Exploring Deep Space

By: Jennifer Herseim | Categories: Alumni Interest

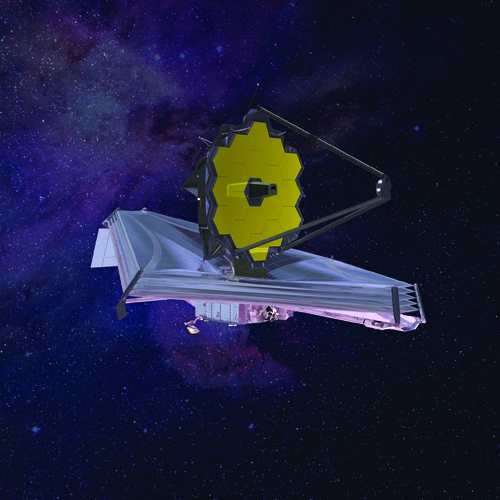

In just three years, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has transformed astronomy. It’s provided evidence that the universe might be expanding more slowly than previously thought, revealed Earth-like extrasolar planets, and captured the distant light of the earliest galaxies. “One of the most fascinating questions that it might help answer is, can we detect life on other planets?” says David Ballantyne, a physics professor at Tech who studies supermassive black holes.

“JWST is hard to compare to Hubble or other previous telescopes because it’s so sensitive to very distant and dim sources. It’s optimized to detect infrared light, which allows us to detect the warm glow from planets around other stars or faraway galaxies whose light has been stretched by the expanding universe,” Ballantyne says.

Several Yellow Jackets helped prepare JWST for launch. Robby Estep, AE 97, was the instrument manager for the Micro-Shutter Subsystem. These small windows with shutters about the size of a few human hairs, were developed for JWST’s Near Infrared Spectrograph.

Len Seals, MS EE 99, MS Phys 00, PhD Phys 01, the associate branch head of the Optics Branch at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, worked on the telescope’s Integrated Science Instrument Module. He supported optical analysis that allowed for the optimal alignment of the instruments. Later, he worked as a straylight analyst, building straylight models for several of JWST’s instruments. When he joined the project, it was facing cancellation because of delays and budget overruns. On top of that, Hurricane Harvey flooded their test facility in Houston in 2017. “With the dedication of the project and NASA we were able to complete the integration of instruments largely on time,” he says.

Len Seals, MS EE 99, MS Phys 00, PhD Phys 01, the associate branch head of the Optics Branch at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, worked on the telescope’s Integrated Science Instrument Module. He supported optical analysis that allowed for the optimal alignment of the instruments. Later, he worked as a straylight analyst, building straylight models for several of JWST’s instruments. When he joined the project, it was facing cancellation because of delays and budget overruns. On top of that, Hurricane Harvey flooded their test facility in Houston in 2017. “With the dedication of the project and NASA we were able to complete the integration of instruments largely on time,” he says.

Before the telescope could launch, Jesse Leitner, MS AE 92, PhD AE 95, was part of the final risk assessment. He and the chief engineer at Goddard described the challenges of testing JWST’s readiness in a 2022 article for Aerospace America, including deploying a tennis-court-sized sundshade under extreme conditions. In the end, they signed off that the telescope was ready for its launch in December 2021.

Studying Cosmic Mysteries

JWST’s early findings could provide clues to a number of astrophysics questions. “For the last 25 years, we’ve had a cosmological model dominated by dark matter and dark energy yet, we don’t know what those are,” says Ballantyne. “Recent data from JWST suggests that the universe is not expanding as quickly as we once thought. There could be something deeper at play that we don’t really understand. Perhaps the universe isn’t destined to expand forever.”

Those questions interest Kate Napier, Phys 17 (pictured right), who is part of the Observing Specialist Team at the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile. The observatory features the largest digital camera (3.2 billion pixels) ever built. For the next 10 years, it will capture the entire Southern Hemisphere sky every three to four nights. “It’s essentially building a time lapse video of the night sky. The first year of the survey is expected to surpass the total data gathered by all previous optical observatories combined,” Napier says. “One of the main goals is to shed more light on the nature of dark matter and dark energy.”

Those questions interest Kate Napier, Phys 17 (pictured right), who is part of the Observing Specialist Team at the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile. The observatory features the largest digital camera (3.2 billion pixels) ever built. For the next 10 years, it will capture the entire Southern Hemisphere sky every three to four nights. “It’s essentially building a time lapse video of the night sky. The first year of the survey is expected to surpass the total data gathered by all previous optical observatories combined,” Napier says. “One of the main goals is to shed more light on the nature of dark matter and dark energy.”

For her postdoctoral research, Napier will use the Rubin data to study the current expansion rate of the universe. She’s using an independent measurement method that relies on quasars—the bright cores of some galaxies that are powered by supermassive black holes—whose light has been bent by galaxy clusters, which act like a cosmic telescope, magnifying objects farther away, Napier says.

Working at the observatory is personal to Napier, who advocated for it to be named after Vera C. Rubin, an American astronomer who provided the first compelling evidence of dark matter. It’s the first national observatory that the U.S. has named after a woman.

“Georgia Tech gave me the opportunity to be mentored by a lot of women in science,” says Napier, who served as president of the Society of Women in Physics while at Tech. “My leadership skills flourished because of the opportunities I was part of at Georgia Tech.”

Yellow Jackets Contributing to Deep Space Missions

- Robby Estep, AE 97, was the instrument manager for the Micro-Shutter Subsystem.

- Jesse Leitner, MS AE 92, PhD AE 95, was part of the final risk assessment for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

- Len Seals, MS EE 99, MS Phys 00, PhD Phys 01, the associate branch head of the Optics Branch at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, worked on JWST's Integrated Science Instrument Module.

- Kate Napier, Phys 17, is part of the Observing Specialist Team at the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile.

-

Gregory Dubos, MS AE 07, PhD AE 11, is Europa Clipper flight director and Spacecraft Systems lead.

-

Tessa Rogers, MS AE 23, was a systems engineer at Northrop Grumman who worked on JWST. She’s now a mechanical engineer at Lockheed Martin.

-

Nathan P. Brown, AE 16, MS AE 18, PhD AE 21, was a co-op student who worked as a structural and thermal engineer on the James Webb and Space Launch System with ATA Engineering, Inc.

-

James Kenyon, AE 96, is the director of NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. Glenn is one of NASA’s cutting-edge research centers, contributing to the agency’s missions and major programs, including advanced technology in power, propulsion, and communications, which are critical for deep space research.

Top Image: The central region of the Chamaeleon I dark molecular cloud captured by the James Webb Space Telescope’s Near-Infrared Camera. (Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA; Science: IceAge ERS Team, Fengwu Sun (Steward Observatory), Zak Smith (The Open University); Image Processing: Mahdi Zamani (ESA/Webb))

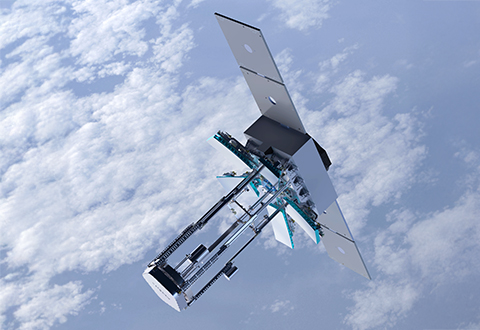

Top Photo: Rendering of Webb’s Sunshield and hexagonal mirrors deployed in space. (Credit: NASA, ESA, and Northrop Gunmman) Photo of Kate Napier, Phys 17, provided by Napier.