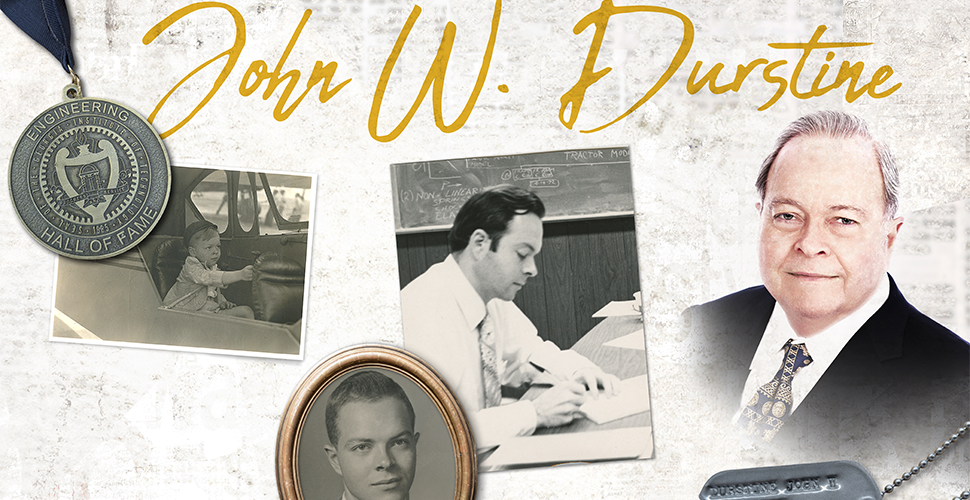

John W. Durstine

By: Kelley Freund, Archival Material Courtesy of Georgia Tech Archives | Categories: Featured Stories

A few months after John Warren Durstine, ME 57, passed away in February, Georgia Tech President Ángel Cabrera received word that Durstine had left his entire estate to the Institute. When told those assets added up to $100 million, Cabrera said he nearly fell off his chair.

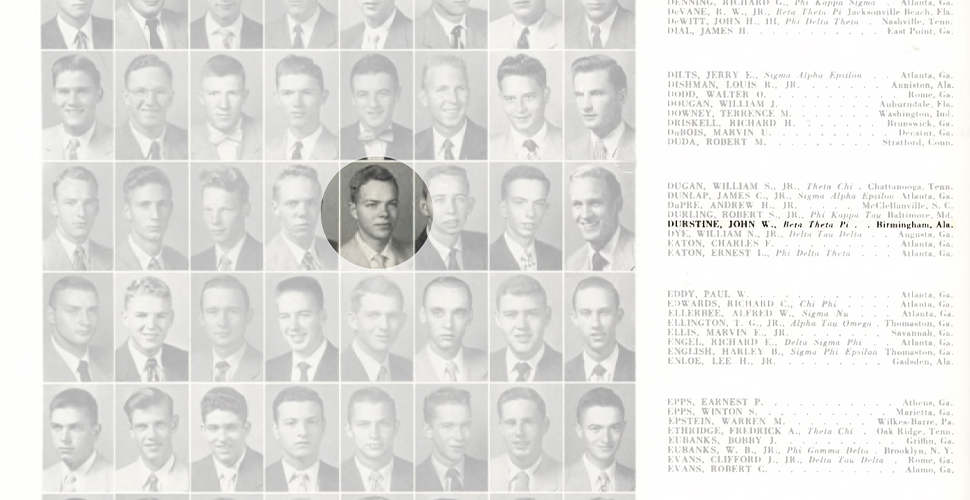

Cabrera had never heard of Durstine. In fact, it seems few people have. Those who did know him say he was mild mannered and bright, and that he loved Georgia Tech. But even to those who met him, Durstine was a bit of a phantom. During his time at Tech, he seems to have only been in one photo in the school’s yearbook. He never married and had no children, and no obituary was written for him. Even his exact role with Ford Motor Company, where he spent 32 years, was not clear.

So who is this man who left the Institute its largest single gift in history?

