Letters to the Editor: Stellar Co-op Experience, Dorothy Crosland, Control-Line Plane, Tech's Resident Glassblower

| Categories: Featured Stories

Stellar Co-Op Experience

It was with strong interest that I read the Fall 2025 GT Alumni Magazine, especially about projects in space and the Moon. I was a sophomore EE in December 1967 when I reported to IBM Huntsville to begin my co-op assignments working on the Saturn V rockets for the Apollo program. IBM had the contract with NASA to build the Instrument Unit, the “brains” of the Saturn V rockets. The Instrument Units provided navigation, guidance, telemetry, and mission control of each Saturn V rocket flight. I conducted hardware acceptance testing and software programming for flight verification and failure analysis of five Apollo missions including the Apollo 7, 8, 10, 11, and 13 missions. I remember seeing bulletin boards at the IBM Huntsville offices with a quote by Wernher von Braun, lead designer of the Saturn V. The quote was, “If the Saturn V is 99.9% reliable, there will be 5,600 defects.” It was an exciting and unforgettable experience and one of the reasons I treasure my time at Tech. Go Jackets! —Everett “Stony” Stonebraker, EE 71, of Coral Gables, Fla.

Faculty Impressions

In 1966, Tech Professor Alson H. Bailey was my Ordinary Differential Equations professor. He gave a strict appearance each morning as he entered the classroom after we all had been seated. His lectures were wonderful. As we conquered each new type of equation, he would say, “We have new challenges to face. A new type of equation that doesn’t yield results. But you are up to the challenge. Your thought processes have worked. You have succeeded.” And so, as the term progressed, we all felt that we could meet each new challenge. And near the end of the term, he actually smiled as if to say, “You met the challenge. Now go take on any new interest and forge new universes in your path.” I recall this experience as if it happened yesterday. Another GT legend was Tech librarian Dorothy Crosland. In 1968, after a classmate encouraged me to listen to Brahms’ Symphony No. 1, she helped me get the LP record. It started me on a course of loving classical music. She was instrumental in transforming Tech library into a genuine library science environment. She also played a major role in the emergence of Tech’s School of Information Systems. —Mel Bost, Phys 69, MS NE 70

Yellow Jacket Control-Line Plane

Editor, I thoroughly enjoyed the Fall 2025 issue of the GT Alumni Magazine. As a co-op in the early 1960s, I was involved with many military and NASA contracts, and just maybe had a small part in the Space Race. This brought back many memories. On page 98, the Yellow Jacket control-line airplane was featured. In the 1950s, and even through the early 1960s, I put in many hours building and piloting all types of miniature aircraft. To add to the article, these planes were constructed of varying grades and strengths of balsa wood and Sitka spruce. The structures were covered with a paper/cloth fabric called “Silkspan”; Mat Waites’ tea bag analogy was spot-on. We then painted the model with “dope,” which was a lacquer-type of paint that had an odor of dead-ripe bananas. The control-line airplanes only had an elevator, so the “steering” was either up or down. The engines were a single cylinder, most often with a displacement (combustion chamber) of less than ½ cubic inch. These engines used a fuel made of methyl alcohol, nitro-methane, and additives such as castor oil for lubrication. They were 2-cycle, and as the piston was on the upstroke, it would suck in the fuel/air mixture and compress it. The external battery did not provide heat; it merely passed a current through the glo-plug’s spiral nichrome wire to make it glow orange hot inside for the first few seconds during starting. Basically, these engines were sort of operated like a diesel, creating its own sustaining combustion heat via high compression. On the downstroke, the expanded hot gases would blow out through a port in the side of the cylinder as the new fuel in the chamber was at the same time pushed into the firing chamber. Polluting and inefficient, yes! They were built for simplicity, light weight, and power. —Robert Hoenes, EE 66

Tech’s Resident Glassblower

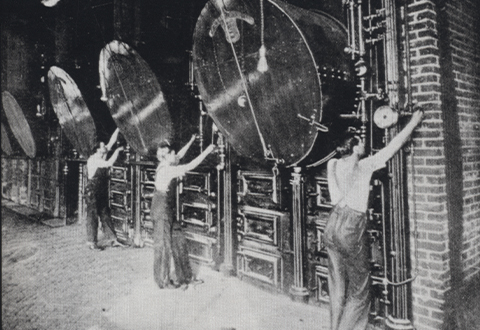

I read Don Lilly’s obituary in the Fall 2025 Alumni Magazine. From the day I walked in, I was more than impressed by the glass shop at Georgia Tech. Most chemistry students do their own glass work. D. Lilly was an outgoing and sarcastic sort of guy who told you how dumb you were while saving your life or career. I worked for E. C. Ashby organometallic chemistry. Don made numerous unique pieces of glassware required by Ashby’s group. We did chemistry that burst into flame or exploded in air (trimethylaluminum, etc.) and were required to keep everything in an inert atmosphere. I’m not sure we could have functioned without him. For me, his master work was a device for measuring viscosity of water/air-sensitive solutions like liquids via two capillaries inside a water jacket and entirely enclosed in an inert atmosphere. Students and post-docs tended to hang out in Don’s area when they weren’t working or killing time (waiting for a reaction to finish or a chromatogram to run). The glass shop was a unique feature at Georgia Tech that certainly gave our students an advantage over similar schools. We (Ashby) were in bitter rivalries with research groups around the world. —George E. Parris, PhD Chem 74