and not drowning). I was pleased with my "A+," which helped me to stay in school and not get drafted (I was in Army ROTC).

Ken Roberts, BC 77

I actually took drownproofing TWICE. The first time was as a freshman in 1973, but I didn't complete it after I passed out with my hands tied due to a bad case of mononucleosis. I later took and completed it as a senior in 1977. Entering the course, I was a poor swimmer and lacked confidence in the water, so I struggled to complete many of the requirements. But after the course, and still today, though still not a great swimmer, I have confidence in the water. I think Tech should bring the course back.

Ray Pettit, EE 54, MS EE 60

We were "non-swimmers" in Spring 1951, separated from the freshman class of Fall 1950 to deal with our deep fears as a group. I have had many academic and professional accomplishments in my life of 88 years, but the "C" earned in Drownproofing is high on my list of things I pride most. We were featured that spring in a multi-page pictorial article in LIFE which had some students treading water for 12 hours. I wimped out after 3 hours. What memories!

James "Ken" Poor, ME 84

Before Drownproofing, I really couldn't swim. I waited until the end of my time at Tech to take it because I was so scared of water. On the first day of the class, they tied us all up and told us to tread water for several minutes. I just burst into tears, as did a few other scared people. Fortunately, they removed us from the class and put us into "Remedial Drownproofing." In the remedial class, they slowly introduced us to the water – we would gradually get into deeper water while jumping up and down in the pool. As the class progressed, they taught us basic swimming strokes and how to float so that when needed, we could lift our heads out of the water to breathe. They basically demystified water survival for me. By the end of the class, I actually jumped off the high dive. In retrospect, I feel it was the most life-changing class I took at Tech. I would have never taken it if it weren’t required, so I’m grateful it was!

Isaac "Ike" Lassiter III, IE 1968

The recent article about Fred Lanoue remined me of an exciting session in the pool at Tech. As one who could only dogpaddle, had never been able to float, and who would never just go swimming, much less take a swimming course, I was very concerned when I was told to stay in the water for an hour without touching anything but water and air. (I cannot remember who made me do this or when, but I thought that I had to do it to graduate.) After about 55 desperate minutes, I moved over and put my fingers on the side of the pool for just long enough to regain my strength and finish the hour. I have often told family and friends that I cheated my way through Tech, but did I? Was this required for graduation? Did I dream this story, or were other students of that era required to face the same challenge?

Robert MacKenzie, IE 62

Football scholarship students were not required to take course if we could tread water for 45 minutes. He threw me in the pool, and I didn't see anyone until he came back when the time was up. I grew up in Florida, so this was easy to pass.

Terry "Ted" Latimer, CE 69

One test was to swim the length of the pool and back with my legs tied together and hands tied behind my back. Then I had to do a front flip and a back flip while still tied. My leg ropes came loose before I completed the back flip. I had to do the whole test again! I did however ace the course!

Dan Mitchell, ChE 80

I was an entering freshman in the fall of 1976, and Tech was intimidating enough. Hearing the stories about Drownproofing was almost too much. On the first day scheduled in the pool, I realized I had forgotten my swimsuit (I was a commuter) and went to Rich's to find one. Of course, the only suit left was resort-appropriate with huge tropical flowers. I found myself surrounded by classmates in competition Speedos. The only thing that helped me fit in was how short the ghastly suit was (think Michael Jordan- or Larry Bird-length). I survived, and I have since never feared falling off a boat — as long as the water is well above freezing.

James Thomson, Phys 69, MS Phys 74

We were practicing in pairs, learning to push off the bottom of the pool with hands and feet tied. I was the spotter for my partner. He got stuck halfway between the surface and the bottom of the pool, so he couldn't reach the surface to get air and couldn't reach the bottom to push off. I could tell he was in trouble because of the way he was thrashing his body, trying to kick up to the surface. I jumped in and pushed him up so he could breathe. Needless to say, he was very grateful for my help. I don't recall the name of my partner that day, but I sometimes wonder what might have happened if I had been a little less attentive.

Stephen Vogt, EE 71, MS EE 72

I remember thinking, "What?!" when I heard about the three required P.E. classes: Drownproofing, track, and gymnastics. How can a person possibly learn any of these in three months and get a good grade? Anyways, Drownproofing turned out to be the easiest, except for the complete lap underwater swim — I only made it down and halfway back. The incident I remember best was when we had to jump in, fully clothed, inflate a life ring made from our pants, and hang out in the water until our name was called, the coach noting our success. Since my name is at the end of the alphabet, I was not called for a long time. I tied the pantlegs, inflated them, and came up for air for the first time. The coach was only a third of the way through students' names. My pants were leaking fast, as I could hear the PSSSSSS from the air escaping. I thought I'd better go down again and re-inflate my pants. I came up, and the coach was now halfway through the names. I held out as long as I could, but I was starting to sink. I decided I’d better add some air once more to impress the coach. This time, when I came back up, the coach was yelling, “Vogt, Vogt? Where’s Vogt?” I waved my hand, and he finally checked me off. I thought I wasn’t going to make it. I learned from Drownproofing that I could tread water indefinitely, from gymnastics that I could do so-called “tricks," and from track that I would never get any faster — all valuable lessons.

