Of the three individuals affiliated with Georgia Tech at the 1996 Olympics, all three received gold medals.

Jack Purdy, BA 22

Of Tech's 41 athletes and coaches who have participated in an Olympics, three represented the U.S. at the 1996 Games: Bobby Cremins as assistant coach of the USA Men's Basketball team, and Derrick Adkins, ME 93 and Derek Mills, EE 95, who both represented the U.S. in Track & Field. All three took home gold medals.

Derrick Adkins, ME 93 and Derek Mills, EE 95: Georgia Tech's Golden Sprinters

Adkins won gold in the 400m hurdles and Mills in the 4x400m relay, making it the third time a Jacket had won the 4x400m relay (Antonio McKay, IM 87, won it in 1984 & 1988).

Adkins and Mills qualified for the Olympics at the U.S. Olympic Trial meet, which was conveniently held at Centennial Olympic Stadium in Atlanta. Between training at the Griffin Track at Tech and competing at the Olympic Trials and the Olympics themselves, the pair did all of their relevant running within a three-mile radius. Mills even lived on campus during the Olympic Games.

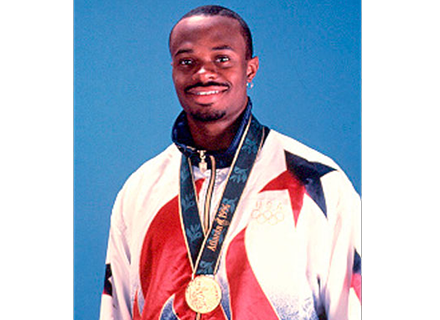

Mills (pictured left) handing off the baton during the 4x400m relay.

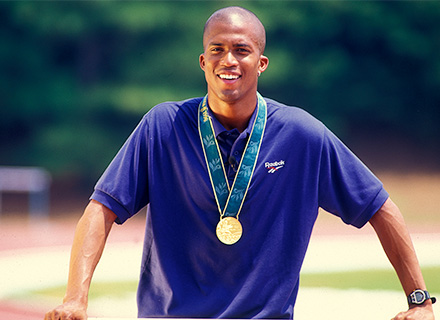

Adkins with his gold medal. "I keep it in my apartment. It's tucked away," Adkins says.

"The games, for those two-and-a-half weeks was a surreal experience, especially because I was able to run well. It was like a dream. And then for several weeks thereafter, I was invited to speak on the Today show, and a lot of media wanted to speak to me," says Adkins, who ran the 400m hurdles in 47.54 seconds.

The Today show’s studio in front of the Campanile.

The Today show’s studio in front of the Campanile.

Inside the Olympic Village, athletes had access to unlimited free McDonald’s with dishes from around the world. “It was pretty amazing. I think they put six or seven McDonald’s on campus,” remembers Mills.

