A New Trajectory

By: Jennifer Herseim | Categories: Alumni Achievements

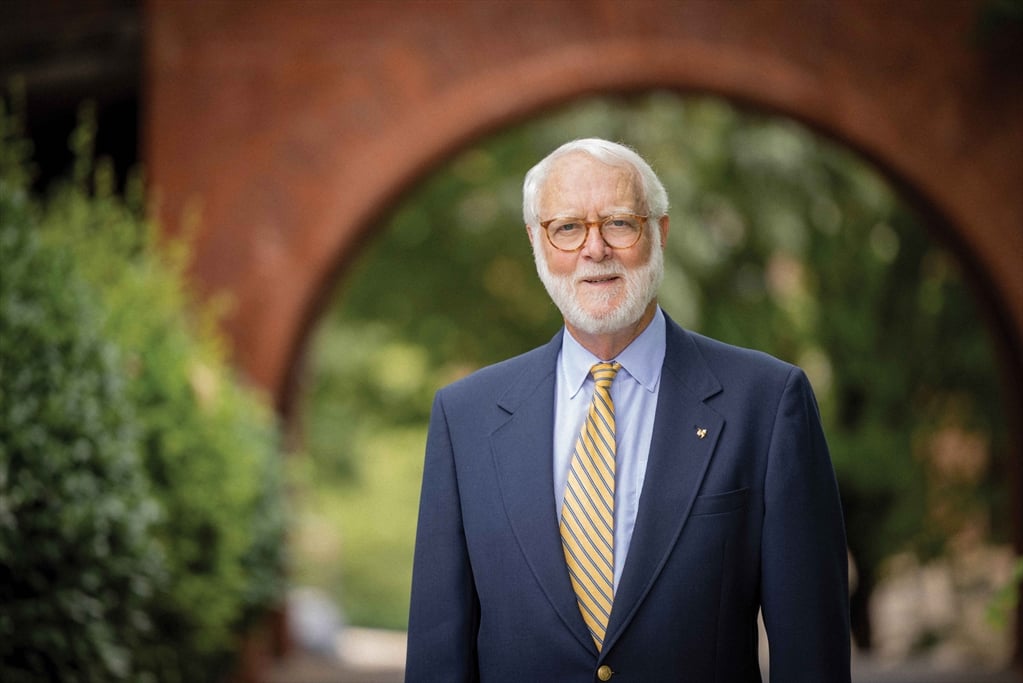

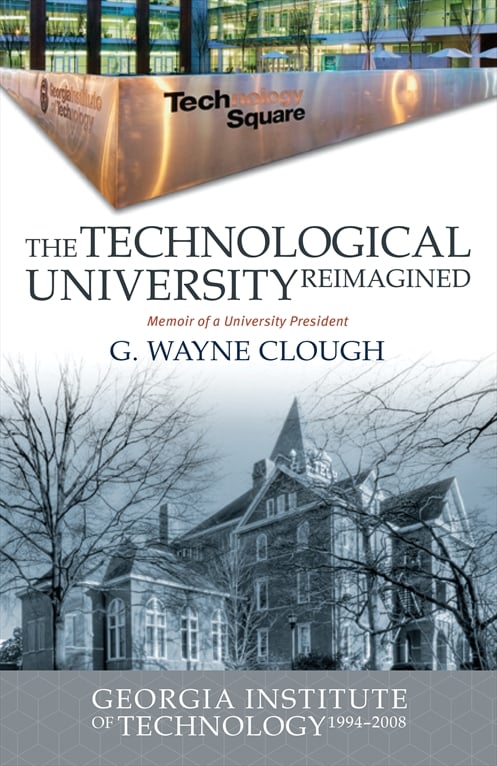

These moments—and the choices that led to them—are what Dr. G. Wayne Clough, Georgia Tech’s 10th president and the first alumnus-president in Institute history, lays out in his recent book, The Technological University Reimagined.

Clough, CE 63, MS CE 65, HON PhD 15, took office in 1994 with millions of dollars of promised construction projects looming ahead of the Olympics, which was just two years away. His legacy could have been tied to these challenges, but instead, he held fast to the belief that Tech was poised for a greater change.

But first, he had to survive those initial trials. Clough faced situations that he never imagined he might face in higher education, like how to remove “weapons-grade” uranium from the middle of a college campus ahead of the world’s biggest athletic event.