Albert "Richard" Bunn, Arch 73

I aced every test and skill, but not without a great deal of trial, error, anxiety, and stress. It was one of the best classes I took at GT, and it should be a requirement today.

Chi Lin Swift, Mgt 88

I saved Drownproofing for my last quarter. If I were to flunk out, I wanted it to be for another class. They announced that Drownproofing was no longer a requirement right before my last quarter. My friends ran to tell me, but I didn’t believe them. I demanded to see it in writing, and I felt relaxed only after they showed me the campus newspaper.

Hiram Allen IV, IE 85

Having swam competitively since I was a six-year-old and working summers as a lifeguard, I jumped at the chance to sign up for Drownproofing as a freshman. After scoring a 100, my instructor encouraged me to become a TA, so I ended up "taking" Drownproofing at the Old Gym each quarter after that. Great experience. The first week was always the toughest, as we discovered who needed to drop the class and take beginner's swimming, usually by pulling them up off the bottom of the pool. I would get them to the side of the pool, and the instructor would hand them a drop slip.

Joseph "Hank" Griffith, Mgt 89

As an Army ROTC scholarship recipient, it was "highly encouraged" that we take the P.E. class. I remember swimming the length of the pool with a rubber brick around my neck and learning how to inflate my pants to use as a life preserver. The basketball players had the worst time in the class, as they were all muscle and had no body fat. I remember the quote of "Fat floats, muscle sinks." I can't believe they don't offer the course anymore. I loved it.

Richard "Rich" Weissinger, IM 77

I had just completed and passed Drownproofing, the arduous rite of passage, and I felt invincible in the water. Quite out of my normal routine, I dropped by the pool for an evening dip with a buddy. I dove in from the poolside, and bam! I had hit my forehead on the bottom of the pool. Stunned, I swam back to the poolside and started pulling myself out. A young lady happened to look down at me and screamed as she walked by. I was bleeding a lot. Eleven stitches were required at the Tech infirmary, and afterwards, the doctor shaved my hairline back. Nature took care of that hairline later. After graduating, I was commissioned an ensign and went through flight training with the Navy. This included quite a lot of swimming, but nothing the Navy threw at me was close to what we had at Tech. The scar remains as a reminder.

Jim Ford, ChE 68

My first P.E. course at Tech was during my first quarter, and I loved it. Drownproofing taught the power of self-reliance and determination. I proved this to myself when I swam up and back underwater, only on what air I had in my lungs when I began the swim. I proved this again when I jumped off the high board with hands tied behind my back and feet tied together, then made to drownproof for a few minutes. I got an "A" in that class, and I was proud of it. Freddie was a great man.

Aubrey Bone, IM 80

I was so worried about this class that I put it off until almost my last quarter! I finally talked myself into taking it, reasoning that the instructor would gradually get us prepared to do the hardest stuff over the course of the quarter. Little did I realize that by week three that we would have already done all the hard stuff! The rest of the quarter was just playing water games, a totally great break from study! It was a great life lesson that our biggest obstacles are the ones we create in our own heads.

Albert "Chuck" Musciano III, ICS 82

For my four years at Tech, I dreaded the thought of taking Drownproofing, better known as PE 1010. This is a terrible thing to admit, but I often thought that if just one student would drown in the class, they'd cancel it for the rest of us. Regrettably, no one "took one for the team," and I found myself in PE 1010 during the final quarter of my senior year. While I am no swimmer, I earned a "C," survived 20 minutes in the water with my ankles tied, and came away, as intended, with a newfound confidence for my ability to survive in the water. My son (ME 17) did not take PE 1010, and my wife (IE 82) and I often point out that Tech was harder back then due in no small part to PE 1010. Looking back, my fears were unfounded, and the course was a valuable part of my Tech education. I wish they hadn't dropped it as a graduation requirement; it is part and parcel of the history of our great institution. As we often tell others, "If you make it through Georgia Tech, you know that there is literally nothing else you cannot do." Surviving PE 1010 was part of my experience that I wouldn't trade for anything.

Lance Campbell, MgtSci 88

My class was the final class ever required to take the course. I found it to be enjoyable and challenging. I still tell friends the (true) tale of how we had to "swim" (bob) three lengths of the pool with arms and legs tied, with a weighted brick around our neck. #LivedToTellTheTale

Robert Irvin, EE 87

We were doing the test where you hold the weight above your head and kick to stay afloat for a minute. We watched the instructor do it for about ten seconds, upright in the water using a "rotary kick" to stay afloat. He made it look so easy. Just about everyone in the class tried to do this, and no one succeeded until it was one girl's turn. She got on her back, put the weight on her head, and managed to kick around for a minute. Everyone, especially the guys, was so upset after they saw how relatively easy it was with just a couple of tweaks! It was definitely some out-of-the-box thinking!

Robert Probert, IM 57

To get an "A," we had to swim the full length of pool underwater and return OR pass out underwater. My friend said, "Bob, I am going to get that 'A'," and he sure did. When he passed out, they pulled him out, and he was okay. There were 42 students in the class, and Freddie said, "Two of you cannot float." I was one of the two. I am disappointed my daughter ('87) and granddaughter ('22) did not have to take the Drownproofing course.