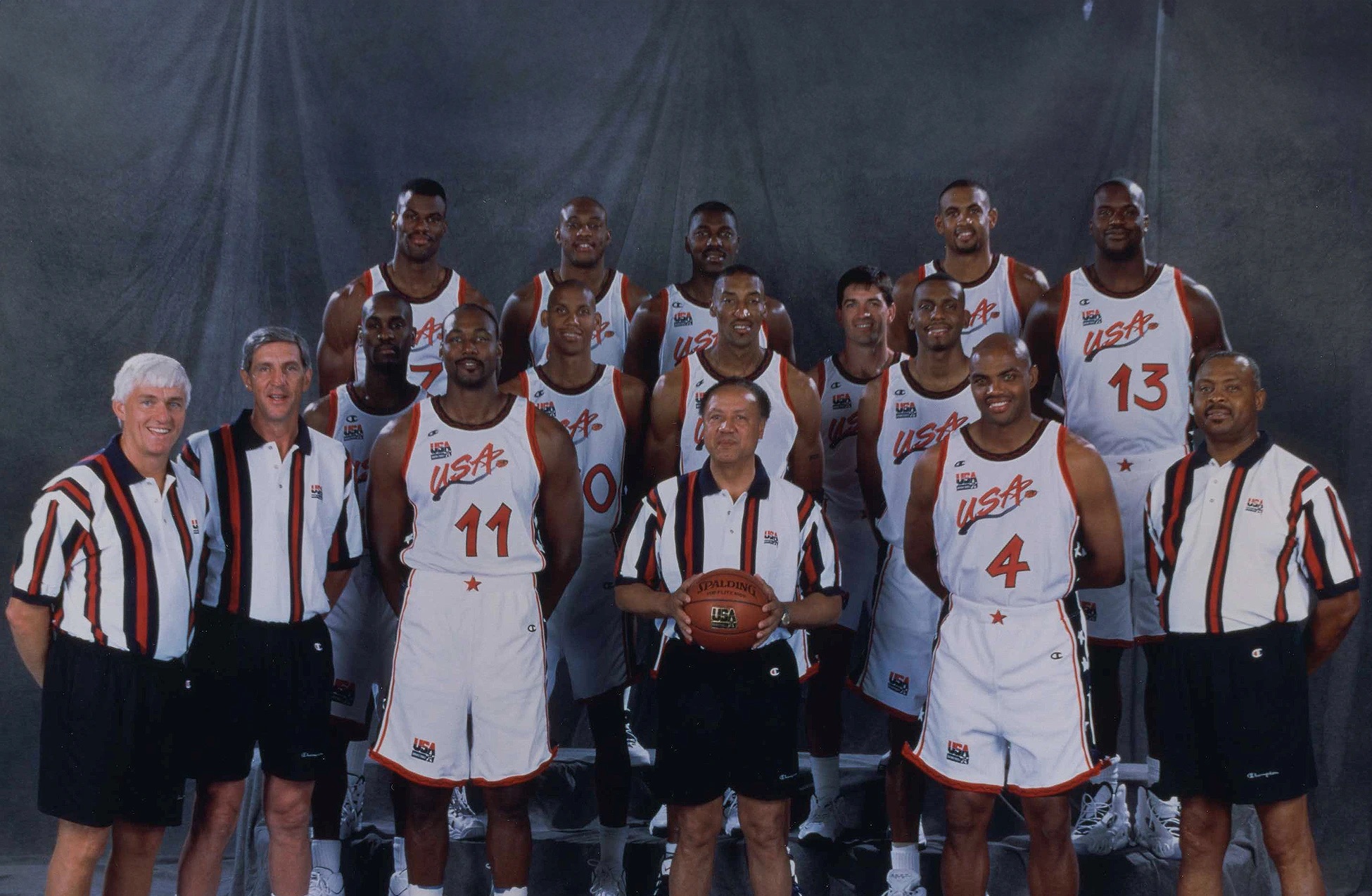

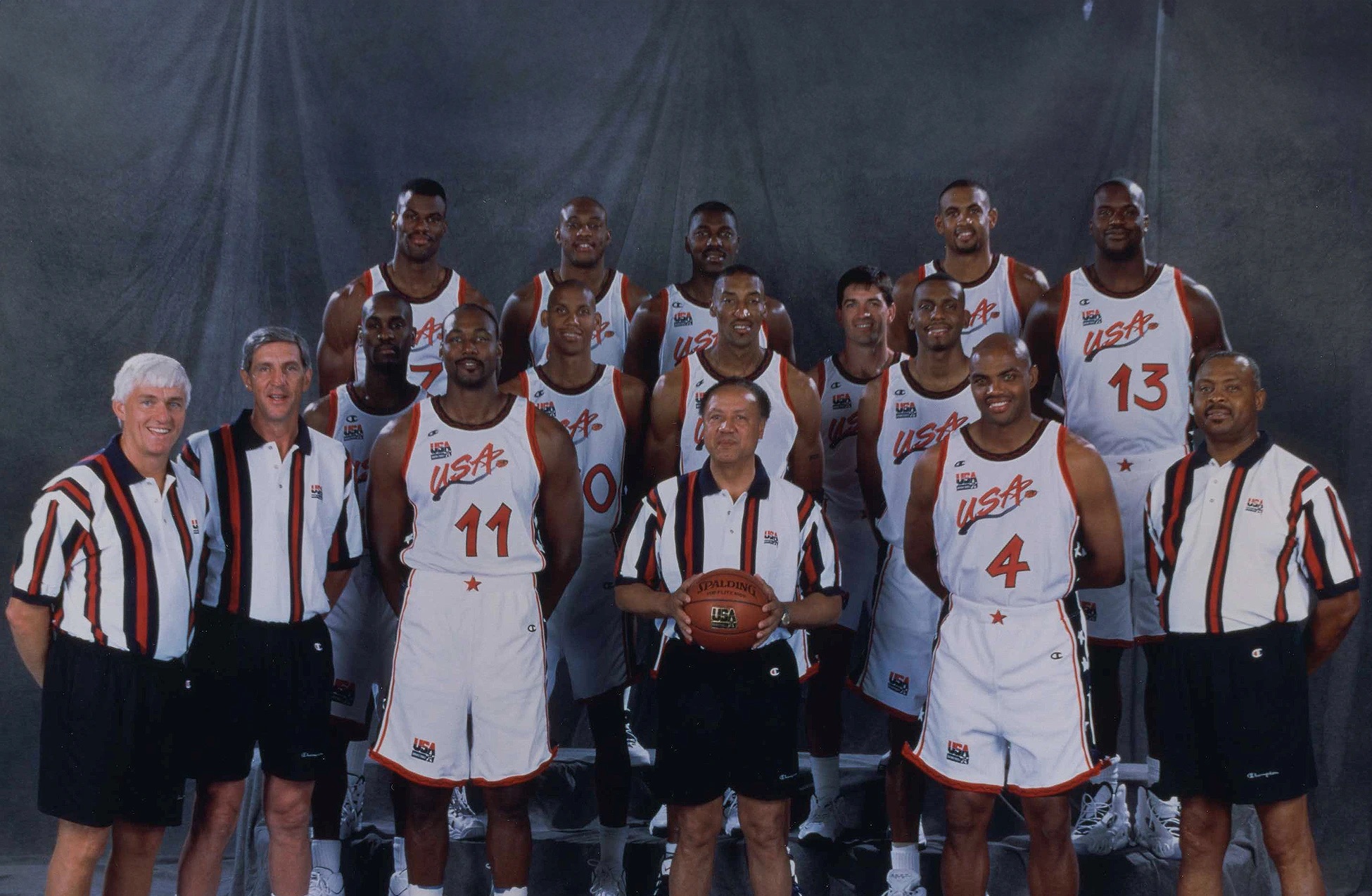

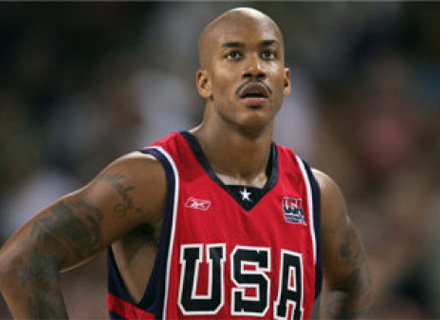

The 1996 U.S. Men's Basketball team. Bobby Cremins on the far left. Photo courtesy USA Basketball

The 1996 U.S. Men's Basketball team. Bobby Cremins on the far left. Photo courtesy USA Basketball

Coach Cremins' Olympic "Dream Team III"

Georgia Tech Basketball Coach Bobby Cremins reflects on serving as the assistant coach to the 1996 gold-medal U.S. Men's Basketball team.

By: Jack Purdy, BA 22

For the 1996 Olympics, the Team USA Men's Basketball coaching staff selected two prominent Atlanta basketball coaches: Lenny Wilkens from the Atlanta Hawks was named head coach and Georgia Tech's Bobby Cremins was selected as assistant coach. Cremins had just completed his 15th season as Tech's men's basketball coach.

Joined by assistant coaches Jerry Sloane and Clem Haskins, the coaching staff led one of the most dominant Olympic basketball teams ever built with 11 hall-of-famers.

