The first homecoming at Georgia Tech took place on June 7, 1920 and was sponsored by the Georgia Tech Alumni Association to celebrate the reorganization of the Association. The day featured a barbecue on Grant Field, a baseball game between students and alumni, and a banquet at the Ansley Hotel. According to newspaper accounts, alumni came from as far as New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Canada. Today, the annual event is planned around a home football game.

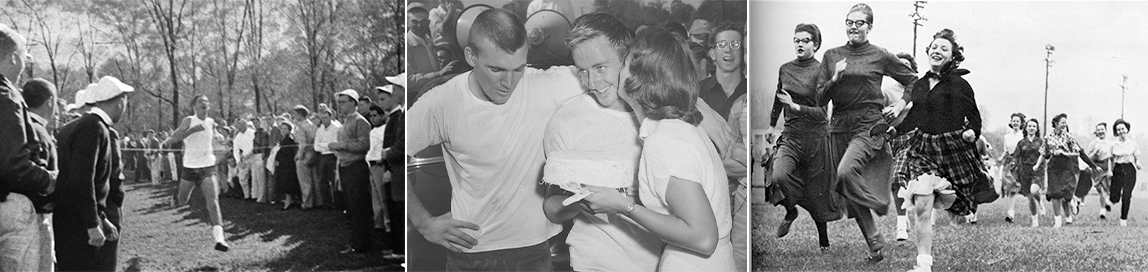

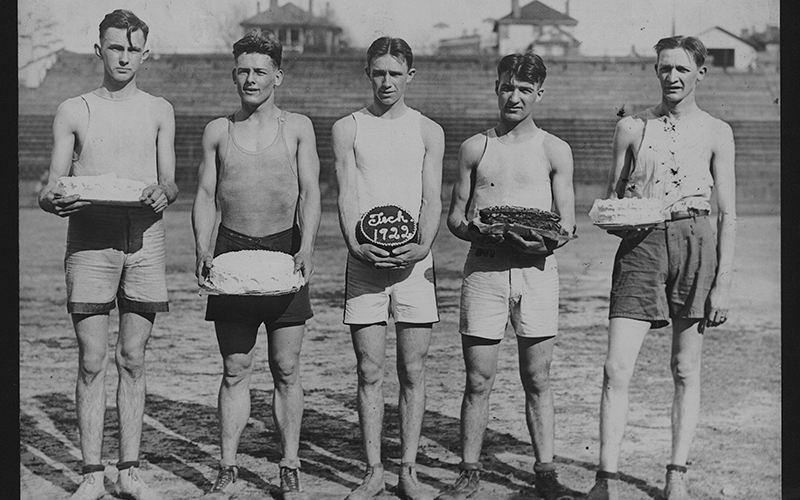

Freshman Cake Race

The freshman cake race earned its name in 1913 thanks to the tasty prize delivered to the winner. By 1935, the race was mandatory. These days, it’s optional, but any first-year student willing to wake before dawn to participate in the co-ed, half-mile sprint earns a cupcake. The top male and female finishers earn a full cake.

- The early course was around the Atlanta Waterworks area and was between two and four miles in length, changing a bit from year to year.

- When George Griffin was the track coach, he scouted the race for team candidates, turning "country boys" into track athletes.

- In 1953, after women came to Tech, the co-eds were exempt but ran a 100-yard dash instead.

- In 1954, a Homecoming queen was elected and a kiss from her was an additional prize for the male freshman winner.

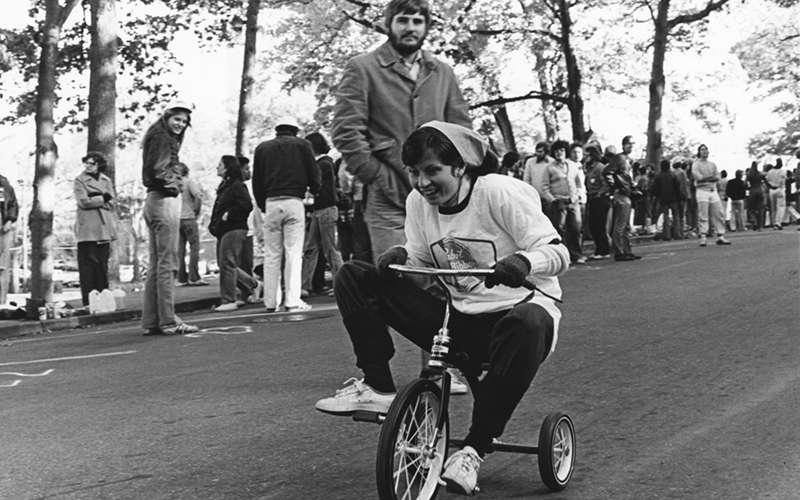

The Mini 500

The Mini 500 tricycle race attracts over 50 teams of seven vying to finish the 10 or 15 laps around Peters Parking Deck first. Engineers’ skills are put to the test: What’s the best way to reinforce a trike designed for toddlers? How can the pit crew shave precious seconds off of required wheel changes? And most important: What’s the best way to highlight a strong performance on a job resume?