“A lot happened during this time in Georgia Tech’s history that was not documented,” Clough says. “I decided to help fill part of the gap by writing this book.”

Royalties from the book support the G. Wayne Clough Georgia Tech Promise Program, a fund that Clough created during his presidency to make Tech more affordable for low-income students.

Q: Why was writing this important to you?

Q: Why was writing this important to you?I’ve always loved history. My last office was at the Smithsonian, and I was amazed at how they venerate history and what documenting it means for understanding an institution’s trajectory. The last official history of Georgia Tech was published in 1985 for its centennial. I talked to the author of that book and we both agreed that something needed to be done. I wasn’t going to write the history from 1985 to 2021, but the part that I could write about was the 14 years when I was president.

Q: At the start of your tenure, you had ambitious goals, but also a series of immediate problems. How did you keep focused while putting out the fires?

When I came in, we were considered a regional university at the time. We weren’t in the top 50. The College of Engineering was not in the top 10. But we had the capacity, and we were poised to create a different trajectory for Tech. I told the team, put all the issues and the Olympics aside, we’re thinking about the future of Georgia Tech. When we finish the Olympics, we’re not going to be sitting around thinking what to do next; we’re going to launch.

I hired people like Bob Thompson, who was at the University of Washington, who became our executive vice president of administration and finance, and Jean-Lou Chameau, who was incredibly bright, and who could take on new research initiatives.

Having the right staff in place in time for the Olympics was important. There was no saying, so what if we’re six weeks late? We had to be ready. Fortunately, we had the “two Bills” as I called them (Retired Gen. Bill Ray and Retired Col. Bill Miller,) who were thoughtful, ex-military types who got the job done.

Q: One surprise leading up to the Olympics that you write about was the belated discovery by the federal security team that Tech had a nuclear reactor on campus. That sure is an unusual situation to deal with as president.

They put the reactor in just before I was a student at Tech in the ’60s. It looked like a reactor, so how could they have missed it? The other weird thing was it wasn’t licensed because it had outlived its purpose, and to decommission a reactor, it needs to be licensed. Well the people against nuclear power didn’t like me trying to relicense it. I felt like a fly caught in sticky paper. No matter where I tried to move, there was no way out. We worked with Gary McConnell, director of the Georgia Emergency Management Agency, who helped us get in contact with Washington and eventually Vice President Al Gore. Finally, we got the fuel rods out before the Olympics. Of course, during the Olympics, I was forced to go a different route to campus through Fifth Street and that’s when I saw the for-sale signs in Midtown that led to the idea for Technology Square.

Q: In the book, you describe several defining moments during your presidency. What were some of those moments?

I had this insight into bioengineering from my time at Virginia Tech and the University of Washington. I said here’s the place where engineering doesn’t sneak in but jumps into medicine. So, when Bob Nerem came and he said, “Could you help us build an addition to one of the oldest buildings on campus?” I said, “No. Your plans and my plans are much bigger than that.” We ended up building a whole sequence of buildings in the molecular science quadrant. It was a question of getting people to lift their sights. And luck. The luck part was that Mike Johns had just come to Emory as the head of Emory Healthcare and the medical school. [Johns and Nerem had an impromptu meeting on an escalator that sparked the idea for the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering.]

Another moment was when we were selected as finalists by the National Science Foundation for an engineering research center. We hosted the committee for breakfast and joining us was Bill Todd, who was an alumnus and president of the Georgia Research Alliance. When they pressed us on cost-sharing, Bill stood up and said, ‘If you will, I will.’ That was a key moment to have him pledge to help us meet the requirements.

Q: You describe in the book working to create a new culture around undergraduate experiences at Tech. Did you feel well-suited for this because you went through it yourself?

I understood first-hand what the “proving ground” at Tech felt like. When I came back to Tech, the freshman class had the highest test scores for a public university in the nation, but our graduation rate, 66%, was the lowest among our peers. The reason for the low rate was not challenging academics because the majority of students leaving were in good standing. It wasn’t a question of making Tech “easier,” but about creating an educational experience that provided opportunities for students to grow and to live and study in facilities that supported their needs. Adding options like study abroad, independent research, music and poetry created a vibrant learning environment. It demonstrates that this isn’t just about our intellect, but about our heart. Proof is that the graduation rate today is over 90%. I am proud to have a hand in making this happen.