Cremins with the U.S. Men's Basketball coaching staff during a game during the 1996 Olympics.

Cremins with the U.S. Men's Basketball coaching staff during a game during the 1996 Olympics.

Twenty years following the Olympics, Cremins was the 2016 recipient of the Honorary Alumnus designation from the Georgia Tech Alumni Association.

Q: When you return to campus, are there parts that give you flashbacks to the Olympics?

BC: When I see the Natatorium, I do think about it. They also did some nice renovations in the Alexander Memorial Coliseum (today, it's called the McCamish Pavilion). I was really pleased. It gave us a good upgrade. One of our biggest improvements was to the dorms. We fought for a few rooms, and those helped with our recruiting.

Q: How did you become an assistant coach for Team USA?

BC: What made it possible was my prior involvement with Team USA as a player and coach. I tried out for the 1972 Olympics. I was an assistant coach with Lute Olson at the 1986 Fédération Internationale de Basketball (FIBA) World Cup, which we won. Then, we qualified for the Olympics while I was head coach of the world qualifying team. When they called me, I was really surprised. It was such a great honor. I had to check with my boss, Dr. Homer Rice (then Georgia Tech's Director of Athletics), and my wife because it was such a long commitment.

Q: How did you split your time between coaching Georgia Tech and Team USA?

BC: Team USA didn't get together until three weeks before [the Games]. I stayed at my office at Georgia Tech until Coach Wilkens had a pre-meet in Chicago with the staff. That's when I shut down my Georgia Tech work. I turned it over to my assistant coach, Kevin Cantwell. I checked in every other day and, if there were any problems, they could call me. I wanted to give Coach Wilkens all I had.

Q: From a strategic perspective, how did you, Wilkens, and Sloane manage games knowing you were heavy favorites?

BC: We did not run a lot of set plays. Wilkens would say, "get it inside," "penetrate more." He let the players play as long as they didn't lose sight of what our goal was. Our mission was simply to win the gold medal and not to screw it up. We had to go through a few rounds where we were heavy favorites, and then it got serious in the semifinals, but we took care of business there.

In the finals against Yugoslavia, things got hairy. At halftime, we were only up five points, and that shook everyone up. In the second half, it got down to the nitty gritty, and Coach Wilkens made a brilliant move. We took Shaquille O'Neal out because he was having trouble guarding the other bigger players. We put David Robinson in at center, Scottie Pippen at power forward, and played three guards: John Stockton, Reggie Miller, and Mitch Richmond. Their quickness turned around that game.

Lowe’s story began at Georgia Tech in 2002. She had come all the way from Riverside, Calif., to not only pursue a track career but also to challenge herself in the classroom. “Before students even get there, they’ve made the decision to come to Tech knowing the academics are going to be challenging while trying to compete at the NCAA Division I level,” says Alan Drosky, women’s track and field head coach for the Yellow Jackets. “A lot of young people have ambition to be excellent in everything. But Chaunte’s drive to actually reach her goals is not common at all.”

Lowe’s story began at Georgia Tech in 2002. She had come all the way from Riverside, Calif., to not only pursue a track career but also to challenge herself in the classroom. “Before students even get there, they’ve made the decision to come to Tech knowing the academics are going to be challenging while trying to compete at the NCAA Division I level,” says Alan Drosky, women’s track and field head coach for the Yellow Jackets. “A lot of young people have ambition to be excellent in everything. But Chaunte’s drive to actually reach her goals is not common at all.” Lowe doesn’t pretend that the diagnosis didn’t frighten her. But she says she reacted the only way she knew how—the way she had learned in college. She did her research, made a plan, put together the best team of doctors, and put herself in the best position to overcome the disease. After doing all that, making a fifth Olympics might not seem as impossible as it once had.

Lowe doesn’t pretend that the diagnosis didn’t frighten her. But she says she reacted the only way she knew how—the way she had learned in college. She did her research, made a plan, put together the best team of doctors, and put herself in the best position to overcome the disease. After doing all that, making a fifth Olympics might not seem as impossible as it once had.