William "Bill" Bulpitt, ME 70, MS ME 72

I had learned how to swim in the cold water of Long Island Sound when I was five years old, so I came to Georgia Tech as an "adequate" swimmer. As a first quarter freshman, I was taking 19 credit hours, including ROTC, so I felt like I was carrying a lot of weight. A little extra weight was added by taking Drownproofing, however. We were required to do many things that were just not natural. To be honest, many of those things are etched into my brain, and if I ever did have to save myself in a water emergency, they would be useful.

When I was preparing to take the underwater "test" (two laps in the long pool underwater), I was waiting in line and watching a guy two or three people ahead of me. He made one lap down, turned around, and came back, and we watched in horror as he bumped his head at the end of the second lap. He was down pretty deep, but he just kept his stroke going. He had essentially passed out and did not know where he was. Coach McAuley and another guy jumped in and fished him out. They did not give him mouth-to-mouth, but it took a while for him to come around. It suffices to say that when they got around to re-starting the "test," I had seen enough — I made it one and half laps before I threw in the towel. I did not want to repeat what the other kid had just done. Just another humbling incident in a very humbling quarter...

Louis Wells, Phys 60

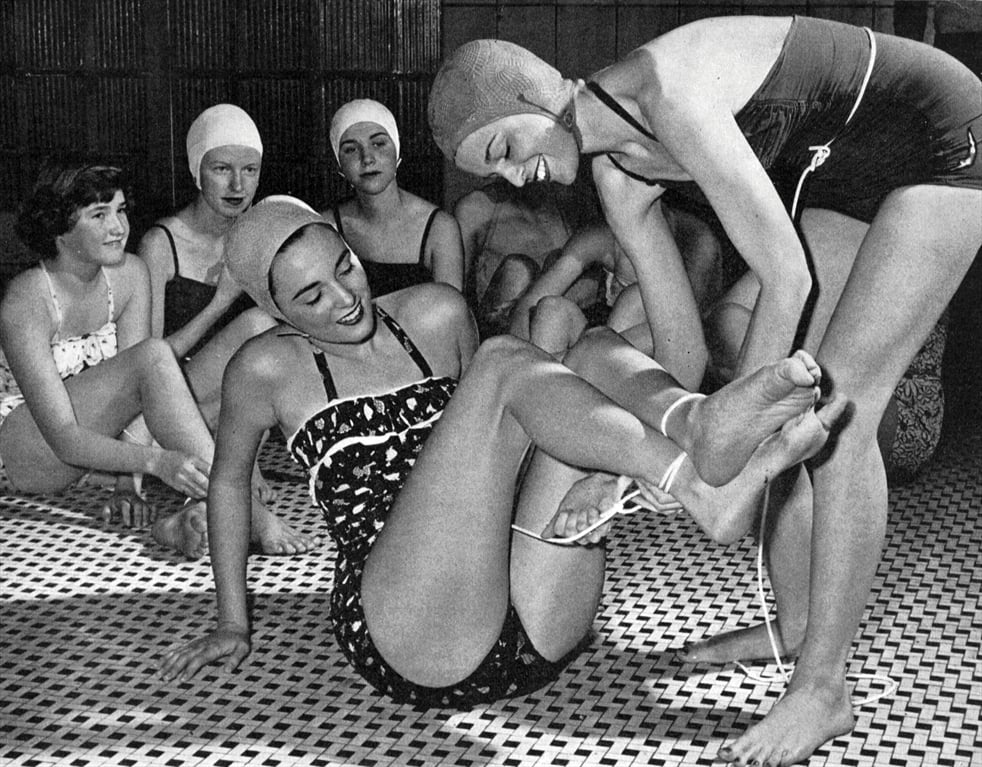

The idea that Tech "offered" the course is a bit misleading. It was required unless you were a veteran or had a medical excuse. We weren't allowed to float with hands and feet tied: rather, we bobbed. If you came in as a non-swimmer, you could pass the class by staying up 45 minutes with only your hands tied, floating only on your stomach. And the photo in the article must not have been taken at the Tech pool when I was a freshman because swimming was allowed only nude. The excuse was that lint clogged the pool filters. Believable?? This is, of course, all from memory.

Joel Alterman, AM 66, MS IM 69

Believe me, I’m the furthest thing from an athlete you ever saw. But I loved the Drownproofing class. In order to get an "A," you had to do turn routines that progressively got harder. The final and most difficult routine required you to jump off an high dive platform with your hands tied behind your back and your ankles strapped together. Then you had to maneuver yourself to the deep end and retrieve a black rubber ring with your mouth! After accomplishing that, you had to stay afloat for the rest of the one-hour class with the rubber ring in your mouth. Well, I did it, and I still remember the horrible taste of that rubber ring. Coach Lanoue was obviously a very special person and a real gift to Georgia Tech.

Robert Jenkins, IM 68

I got extra credit for swimming backwards the length of the pool, all underwater.