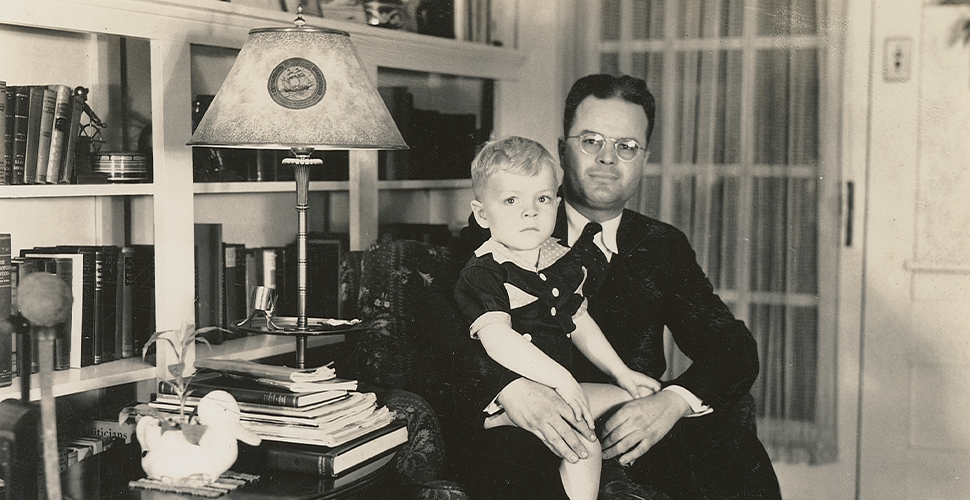

Durstine became an engineer like his father, John Elliot Durstine.

Durstine became an engineer like his father, John Elliot Durstine.

Durstine was a native of Birmingham, Alabama. He had a sister, Joan, who was four years younger to the day. According to notes written by Ann Dibble, a former director of gift planning at Tech, Durstine liked to build things and began creating birdhouses out of apple crates when he was 6 years old. He probably took after his father, who was an engineer and fluent with transmitter radios. At least once, his father used his radio to transmit to Australia using the Kennelly-Heaviside layer in the earth’s ionosphere, causing the lights in his neighborhood to flicker.

The Durstine family (L-R): Durstine, his younger sister, Joan, his father, John E., and his mother, Reba Marie (Towle).

The Durstine family (L-R): Durstine, his younger sister, Joan, his father, John E., and his mother, Reba Marie (Towle).

The Durstine household must have been one that stressed the importance of education. Durstine headed to Georgia Tech and went on to receive an MBA from Harvard. According to Dibble’s notes, in high school he wanted to be a surgeon and started out as a physics major at Georgia Tech before switching to mechanical engineering. Joan attended Duke University and later earned her PhD from Indiana University.

Wayne Waddell, EE 56, was a classmate of Durstine’s at Tech; the two met while pledging Beta Theta Pi.

“I don’t know how or when it happened, but I remember John telling me he had had a serious accident,” says Waddell. “After that, he became dedicated to exercise and rebuilding his body, and he lived on a strict schedule. Nothing interrupted it.”

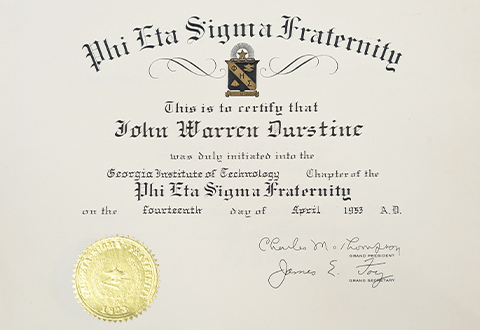

In fact, Durstine made the Dean’s list three years in a row while at Tech and was elected in 1953 to the national freshman honorary fraternity, Phi Eta Sigma. He was a member of the honors engineering fraternity Tau Beta Pi and graduated from Tech with honors.

In fact, Durstine made the Dean’s list three years in a row while at Tech and was elected in 1953 to the national freshman honorary fraternity, Phi Eta Sigma. He was a member of the honors engineering fraternity Tau Beta Pi and graduated from Tech with honors.

Waddell says Durstine lived in a dormitory all four years at Tech but came to the fraternity house for meals. One year, Durstine’s dormitory floor housed several football players who decided to play a practical joke and mess with Durstine’s strict schedule. Somehow, they set Durstine’s clock back a few hours. When his alarm went off, he got up and began his usual preparation for the day. The football players even showed up in the common bath area, some shaving and others showering so that Durstine wouldn’t catch on. It was winter, so it was still dark in the mornings, and Durstine was none the wiser as he set out to the Beta house for breakfast. There, instead of his meal, he discovered a group of architecture students pulling an all-nighter around the dining room table. Waddell remembers that Durstine took the joke well.

In January 1957, the Georgia State Examining Boards issued an Engineer-In-Training certificate indicating Durstine had passed his Professional Engineering exam. After graduating third in his class from Tech, Durstine served in the U.S. Air Force. He joined because he wanted to fly planes, but there was a change to service contracts during his time serving, and he would not meet the years of active duty required to fly. (Top Gun would become his favorite movie.) Later, when reflecting on his years in the Air Force, Durstine remembered the intense cold, white-outs, and seeing the Northern Lights during his first station in Goose Bay, Labrador. He was eventually transferred to Palm Beach, Florida. Later as the base was closing down and units were pulling out, Durstine ended up as the only officer on base with a small group of enlisted men. He wrote to Waddell, “I must be the only first lieutenant base commander in the Air Force.”