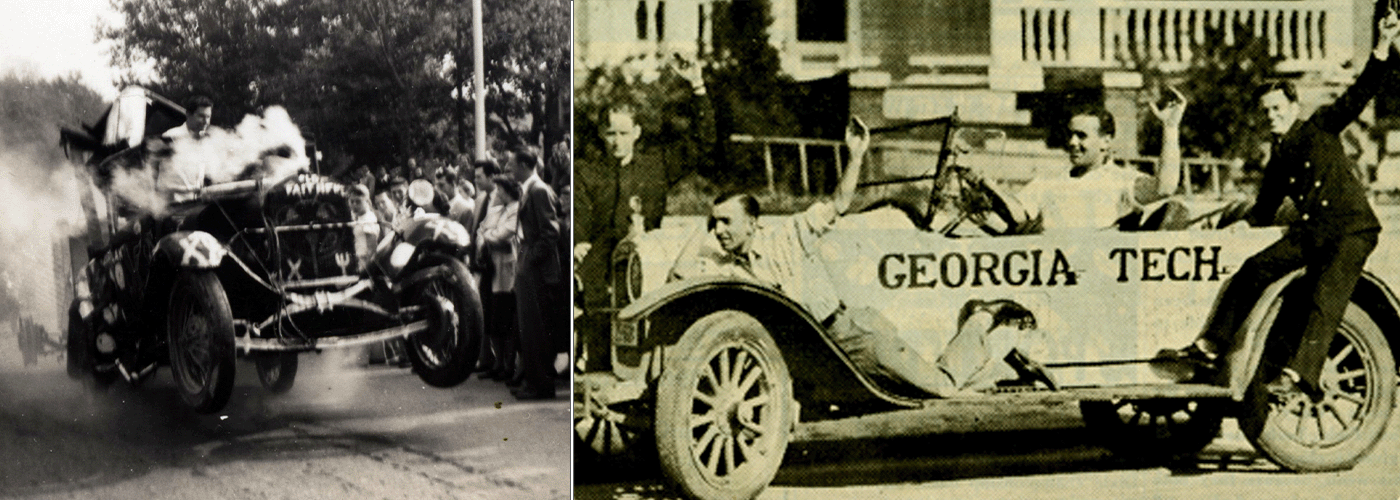

Ramblin Wreck Parade

Since 1932, the Ramblin Wreck Parade has been an ideal venue for students to showcase their engineering ingenuity. The parade features classic, themed, and contraption cars that get judged on both creativity and effectiveness. Past entrants have included some remarkable vehicles, from a spinning water cyclone to a Scooby-Doo themed Mystery Machine. Other facts about the parade include:

- The Parade was held inside of Grant Field from its inception until the mid-1940s.

- The Wreck Parade has occurred every year since 1932 with the exception of 1942 and 1943 due to gas shortages during World War II.

- The classic cars are featured first in the Wreck Parade, and they have to be at least twenty-five years old.

- The themed cars are second to come in the parade. They are sponsored by different groups and are fixed bodies that have only been altered cosmetically.

- Finally, the contraption vehicles are the last to be presented. These are student fabricated and are judged based on creativity and effective operation.

Apex Pedalers: The Mini 500's Tradition of Competition

Past Mini 500 champions reveal their winning strategies for one of Tech’s best homecoming traditions.By: Shelley Wunder-Smith

George P. Burdell. “The Horse.” RAT caps. The Institute abounds with storied student traditions. Arguably, however, none exemplify the spirit of Georgia Tech as much as the Mini 500.

“Practically speaking, it’s a team-based, multi-lap tricycle race,” says Ajay Mathur, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student and this year’s Mini 500 co-chair. “But in spirit, it’s the most ‘Techie’ tradition—involving engineering problems and requiring ingenuity and creativity.”