Marilyn Smith, AE 82, MS AE 85, PhD AE 94

This was the most enjoyable (and easiest) "A" I had earned at Georgia Tech. My clearest memory is one where Coach McAuley made me stop treading water with the brick over my head after class ended. I wanted to keep going, but he said I already had the longest women's time he had ever seen. Great and important class. I was disappointed when it was discontinued; this is a course everyone should take.

Stephen Fleming, Phys 83

I think Drownproofing has an enormous amount to teach us about developing "grit" in our graduates, which is especially valuable in an entrepreneurial world.

Thomas "Jim" Pierce III, Mgt 90

When I was at Tech, we had the quarter system. I was told that the last quarter of Drownproofing was coming up, and I had not yet taken it. I did recall lots of crazy stories about it from my father, and I wanted to connect to him and Tech history through this class. I signed up, and the class was in the old Heisman Gym. We were told there were two ways to make an "A": score above a 90 in the class or be hit by a piece of the falling ceiling tiles while we were doing laps in the pool. Lots of people did their backstroke slowly, looking for loose tiles. I don't think anyone got hit or even saw a falling tile...

Joel Greenberg, Arch 67

As a first quarter freshman, the course was described as "swimming," but it was way more than just "swimming." Swim two lengths of the pool in the old Navy gym... with your hands tied behind your back and feet tied together. Swim two laps of the pool, continuously, underwater... Pick up a rubber ring off the bottom of a 15-feet deep pool, with hands tied behind your back and feet tied together. Tread water for at least half an hour, tied just the same. Jump off a 10-meter diving board. This was a required course to graduate, a real test of your "internal fortitude." A great experience that made the rest of the "Tech experience" seem easier!

Daniel Leithauser, Chem 85

I took Drownproofing as literally my first class at Georgia Tech: fall quarter of 1980, at 8am. I knew how to swim and took lessons when I was a five-year-old. Swimming competitively in a Florida middle school, I felt “prepared." What I learned in those classes was valuable to me later.

Notably, do not panic and preserve natural buoyancy. While multiple experiences stood out, including almost drowning in the “tied hands and feet, thrown in the water” task, I always thought the best one was having to swim two laps underwater. Coach McAuley told the class, “I am going to tell you the secret to doing this test." We all thought it was hyperventilation. Then, he jumped into the water, and from a dead start, with nary an extra breath, he swam from one end of the pool to the other and back to us, underwater, with ease.

“Did you see what I did? Consistent, slow, and clean strokes, with long glides in between… stroke, glide, and stroke again. Watch the bottom of the pool go by. This will take you easily to the other end, then when you turn around, you will feel hungry for oxygen… Just remember that two strokes will take you halfway across, and then just two more to the end. This is not a race. If you try to make it a race, you will fail, because you will use too much oxygen.”

Watching him do it, then understanding how he did it, the class completed the task one person at a time. Only one person came up, gasping for air in the middle of the pool… The rest of us all passed. It was an enlightening moment. “Demonstrate the task to teach," McAuley would say. To this day, I watch movies with people frantically swimming underwater, running out of oxygen, and think to myself, “You are doing that wrong!”

Miguel Avila Jr., IM 81

The week before fall quarter, I had been snorkeling for almost seven straight days with five other GT students. On the first day in the water, I held my breath for 3 minutes and 59 seconds and only came up because I heard so much yelling. Coach Decuba asked if I was alright, and I told him that I was fine and only came up because of the yelling. He then asked if I were human. I'm wondering if I have a record for that class in holding my breath.

Vicki Myers

I somehow landed in a class with the entire GT football team! When it came to dragging someone many lengths in the pool, I got chosen every time. But when 110-lb. me had to do it, no one matched my size. I had to drag the coach.

Lyle Latvala, AE 66

For our final exam, we had to swim underwater for a lap and pick up a brick from the deep end of the pool. I jumped in, feet first, and accomplished the task. However, Coach Lanoue said that I should have lowered myself into the water to ensure that I didn’t hit an object that might be there (like it were a lake instead of a pool). Taskmaster! He gave me a "B" on the final exam, but I still aced the course, as I had "A's" on all the exams up until then. I admire Fred Lanoue to this day.

Michael Langston, CE 89

The pool area was extremely cold during that winter under the north end of Grant Field. Swimming was not a challenge, as I grew up in Florida. Making floating devices out of shirts and pants was fun. Swimming the width of the pool with both hands and feet tied was, however, a challenge. It was a fun class with life-saving techniques added at the end. It should have remained a requirement just to differentiate GT from other schools.

Chaz Cone Jr., IM 61

One of the old idiosyncrasies of Georgia Tech was that every student had to pass PE 103 -- or fail to graduate. PE 103 was entitled "Drownproofing" and consisted of learning several swimming skills, which, if mastered, would ensure that you could stay afloat/alive in the water indefinitely. It was the brainchild of Tech swimming coach Freddie Lanoue. …I wasn't any good at sports (except maybe for bowling), but I was a good swimmer, so I volunteered to be in the teaching group. So the two or three of us would get the skill presented by Coach Lanoue, we'd master it, and then we'd teach it to the rest on the next class day. Drownproofing is a well-respected, internationally taught set of skills that has saved hundreds of lives. If you can do it, you can save your own life when unexpectedly cast into the water. As we learned these skills, I was doing well, until we came to one a little past halfway through the course.