In January 1957, the Georgia State Examining Boards issued an Engineer-In-Training certificate indicating Durstine had passed his Professional Engineering exam. After graduating third in his class from Tech, Durstine served in the U.S. Air Force. He joined because he wanted to fly planes, but there was a change to service contracts during his time serving, and he would not meet the years of active duty required to fly. (Top Gun would become his favorite movie.) Later, when reflecting on his years in the Air Force, Durstine remembered the intense cold, white-outs, and seeing the Northern Lights during his first station in Goose Bay, Labrador. He was eventually transferred to Palm Beach, Florida. Later as the base was closing down and units were pulling out, Durstine ended up as the only officer on base with a small group of enlisted men. He wrote to Waddell, “I must be the only first lieutenant base commander in the Air Force.”

He earned his MBA from Harvard Business School in 1962 and took a job with Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he spent more than three decades. During his time with Ford, he helped shape truck and light vehicle design, powertrain strategy, and advanced systems engineering. He authored a technical report on the truck steering system that won the L. Ray Buckendale Lecture Series award in 1973. His first donation to Georgia Tech was a $100 gift to Roll Call, the Institute’s annual fund, in 1978, and his philanthropy continued over the next decades. Ward Winer, who served as chair of Tech’s George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, recognized Durstine’s success in the automotive industry and potential for continued philanthropy. When Winer retired in 2008, he told his successor, William Wepfer, “Keep on eye on John Durstine. There’s something there.”

Wepfer, along with Dibble, began visiting Durstine in Michigan, most of the time meeting him for lunch at Durstine’s favorite Italian restaurant, Andiamo. Wepfer says Durstine would bring a satchel that contained a manila folder, which was all of his estate planning. At some point, he had become very good at investing, apparently doing most of his own research—at his home, there were shelves of company prospectus documents with underlined passages.

“Comparing anyone to Warren Buffet is absurd, but I think there was a little bit of Warren Buffet in him,” Wepfer says. “He had a very analytical mind and a good sense of how the world works. I think he was a master day trader before day trading got a bad name.”

At lunch, Wepfer says Durstine probed him about the mechanical engineering school and the kinds of things they were working on. Wepfer says that in retrospect, Durstine was using those meetings to get feedback to create his estate plan.

But Georgia Tech wasn’t the only topic discussed during these meetings. Durstine hated small talk, but he liked to brag about his sister, Joan, and her work in the Dallas art scene. Wepfer and Dibble discovered that Durstine was a lifetime learner. During his time with Ford, he learned Japanese for his twice-a-year trips to Japan. Later, he took classes at a technical college to learn to wire houses for sound, security, and computer systems. (Durstine noted in a letter that these technologies didn’t exist when he left Georgia Tech.) He was also interested in genealogy, researching the Durstine family history and attending a reunion in 1992 in Pennsylvania. He kept meticulous records and notes from his trip from Detroit to the reunion.

Durstine at the Georgia Tech College of Engineering Hall of Fame ceremony in 2014.

Durstine at the Georgia Tech College of Engineering Hall of Fame ceremony in 2014.

One time, Wepfer took Durstine to a motorsports competition held at Michigan International Speedway and hosted by the Society of Automotive Engineers. Durstine spent the day with Tech’s team.

“It was magic,” says Wepfer. “He interacted with the students and asked them good, tough questions. There were two times I saw the man incredibly happy. That was one of them.”

The other was when Durstine was inducted into the College of Engineering Hall of Fame in 2014. “He loved it,” Wepfer says. “He was grinning from ear to ear.”

In 2010, Durstine had told Wepfer and Dibble that the estimated value of his estate was $10 million. The two were instructed not to reveal the amount to anyone, and they kept that promise for fear of Durstine going back on his word. Wepfer believed that the $10 million estimate was conservative. But no one expected the $100 million that came Tech’s way in February.

Durstine left instructions that the funds should be used to recruit and support faculty for the Woodruff School; it was clear he had been paying attention during all those lunch meetings with Wepfer. When Wepfer became chair of the Woodruff School in 2008, mechanical engineering programs across the country were experiencing a surge in popularity and enrollment, and Wepfer was trying to recruit more faculty. It was difficult to recruit senior professors without having an endowed chair, and he says even now, universities need to have discretionary money for junior faculty to support graduate students, do work in a laboratory, or travel. Durstine’s gift will establish endowed chairs, professorships, and faculty awards. This will help Georgia Tech recruit, develop, and retain world-class professors, ensuring that the Institute will continue to be a place that sets students up to lead successful lives, just as it was for Durstine.

Cabrera says that he wishes he could’ve met Durstine so he could ask him a million questions. But as we know, Durstine wasn’t one for small talk.

“Perhaps that’s why he arranged things the way he did,” Cabrera says. “He wanted the gift to do all the talking—to send us a simple yet powerful message: Make Georgia Tech stronger and continue to transform the lives of generations of talented students so they can do great things. And that’s the best way for us to thank him—to make sure we do just that.”

Special thanks to the Georgia Tech Library and Georgia Tech Archives for providing materials from the John Durstine Personal Collection.