But First, A Little Background Info

On the Friday night before Homecoming, you will find hundreds of spectators lined up around Peters Parking Deck, near the heart of Tech’s campus, to watch a spectacle unlike any other. The Mini 500 began in 1969 as a circuit around then-Peters Park, as a nod to a fraternity prank during the sixties that had freshman pledges traversing campus on tricycles.

The Wreck—Tech’s 1930 Ford Model A Coupe mascot—sits at the starting line by the Chi Phi house on Fowler Street; behind it are 50 or so tricycles with students perched over them like huge birds. Most sit sideways, with one leg sprawled out to push themselves along.

The Mini 500 commences when the Wreck begins moving, and the riders launch their trikes forward, jostling the other racers like bumper cars in an effort to get past the Wreck and out in front.

Naturally, both the race logistics and the rules have evolved over the years. For a time, men were required to take 15 laps around the racecourse, while women finished 10. Now teams have four riders who switch out after two laps each, completing a total of eight; additionally, the front wheel must be reversed by the team’s three-person pit crew after every second lap, for a sum of three pit stops. A lap is around 0.4 miles, making for a race distance of about 3.2 miles.

Modification and Competition

The Ramblin’ Reck Club has overseen the Mini 500 since its beginning and now publishes the rule book online. The rule book describes what is and is not acceptable in terms of both racing behaviors and modifications to the tricycle—and there’s a good bit of creative leeway. One point, however, gets emphasized explicitly and repeatedly: “RED TRICYCLES WILL NOT RACE.”

Every year, the Reck Club purchases the tricycles directly from Radio Flyer, which come in their classic red color; accordingly, the Mini 500 rule book states that the one required modification is painting the tricycles (THWg!). Pictures of early Mini 500s show the tricycles were not modified much, if at all. These days, teams take the race quite seriously as both an athletic and an engineering challenge. Modifications have become increasingly sophisticated. “Build a Trike and Make UGA Pay for It” is a recent team that has been a repeat Overall Mini 500 Winner (2018, 2019, 2021, 2nd place 2022); they set a new course record in 2018, completing their race in 15 minutes, 9 seconds. PhD student Jacob Blevins, ME 20, MS ME 21, helped lead the team to victory. “I like the competition of it,” he explains. “You might think, oh, it’s a little tricycle race, but there are hundreds of spectators, hundreds of competitors, it’s broadcast live, and when you put a lot of effort into something that’s a big challenge and come out on top, it’s really satisfying.”

Team Build a Trike raced “casually a few times,” Blevins notes, before bicycling enthusiast and fellow mechanical engineering student Kuttler Smith, ME 17, MS ME 18, decided they should buckle down and get serious.

“And then from year to year, we updated our trike’s design based on issues from the previous year,” says Blevins. “For example, the tires are incredibly important, as is the seat length, and the handlebar shape, grip, and position, so you’re in an optimal position to push with your legs. We have try-outs every year for our riders—the race is really strenuous, so we look for people who are light and athletic.”

Blevins stops there. “I’m not allowed to disclose everything, because we have our secret formulas,” he adds, laughing.

Finding a Loophole

“Build a Trike was so athletic; we were looking for an edge to make us faster. We were literally trying to engineer a better option. What’s the most efficient way of moving this tricycle? How do we achieve that within the rules?”

That’s Iain MacKeith, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student, describing his Invention Studio team’s approach in the lead-up to last year’s Mini 500. They carefully analyzed the rules, pinpointing several ambiguities concerning allowed modifications. MacKeith brought bike-building experience to the team’s trike redesign: They disassembled the entire frame and rebuilt it, bringing the back two wheels so closely together on an axle, they essentially functioned as a single rear wheel. With a few additional modifications, this enabled Invention Studio’s racers to ride the trike like a conventional bicycle.

Notably, during the race the team was heavily booed by the watching crowd, who clearly felt that their tricycle’s alterations violated the spirit of fair play. A Reck Club referee even attempted to disqualify them for illegal modifications. Despite intense opposition, the Invention Studio team won.

“I think what we brought to the competition was the Georgia Tech engineering spirit: Here’s a design problem. How can we solve it and achieve the best result?” says MacKeith. His teammate, second-year mechanical engineering student Hilmy Rukmana, agrees. “We flopped a few times along the way, but that’s all part of the engineering process: trying, testing, failing.”

The Invention Studio team, it was ruled, won legally. They legitimately interpreted the rules as written and engineered their tricycle accordingly. In other words, they designed to win. In an email from Mathur and his co-chair, Aastha Singh, a second-year mechanical engineering student, the Reck Club commended the Invention Studio team on their “incredible creativity and success” but stated that going forward, “we will require the two back wheels of the tricycle to be at least 12 inches apart from each other.”