Here's how it worked: Your hands are bound behind you with rope. Your legs are bound together at the ankle with rope. Another short rope connects your hands and your ankles which forces your body into a bow. A rubber ring (about six inches in diameter) is tossed into the water at a depth of ten feet. You are tossed into the water. The task is to make your way to the bottom, grab the ring between your teeth, and make it back to the surface. Hands and feet bound together behind your back. Easy. I had no difficulty making my way to the bottom; all you have to do is provide enough movement to counteract your natural buoyancy.

I found the ring, but when I opened my mouth to bite it, both my eardrums popped. It didn't hurt much, but one of the functions of the eardrum is to keep the middle- and inner-ear dry. If they get wet, one becomes disoriented. The sides and bottom of the pool were all thoughtfully painted white, so I really couldn't tell which way was "up." Of course, my companions above had no way of knowing about my distress. Oh, and all the while I'm using up the big breath I took about a minute or so ago. Somehow, someone noticed my distress and reached down with a hooked pole to pull me up. They rolled me onto the pool apron and did what they could to get the water out of my lungs. That part went well, but I couldn't hear a thing.

I went to the infirmary for a diagnosis, and that's when I learned I had two perforated eardrums. I was sent to an ENT specialist, and as I recall, he did some kind of patch involving tissue paper and glue. The eardrums healed, but consequently, I have had a high-frequency hearing loss since then. The bright spot to this story: I failed my induction physical because of this, and I never had to visit Vietnam.

Milton Leggett, IM 63, MS IM 70

I'm proud of my "A" in the required swimming course under Coach Herb McCauley in 1960. The very next summer, I was fishing near the jetties at Fernandina Beach in a backwater area. A family started crying out for help, when their 13-year-old son ventured into water too deep for his abilities. I ran down the beach and swam out quickly, put him in a cross-chest carry that I learned at Tech, and swam back to shore realizing the family most likely could not have saved his life. The Drownproofing course taught lifesaving of others as well as saving your own life. That training kicked in just when needed. Later in life, I became a Red Cross Water Safety Instructor and taught classes in lifesaving to explorer scouts. The lessons at Tech gave me confidence around the water that I carried throughout my life.

Grady Thrasher III, IM 64

During my freshman year at Tech (1960-1961), Lanoue's course was required for all male students who did not have an acceptable medical excuse. To receive a passing grade in "swimming," as we called it then, each of us had to navigate underwater the length of the pool and back without coming up for a breath. If a swimmer passed out in the effort, and some did, someone would fish them out with a long pole. But their passing out ensured a passing grade, usually an "A." One classmate attempted the feat many times, but his body was apparently too buoyant for him to remain underwater long enough to complete even a short distance. We all encouraged him with each effort, but it seemed he was doomed to fail the course. Then, to everyone's amazement, on the last day of the term, he showed up with two heavy concrete blocks, secured them to his body, took a deep breath, and did a determined walk underwater for the entire length of the pool. He turned around underwater and slowly walked back without surfacing. He emerged gasping, but with a smile, to cheers from the class and from Coach Lanoue.

Kevin Guske, IE 89

I started the co-op program in the spring of 1985, and I decided to take Drownproofing that summer. It was required, so I figured I would get it out of the way. The gym was so old that pieces of the ceiling were starting to fall, and I learned later that might have been at least part of the reason "Ma Tech" stopped requiring it.

On the first day of class, we were told to swim the length of the Olympic-sized pool and back as fast as we could. John Dewberry, who was known in part for being a great scrambling quarterback (our offensive line was a bit weak that year), was in the first group. He was down and back before most people reached the first end!

Part of the final exam was a scenario in which you were on a burning cruise ship with burning oil on the nearby surface. We had to jump off the high dive, fully clothed with a swimsuit underneath, then swim underwater to the shallow end. Once you got to the shallow end, you had to take off your pants and use them as a flotation device. I went before John, but I saw him nearby in the shallow end.

"Hey, what do I do?" he asked. I told him to take off his pants and blow air in them to float. "Yes, I know," he replied, "But I'm not wearing anything underneath!" We laughed, and he somehow figured out how to add air without removing his pants. He could scramble in a pool, too!

I wasn't a great swimmer, and the things we had to do in that class were pretty scary. For example, we had to swim three lengths with our hands tied behind our backs, had our feet tied, had our hands tied to our feet, and even had a 10-lb block around our neck (I made it 1.5 laps before some hands yanked me out as I collapsed). But it was all required, so I had no choice. This class, probably more than any other I've had, taught me confidence. If I could overcome the many challenges of Drownproofing, nothing could stop me.

John "Jack" Carswell Jr., Phys 66, MS NE 68

As a freshman in 1962, I had to take Lanoue's course. Since I had been in the band in high school, I had never had to take ANY P.E. courses, so the ones I had to take at Tech were eye-openers, but none so much as Drownproofing. I can't say that I ever really liked Lanoue, especially because of the experience I will describe below. However, once I completed the course, I definitely respected Coach Lanoue, and I treasure the time spent in the Tech pool.

Although definitely not a competitive-level swimmer by any stretch of the imagination, I nevertheless fancied myself a decent swimmer, and in fact, I was. I pretty much sailed through all of the early tests, and I couldn't help but laugh at those "kids" who were actually too scared to jump off the high dive. But then came the underwater swim. I actually thought I wouldn't have any problems with that one either, but boy, was I wrong.

I had no problem at all with the first length of the pool, and the turn was easy as well. But then halfway through the return lap, my mind took hold of me, and I started coming up. I can still hear Freddie to this day, yelling to me, "Don't do it, sucker. You can make it. Don't you dare come up, sucker. SUCKER, SUCKER, SUCKER!" Unfortunately, I did come up, probably on ten yards from the finish, and I hate myself for it to this day. And I HATED Lanoue for yelling those things to me. Because of that failure, I made a "B" in the course; otherwise, I would have aced it. I hated him, and I hated myself, but all these years later, I totally respect the man. I consider that course one of the most valuable courses I ever took.

Steven Susaneck, ABio 73

Even the swim team had to take it!

Robert "Rob" Thompson, Phys 84

My most memorable Drownproofing story concerned having both hands and feet tied together, along with a 10-lb. weight tied around my neck, then being placed in water a few inches over my head. The idea was to bob up and down off the bottom for 45 minutes or so. Unfortunately, as the tallest person in the class, I was lined up towards the deep end, just where the pool sloped down towards the diving boards. I bobbed up and down just fine for a few minutes, not realizing that every time I kicked off the bottom I was moving a little closer to the deep end... Finally I kicked strongly off the bottom, went up a couple of feet, and then stopped a few inches from the surface. Fortunately, it was easy to get out of the ropes, but not making the full 45 minutes cost me an "A" in the class.

Ann Harris, EE 81

At some point in the class, we had to go down to the bottom of the deep end, with clothes on over our suits, hands tied, and then to float to the surface. While practicing this, I sank to the bottom and found that I could not rise. Nobody was watching me, either. I ended up bouncing off the bottom of the pool and propelling myself upwards. When still quite a way from the top, I could no longer hold my breath. I opened my mouth to breathe and ended up swallowing a big mouthful of pool water. But alas, I made it to the top and survived. NO ONE NOTICED that I nearly drowned.

Andrew "Andy" Fisher, ME 82

The course probably saved my life. I was swimming out to a boat from the shore and was running out of energy. I got a cramp, and the boat was farther in the water than it looked from land. I did the dead man's float for about ten minutes, got my energy back, worked the cramp out, and later made it to the boat. The funny part (well, funny now) was that someone from shore had been swimming to me with a life ring, as they thought I was drowning. They turned back when they saw I was swimming to the boat again. I was about 23-years-old and had only been graduated for a year.

Christopher "Chris" Squires, CE 87, MS CE 88

Drownproofing was still a mandatory class when I started at Tech. The course itself seemed a bit strange; for example, it taught us how to stay alive with our hands tied behind our back and how to make a life preserver out of our pants. The real drownproofing story for me came nearly twenty years later, when I was involved in what the hospital classified as a marine accident.

I was knocked off of a pier, down a set of rocks, and underwater by a rogue wave. I was blessed to avoid hitting my head on the pier, railing, or the rocks, but I did have all of the air knocked out of me and was pretty torn up. By the time I realized what had happened, I was underwater, desperately wanting to breathe, with no idea of which way was "up." That was when the most important lesson of drownproofing kicked in: relax.

I didn't know if I would make it in time, but I knew that my fat would carry me to the surface if I simply relaxed and waited. By virtue of being able to write this, you can surmise that I retained consciousness long enough to survive. While I don't think Drownproofing should be a mandatory class, it would be great if students today had the opportunity to take it. In addition to water survival skills, the course taught a bigger life lesson about keeping composure even in moments of crisis.

Jane Pierce, IE 82

My class consisted of me and twenty-three guys. The last test was to swim the length of the pool and back in one breath. I knew the guys were all watching me closely, so I decided I would not come up until I completed both lengths. Coach said if you passed out, you'd still get an "A," so I figured one of those guys would rescue me before I drowned. Nevertheless, through sheer determination, I made it!

Richard Maugans, ChE 70

I did the whole Drownproofing thing. I was already a decent swimmer, so it wasn't too hard. However, I really dreaded the test for doing two laps underwater one a single breath. I practiced a lot, but I never could quite make it. Then, on the test day, I just jumped in, did my flip, and swam with everything I had. I got all the way down and back to the deep end, swam up to the surface, and reached over to touch the side.

"NO GOOD, KNUCKLEHEAD! You have to touch the side while still under water," said the coach. I was so frustrated, mostly with myself. I limped off to the shower room and had a short talk with myself; then, I decided to go find the coach and try again. To my great surprise, I actually made it! So I ended up doing the test twice within an hour. To this day, I still remember what this taught me about not giving up and pushing past what you think your limits are.