The Spirit of Georgia Tech

“Is there anything more Georgia Tech than the Mini 500?” Blevins asks. “It shows the high-achieving nature of Tech students who use their skills—designing, engineering, fabricating, building—for something silly, competitive, and fun.”

Singh says, “The Mini 500 is an exciting event that truly exemplifies the Tech spirit. It brings together many different groups that may not normally interact: participants from a wide variety of student organizations, facilitators from Reck Club, spectators from every sphere of campus, all to celebrate creativity, adaptability, and collaboration—really, everything that makes Tech so special to everyone here.”

“This is for the entire Yellow Jacket family,” she adds. “Students, parents, and alumni—we want everyone to come out and enjoy the Mini 500.”

Odd Tales From Homecoming

By: Jennifer Herseim

With a tricycle and a parade of Wrecks, Georgia Tech has always done Homecoming a little differently than other schools. Even stranger than Tech's Homecoming traditions themselves are the delightfully odd tales that have spun out of these festivities.

James “Taxi” Smith

Odd stories are almost baked into the freshman cake race, an annual competition where winners receive a homemade cake made by Tech faculty and students. The cake race has been part of Homecoming traditions since 1935, but it started at Tech in 1911. One bizarre tale stemming from this than other schools. Even stranger than longstanding Tech tradition involves a clever 16-year-old freshman named James Warren Smith, Cls 1923.

Smith was lagging behind other runners in the 1922 cake race when he spotted a taxi-cab. He hailed the taxi and asked the driver to take him part of the way through the course, thinking no one would find out. But, when he jumped out of the car just before the finish line, the other runners were there welcoming him with the nickname “Taxi” Smith. The name stuck with him for the rest of his life, even as mayor of Albany, Ga., from 1954 to 1955. He died in January 2000, still known as “Taxi.”

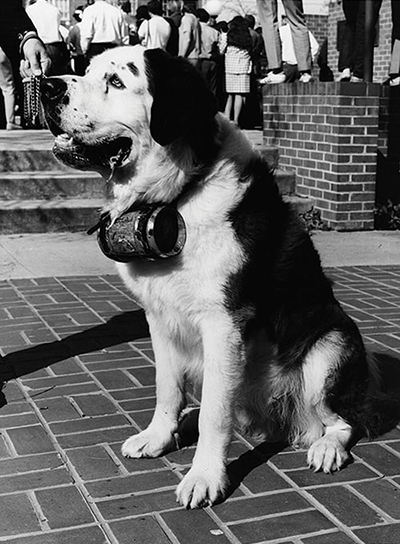

Meet Chai, Tech’s First Homecoming Dog

Meet Chai, Tech’s First Homecoming Dog

Tech has Mr. and Ms. Georgia Tech, but here’s a tail of Tech’s first Homecoming Dog. In 1971, Chai, the original St. Bernard mascot of fraternity Lambda Chi, won Tech’s first Homecoming dog show.

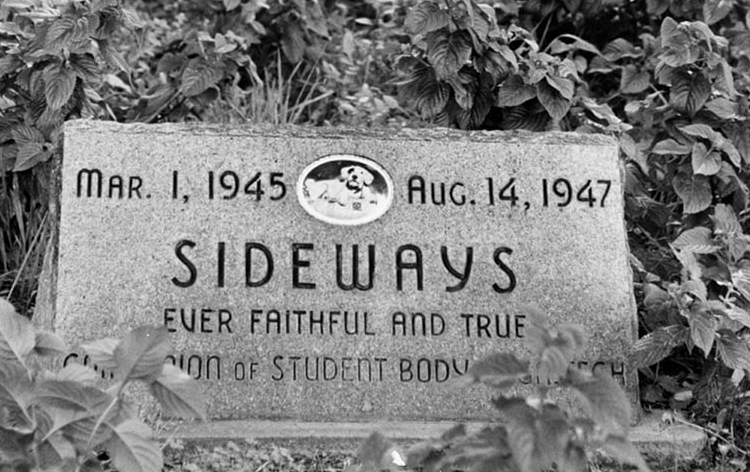

Chai’s trophy was inscribed with the name of one of Tech’s most famous four-legged friends, Sideways, a white terrier who showed up on campus in 1945. Sideways, who earned his name because of the way he walked after sustaining an injury, quickly became a popular figure on campus, attending classes and even leading Tech’s football team onto the field.

This marble monument to Sideways is northwest of Tech Tower. It is inscribed "Ever faithful and true companion of Student Body of Ga. Tech."