Jack Nichols, IE 66, MS ME 74

I could not swim and had no interest in learning. However, the curriculum required passing the Drownproofing course in our freshman year. I did not appreciate it then, but in later years, I have really appreciated the ability to survive should the need ever arise. Another great memory from Georgia Tech!

Patrick McNew

One of the tasks was the underwater swim. You had to hyperventilate and then enter the pool in the deep end with a summersault. Lanoue taught us to frog kick and pull with long glides to make it two lengths of the pool without surfacing for air. We had a student who flipped in and began sculling with his hands at his side and flutter kicking. Lanoue walked alongside him, screaming, "Frog kick and pull!" at him with lots of colorful adjectives. The guy completed two lengths with no trouble, and he then turned and did TWO MORE lengths using the frog-kick-and-pull technique. Lanoue was speechless. It seems the kid was an experienced snorkeler from Florida.

Murray Brinson, ME 67

My first quarter P.E. class was Drownproofing. It was a wake-up for an already good swimmer. The test that almost got me was the underwater lap of the pool, and Freddie "The Fish" cracked up!

Michael Tennenbaum, IE 58, HON PhD 16

I did underwater swim my first try. When I surfaced he yelled, “sucker your feet didn’t hit the water first you do it again.” Too which I foolishly replied, “you [a**hole].” He said nothing back. I did the swim again and he counted it. He was a great man.

Paul Ternlund, EE 65

Fred was my swim coach. I was a breaststroker on the swim team for 4 years. I never practiced the underwater swim, and I feared it. My class was extremely well taught by Coach McAuley, and I deemed it valuable. I recall a member of a Navy UDT Team visited poolside once. I think he lost a hand in his service and came to tell the class about it. Anyway, when it was my time to do the underwater swim, I did it faster than I my best time on the surface! I have taught my kids drownproofing. Fred was special and is missed.

James "Jim" Murphy, IM 70, MS IM 76

I quickly found out that I was a "sinker" totally dependent on the air in my lungs. During the underwater round trip of the pool, on the return leg I started noticing that I was getting close to the bottom, which was confirmed when I closely passed over the pool drain. I touched the wall at the bottom and had to swim upward toward the surface, and two guys reached down into the water and pulled me up. This got me a "B," and the coach said that if I want an "A," I would need to jump off the high dive. Conquering, slowly, my fear of falling, I reached the end of the board and jumped. I was surprised how hard the water felt when I hit, but I got my "A," which I am still very proud of. Tech should re-start drown proofing as so many lives have been lost to drowning.

Wayne Daley, ME 80, MS ME 82, PhD ME 04

When I started in the Fall of ‘76, I heard stories about this drownproofing course repeated with much dread. I decided to take it earlier than later and registered in the Winter quarter of 1977. One of the coldest winters on record. Walking back from the Old Gym to my room in Harrison, my trunks were always frozen solid.

Our teacher was Coach Carlos DeCubas. On the first day of class, there were 20 or so men and two women. Turned out the women were Navy ROTC, and the class was required for them but not for the other co-eds. His first instructions were 20 laps warm-up. I thought he was nuts. I was comfortable in the water but not a strong swimmer. I was the only one that hesitated. Everyone else was off looking like little motorboats (found out later almost all swam for their high school). As I am making my way along the length of the pool, I can see the coach's feet walking along. When I completed one length he yelled, "You, what do you think you are doing?" I said, "Swimming." He said, "That's not swimming." He then told me to get out of the pool.

The end of the story was that for a part of every class that quarter, he took time to teach me how to swim. He taught me the crawl, breaststroke, and sidestroke as the ones most amenable to survival in the water. I went on to make a "B" in the class and took lifesaving with him the following quarter. Favorite thing to do was to say, "Most people float and some don't, jump in, Wayne." Stayed in touch with him. For those that might not know, he was a Cuban swimming and diving coach, and he also coached Jennifer Chandler, who won a gold medal in diving at the 1976 Olympics. I always felt that it was really kind of him to do what he did, and I have always been appreciative.

Shawn Doughtie, AE 88

During my time at Tech ('84-'88), drownproofing was required for graduation, and the overwhelming majority of students seemed to dread taking it and would hold off to the last possible quarter to take it. This meant that other students who wanted to take it — like myself — were effectively prevented from doing so early in their time at Tech due to graduating seniors having priority. When I was finally able to take it, I found it interesting, fun, and actually quite easy. It was also quite helpful at USAF water survival training! The one thing I have to dispute in the article is the statement, "Drownproofing was listed in Tech's course catalog until 1986." I know memories can be fallible (and I don't have my records at hand), but I am almost certain this is incorrect. It was definitely available past '86, and I know I took it in late '87 or early '88. I'll be happy to be disabused of these notions if proof can be provided!

Richard "Rick" Griffeth, IM 70

It was toward the end of the course, one of the ROTC boys came in dressed in fatigues, including combat boots. He proceeds to climb up the high dive and jumps in, sinking to the bottom. He then WALKS along the bottom to the shallow end to the applause of everyone, including the coach.

Donald "Don" Sanders, ME 82

I entered GT knowing about drownproofing from my 2-year-older brother. He got halfway through the class, then broke his collarbone playing lacrosse and had to start over the next quarter. My fraternity brothers had hyped the class to us underclassmen, so there was some encroaching anxiety. I was a lifelong swimmer and headed in with confidence. We all know the routine, class meets twice a week, you learn and practice the technique on the first day, and then get tossed in the pool for an hour of survival the second day. Then my turn arrived.

Week one on Tuesday, we learn to bob in the water with arms and legs tied. Pretty daunting for week one, but I think I have it down. By Thursday, I have developed a sinus infection, but go to class and give the test a try, and simply cannot breathe as required and I bail out. Over the following five days I'm haunted by the failure... Was it sickness-induced, or did I lack what it takes to master this class? Fortunately, the next week I’m well again, and after the first 5 minutes of anxiety of being rope-bound in the pool, I fell right into rhythm and never looked back.

Working for GE, I’ve had many colleagues who joined GE after long military careers from various branches. Without exception, they are blown-away at the GT drownproofing curriculum and agree that it’s comparable to their advanced training. The lesson learned and overall class intent was clear… These drownproofing tasks were a balance between physical technique and mental fortitude, with no room for lack of focus. My favorite bragging point is having successfully completed the two-pool length underwater swim without surfacing. I haven't tried it again since 1983, as I don’t want to sully my A+ resume.

Monica Mastrianni, Arch 82, M Arch 86

I don't remember a great amount of detail of my Drownproofing class, except for a few fleeting images: hyperventilating prior to a lap underwater without coming up for air, 20 minutes with my hands tied, just using my legs to swim, the same with having my ankles tied and just swimming with my arms, the "dead man's float," floating with my clothing blown up by swinging jeans and blouse overhead to catch the air, big strapping football players in my class petrified with apprehension at what the day's activity might be... Looking back, I am certainly thankful that I grew up learning to swim at the YMCA and had a comfort in the water that many did not have by the time they arrived at Tech. I never thought of the Drownproofing class as a torture, as much as we moaned and groaned. I did have the perception that it was being taught with care and concern for our self-improvement and with an understanding of the power of determination and what could be accomplished, in all aspects of our lives, when we acquired and harnessed it.

Arthur "Ted" Walker, CE 75

Took Drownproofing from Coach Herb McAuley. He taught us how to expel air with our face horizontal in the water so that a bubble of air would be caught over our eye and we could read underwater, at least, looking down. Coach McAuley was asked why we had to take Drownproofing (it was required of all students at the time), he stated that when we graduated from Georgia Tech, we would be smarter than the average Joe, and that should not be lost in a simple drowning accident. The thing I still remember to this day is the 50-yard underwater swim. It was at the end of the quarter, and we all knew, all quarter, that it was coming. We asked Coach about practicing for it, but he would not let us do that in the pool. He advised if we wanted to practice, we could time ourselves holding our breath while we were sitting around in a calm social situation. He stated that if we practiced in the water, we would only practice quitting because it was not the real situation. Concerning fortified mental fitness, we spent three times as much time on the benches outside the pool with McAuley admonishing, encouraging, and instructing us, as we did in the water. Concerning the 50-yard underwater swim, McAuley advised to concentrate, as we swam, on the tiles on the bottom of the pool, therefore taking your mind off the task at hand. Living in Florida, I spend a good amount of time in the water. There’s not a single time that I’m in the water that I don’t think about Drownproofing class and the confidence that it has given me. To that end, it may have been my most influential course at Georgia Tech.

Fred Ehrensperger, ME 54, MS NE 60

When I entered Georgia Tech in the Fall of 1950, non-swimmers were asked to put off taking P.T. 101 "Swimming" until the Spring quarter. I managed to get through P.T. 103 "Track" with no problem. P.T. 102 "Gymnastics" was a real obstacle, but I passed by doing the rope climb using arms only on the last day of class.

But P.T. 101 "Swimming" was another matter. Not only was I a non-swimmer, but I was afraid of the water, having had a bad childhood experience. On the first day of class, as we stood there in all our nakedness, Coach McAuley told us that if anyone came to the next class with hair below our eyebrows, he would personally correct that. I have had a crewcut ever since.

The first hurdle was the one-hour "bobbing" test, which I managed to pass. Later in the quarter, we learned to master Coach Lanoue's method of treading water. I also managed that technique OK.

Toward the end of the quarter, Life Magazine came to the campus to do a feature on Coach Lanoue and his drownproofing technique. The plan was to have a group tread water for 8 hours. Those of us taking swimming that quarter were encouraged to volunteer for this endeavor, which would provide more credibility to the Coach's technique and would also help with our grade. Needing all the help I could get, I volunteered.

We started early one Sunday morning. I believe we had 100 in the pool: 30 with hands tied, 30 with feet tied, and 40 in my group with neither tied. We all jumped in, encouraged by the words, "The eyes of Tech are upon you." After we had been in the water a little while, the Life photographer wanted everyone to move toward the middle of the pool so he could maximize the number in his picture. I could tread pretty well as long as I had plenty of room, so I tried to stay on the edge of the group. However, I ended up in this mass of bodies. I would go down and kick my way back up, wave my hands, pat myself on the head, and go back down trying not to pull anyone else down with me.